Yes to a Living City: Applying Jacobs' Principles to New York's Rezoning

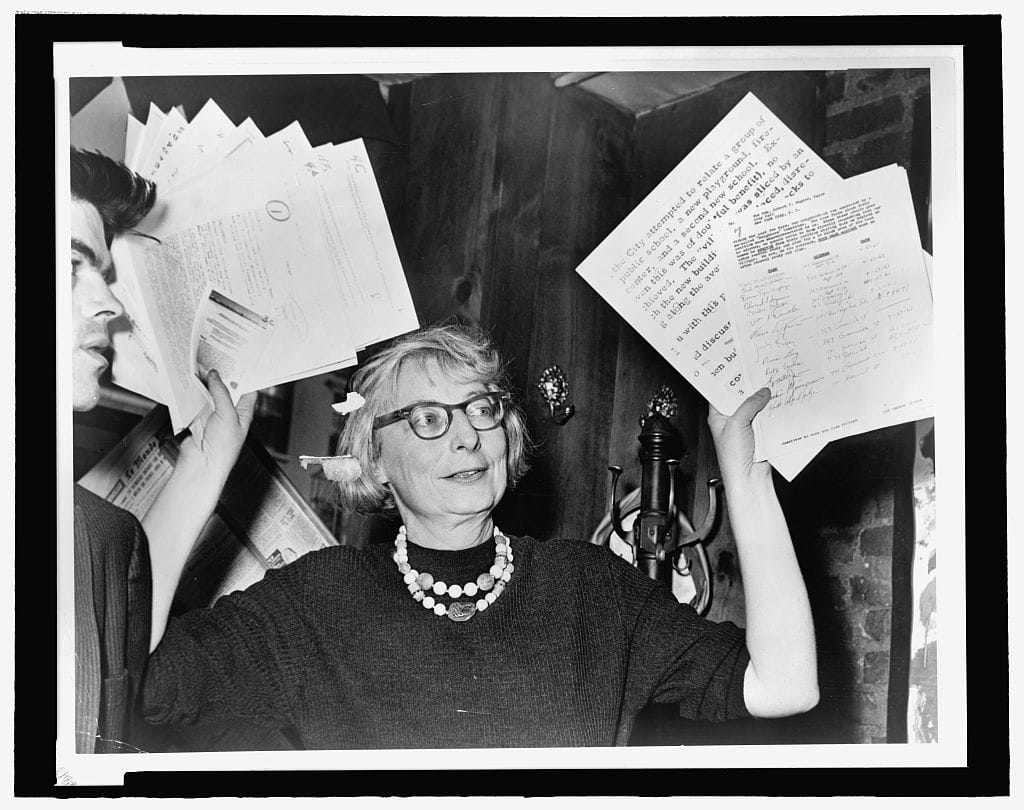

The urbanism of Jane Jacobs, then and now.

Later this year New York City's council will vote on the mayor's ambitious rezoning, the City of Yes. This change will reform the zoning code in numerous ways, including allowing for Accessory Dwelling Units, Single-Room Occupancies, infill housing, and by-right mixed-use buildings across the city.

These changes are a once-in-a-generation shift in the city's land-use, with the last major changes occurring in the 1960s. In 1961, the urbanist writer Jane Jacobs wrote The Life and Death of Great American Cities, where she laid out a number of problems in then-present urban planning.

Since it was published, we have seen the consequences of those planning policies. Today, it is time to re-evaluate what Jane Jacobs wrote and why the City of Yes is the right path forward.

Density versus overcrowding

Gentrification was a phenomenon Jacobs observed in the 1950s, although she did not give it that name. She noticed neighborhoods that were in the process of "unslumming" found an "increase in diversity of incomes" and an "increase in visitors".

Displacement is a growing issue in the city. Over 200,000 Black New Yorkers have left in recent decades for cheaper cities like Atlanta. As the vacancy rate approaches 1%, few people are able to find available housing. This has contributed to a growing homelessness problem.

Today, immigrant families have been pushed between shelters and tents on an airfield because the city has been unable to accommodate our current population nor build homes in anticipation of population growth.

