Why Movements Fail

Horizontalism and its discontents

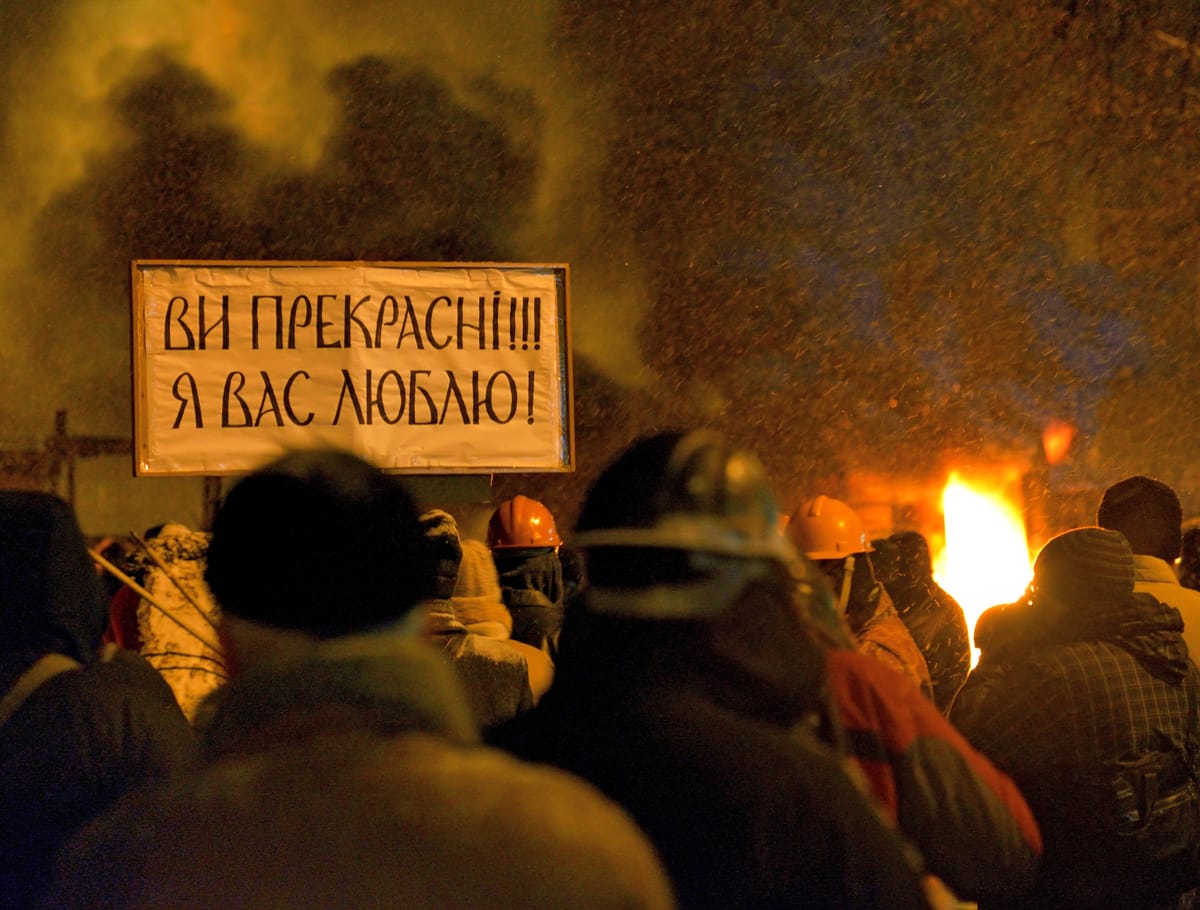

Vincent Bevins' If We Burn asks a simple question: why did the mass protest movements of 2010-2020 largely fail to achieve their objectives? Bevins is not referring to American protest movements—not the Women's March, not Black Lives Matter nor George Floyd, but rather to other protest movements around the world: the Arab Spring, the Hong Kong 2019 protests, Turkey's Gezi Park protests, the 2013 Brazil protests, Euromaidan, and still more besides. These protests mobilized and energized millions of people in each country to take to the streets and demand a better world. What they got instead was counterrevolution—Sisi, Bolsonaro, Poroshenko, the iron fist of the Communist Party closing down ever harder. Bevins' mournful book is an attempt to understand how this happened—and how we can do better next time.