The tenement homes were scorned by many politicians and urban planners in the last century, who were upset at the grime and noise. At the same time, they provided affordable housing and stability for many families who were trying to get a foothold in a new place. Jacobs writes the cheap tenement buildings were "built to house the flood of immigrants first from Ireland, then from Eastern Europe, and finally from Sicily." Restrictive zoning was implemented and pulled the ladder out from future immigrants trying to find affordable shelter.

She also noted improvements to communities over time with economic progress. In Boston’s North End neighborhood, rising prosperity allowed the community to make their own improvements without the interference of planners who thought they knew better what the community needed. In Streets of Gold, Princeton economist Leah Boustan writes that immigrants may struggle when they arrive but their children thrive.

"Overcrowding means too many people in a dwelling for the number of rooms it contains" notes Jacobs, who goes on to praise the development of high-rises as a means to expand housing opportunity. "Elevator apartments are today the most efficient way of packing dwellings on a given amount of building land" and continued to grow more efficient as crane technology improved and heights rose.

Yet to build tall can lead to an architectural monotony. "It is not easy to reconcile high densities with great variety in buildings, yet it must be attempted. Anti-city planning and zoning virtually prevent it."

Today, a number of regulations apply burdensome mandates on the architectural design of multifamily housing. For instance, requirements on double-corridor stairs in new multifamily units leads to bulky floor plans. New York state is seeking to reform this, and the annual budget asked the state's fire prevention and building code councils to make changes.

A greater supply of housing does not necessarily lead to sprawl. By concentrating housing in the city, nature is preserved. "Each day, several thousand more acres of our countryside are eaten by the bulldozers, covered by pavement, dotted with suburbanites who have killed the thing they thought they came to find".

Jacobs praises the urban design of architect Le Corbusier, whose vertical cities could house a large number of people, "but because of building up so high, 95 percent of the ground could remain open". This preserves city land for green space as well as preserving land outside the city. "The concentration of people must be heightened."

However, urban planning decisions can force sprawl to exist. For example, mandatory parking requirements have led many cities to dedicate large swaths of space to the storing of private vehicles for short periods of the day. When the cost of parking is free, it further encourages people to drive into city centers. This leads to congestion, air pollution, and less funding for public transit. The City of Yes aims to remove these mandates and allow each project to choose what makes sense for them.

During the period Jacobs wrote her book, Robert Moses was busy turning parts of New York City into highways. She pushed back against these efforts, eventually saving Washington Square Park from becoming a throughway. She viewed Moses as an adversary, saying "expressways that eviscerate great cities. This is not the rebuilding of cities. This is the sacking of cities". It was due to her efforts that the Lower Manhattan highway was canceled before it could bulldoze through the now beloved neighborhoods of SoHo and Chinatown.

Highways also contribute to sprawl, pushing homes and businesses farther from each other and requiring motorized transportation to get anywhere efficiently.

Limits to preservation

In the first half of the twentieth century, New York City was constantly in flux. Construction was common everywhere. More homes were constructed every year than today, not even considering per-capita.

A rush of developers bought up tenement buildings and pushed through "urban renewal" changes, displacing existing residents and erasing their legacies. During this period, people were not prioritized and neither were their communities. In Greenwich Village, the city was trying to "renew" the neighborhood "into an inane pseudosuburb".

For this reason, Jacobs encouraged legislation to encourage preservation over historical buildings and landmarks. At the same time, she warned against it being used too much to stop all development and cause exclusive neighborhoods. Today Greenwich Village is trendy, but with homes that are unaffordable to most city residents. Urbanism was preserved, but the community has stagnated.

The purpose of zoning for deliberate diversity should not be to freeze conditions and uses as they stand. That would be death. Rather, the point is to ensure that changes or replacements, as they do occur, cannot be overwhelmingly of one kind.

To Jacobs, a city was supposed to be about people first. She did not like the vast network of parks across the city, how they were "streets without eyes" and were "underused". She cared more about the city block, wanting a variety of small blocks, "the basic unit of city design". She is often cited for the concept of "eyes on the street", where a neighborhood is able to provide its own safety and security through populated blocks.

In her view, her preference for urban streets over manufactured parks was a key part of her philosophy. Urban planners in her view were faux progressives who were "unbuilding and oversimplying cities." She rejected the pastoralism of garden cities in favor of one that reflected the true messiness of humans.