Let's start with some of the basics of the major episodes. Going through the details of each would be impossible here; instead, consider Egypt and Brazil as paradigms.

In January 2011, these protests began as a reaction against the police brutality of longtime dictator Hosni Mubarak's regime. But riding the wave of the Arab Spring they quickly exploded in size, and demonstrators occupied Tahrir Square, a central square in Cairo. After weeks of conflict with the security forces, Hosni Mubarak stepped down in February, and the military agreed to an election. In June 2012, the liberal factions split the vote and the Muslim Brotherhood candidate Mohamed Morsi was elected president (94). After Morsi attempted to ram through an Islamist constitution, a second wave of protests broke out in June 2013. In July, Morsi was deposed by his own minister of defense, Fattah el-Sisi, who would go on to establish himself as military dictator in the Mubarak mold.

An eerily parallel series of events would play out in Brazil almost immediately afterwards. On June 6th, 2013, the Movimento Passe Livre (Free Fare Movement) began a series of actions intended to prevent a 20-cent rise in the municipal bus fare in São Paulo (116). To their surprise and delight, this kicked off a broad-ranging national protest movement which would pull millions of people across the country onto the streets and, by June 17, storm the halls of Brazil's parliament (132). The government would accede to MPL's demands on June 19 (136). But the protests would not stop. Left-wing President Dilma Roussef's popularity would crater, going from 57% prior to the protests to 30% afterwards (147). Her popularity would never recover, and she would be impeached in 2016, paving the way for the election of far-right radical Jair Bolsonaro in 2019.

Bevins extracts from these and a dizzying array of other worldwide protest movements a surprisingly common repertoire of contention:

- Occupying central squares of symbolic importance

Marches - Staged or natural symbolic moments for media consumption and reproduction

- Fighting with the police

- Property damage

- Blocking of roads and highways

Now reader this may all seem perfectly natural to you—"what else could a protest consist of?" But that is just a reflection of how embedded this specific repertoire is in our culture. Consider what it does not include:

- Targeted assassination

- Armed occupation of government buildings

- Mass murder

- Strikes

- Boycotts

- Writing letters

- Seizing the means of production

You'll instantly recognize that these tactics are more closely associated with other traditions of political action—whether that's right-wing, liberal, or classically Marxist—which should just highlight more clearly that the mass protests Bevins analyzes shared a distinctive repertoire of contention and were drawing on a distinctive theory of politics more broadly. So what was that theory?

Bevins calls it "horizontalism." The term comes from Argentina's 2001 protests (43), but the idea goes back much further—Bevins traces it to the New Left of 1968 (17). This movement—animated by the questions of civil rights and the war in Vietnam—was equally a reaction against prior leftist organizations. These organizations were "Leninist" in that they endorsed "democratic centralism"—the idea that the central party's views would be decided democratically, but once decided would be enforced hierarchically. In practice of course there was precious little democracy to be found in the Communist Parties of those years. The New Left saw these organizations as themselves autocracies in miniature, hierarchically organized, captured by the Soviet Union, and not different in kind from the other authoritarianisms they opposed. Hence: horizontalism. No leaders, no hierarchy. Each person individually free to assent or not, group decisions only made unanimously (and therefore typically after hours and hours of discussion). Horizontalists can have organizations—they just tend to be extremely small. Only a dedicated group of close friends and comrades can make every decision by consensus (25, 201-202). It's worth quoting influential theorist Marina Sitrin at some length here.