A dynamic, thriving city

Although Jacobs promoted preservation, she never intended entire neighborhoods to become frozen in amber and protected from any sort of change. Rather, she encouraged new buildings. She considered neighborhoods "a failure" if they were "unable to support new construction".

She recognized that a city had to change, that "cities are an immense laboratory of trial and error, failure and success, in city building and city design." For those cities that became mired in NIMBYism, they "contain the seeds of their own destruction and little else. But lively, diverse, intense cities contain the seeds of their own regeneration, with energy enough to carry over for problems and needs outside themselves."

Her ideal city block promoted diversity at a structural level, observing the phenomenon of filtering: as structures including housing gets older, rents get cheaper compared to new buildings nearby. Through a gradual process, "some of the old buildings, year by year, are replaced by new ones--or rehabilitated".

The dancing school that becomes a pamphlet printer’s, the cobbler’s that becomes a church with lovingly painted windows—the stained glass of the poor—the butcher shop that becomes a restaurant: these are the kinds of minor changes forever occurring where city districts have vitality and are responsive to human needs.

A successful city is also about a diversity of people. Older tenants should not be displaced, but there also needs to be room for new tenants. Today, homes in LGBTQ+ friendly neighborhoods around the country are 50% more expensive. Our cities are failing in their mission to welcome people of all ages and backgrounds.

What makes a city successful is its ability to bring people together of different backgrounds, benefitting from agglomeration effects. "The diversity, of whatever kind, that is generated by cities rests on the fact that in cities so many people are so close together".

I recently went to a community board meeting for the City of Yes. Several attendees talked about their first years in the city, when they stayed in one of the remaining single-room occupancies to get them on their feet. Expanding and enabling the construction of these units would make the city more inclusive to those who need it the most.

In addition, new construction aids the city as a whole. "Redevelopment for private profit is ideologically and fiscally justified on the grounds that the public subsidy investment will be returned over a reasonable period in the form of increased taxes from improvement."

Jacobs was in favor of public housing projects like NYCHA. She recognized that "we need dwelling subsidies...for that part of the population which cannot be housed by private enterprise." To strengthen NYCHA campuses, the City of Yes is enabling them to redevelop underused land to fund repairs.

She was not against private investors. She recognized that "private investment shaped cities". To her, the private community was made up of individuals. Our "social ideas (and laws) shape private investment". Private developers could develop affordable housing if they had proper incentives. The City of Yes encourages developers to build more density through the universal affordability preference.

Today it is clear that more housing is necessary. Our crisis is deep and requires a significant shift in our thinking. We cannot squabble over minutia while tens of thousands wait in shelters and hundreds of thousands are on a housing waitlist. A shelter "is a useful good in itself, as shelter. When we try to justify good shelter instead on the pretentious grounds that it will work social or family miracles we fool ourselves."

We need to admit there is a limit to our ability to plan. Our zoning regulations have forced architecture into a place that's "sterile" and "regimented" which limits "spontaneous diversity". Laws mandating height limits and floor-area ratio caps created new standards that were not applied retroactively, such that "most of the streets affected already contain numerous buildings in excess of the new height limitations". By raising the FAR cap, dense communities can build a sufficient amount of housing

Jacobs believed the greatest fault in zoning laws "lies in the fact that they permit an entire area to be devoted to a single use". However, it isn't necessary to cause "some sudden, cataclysmic upheaval" in housing. Rather, "densities should be raised...gradually". The City of Yes introduces town square zoning in low-density neighborhoods to enable a few stories of housing to be constructed over commercial businesses.

Jane Jacobs moved to Toronto in 1968 and passed away in 2006, so I cannot say her exact thoughts on contemporary New York City zoning policy. Yet if we follow her writings, we can understand her views on what makes a city successful: density through tall buildings that aren’t overcrowded, urban blocks with a mix of old and new buildings, and a people-first approach that prioritizes housing.

She saw the problems with restrictive zoning and the vanity that the city could micromanage how everyone lives. Today we have the opportunity to reform our approach to building communities, from one that is resistant to change to a system that is organic and welcoming. The City of Yes, through its broad set of reforms, provides opportunities for people of all kinds to find a home here.