These movements emerged in response to a growing crisis, the heart of which is a lack of democracy. People do not feel represented by the governments that claim to speak in their name. The Occupy movements are not based on creating either a program or a political party that will put forward a plan for others to follow. Their purpose is not to determine “the” path that a particular country should take but to create the space for a conversation in which all can participate and in which all can determine together what the future should look like. At the same time, these movements are attempting to prefigure that future society in their present social relationships.

But horizontalism is at most a principle of organizing; a repertoire of contention is a set of tactics. What of goals—what of strategy? What theory of change ties together these components? There's one model lurking nearby that seems like it might be an answer: "we impose costs on the regime until they give us what we want." Call it coercive or extractive or concessionary or adversarial, the basic idea is simple enough. The trouble is that a horizontal leaderless organization would of necessity struggle to coordinate the kind of action necessary for this theory—and in practice very much did struggle to control the protests they unleashed. Only a disciplined, hierarchical organization has the capacity to turn protests on and off as a result of policy negotiations. This particular problem was on vivid display in several of these protest movements

Movimento Passe Livre (Free Fare Movement) initially launched a highly targeted campaign with a well-defined goal (to stop a proposed fare increase for São Paulo's public transit); similarly Euromaidan began with a small protest against President Viktor Yanukovych blocking the European Union–Ukraine Association Agreement. Both of these small groups touched off immensely larger protests, which they were totally unable to control.

But there's a deeper point here. These groups were not even interested in negotiating or accepting concession to their demands. To quote Sitrin again: "The fact that the movements do not have the conquest of the state as their goal does not mean they do not want countless things changed." In Brazil, even when city officials invited Movimento Passe Livre to negotiate with them over the state of public transit, they refused—and this points to the deeper issue (119).

None of these large-scale movements were interested in negotiations or concessions. The truth is that these protest movements were largely not operating with that theory of change. Rather, Bevins argues that they were operating with a teleological theory of change. Whether Whiggish or Marxist or Fukuyamist, teleological theories of history hold that history has a natural direction to it—and that that direction is a good one. As Bevins evocatively puts it, "Many people in my generation [] thought that if you simply gave the thing [history] a kick, it would come unstuck and move in the right direction" (259). This explains the oddly unspecified and open-ended nature of the repertoire of contention discussed above. Bevins' summary (258) is pithy:

1: Protests and crackdowns lead to favorable media (social and traditional) coverage

2: Media coverage leads more people to protest

3: Repeat, until almost everyone is protesting

4: ???

5: A better society

The idea was simply that these tactics will create disruption and more importantly create spectacle, the spectacle would create more protest and more disruption, and then the implacable structural forces of history would take over—no need for any Leninist vanguard party—and move society forward.

Bevins astutely notes the importance of modern media, social and otherwise, in this conception. Before photography, before newspapers, the idea that you could change a national government by having a big gathering in one city square would have seemed nonsensical. It is only in the capacity of these gatherings to be seen by millions around the country that they could possibly have the power supposed.

The funny thing is, this worked—sort of. These mass protests did unstick history, at least for a little while. The trouble is that history did not then automatically lurch into utopia. Rather, right-wing forces seized these moments and seized power—Sisi in Egypt, Bolsonaro in Brazil, Petro Poroshenko in Ukraine, Xi in Hong Kong. This is the fundamental horror that Bevins confronts—how did the Arab Spring go sour? How did this moment of tremendous hope and liberation and real power lead to—more of the same old men in charge of everything?

Bevins has an idea. As both Mayara Vivian (a leader in MPL) and Fernando Haddad (the once-mayor of São Paulo) both said to Bevins, "there is no such thing as a political vacuum" (263). Organized, violent right-wing forces—comfortable with hierarchy and violence—were willing and able to seize power. Meanwhile left-wing movements and leaders, consumed by horizontalist ideology, were unwilling to take power even when it was offered to them. The tactic of protest—>spectacle—>protest succeeded at mobilizing mass numbers of people, and it succeeded at creating the space for change. But it did not succeed at grasping the moment it had created. In one bizarre but illustrative example, the Brazilian protests became defined by the "Five Cause," issued by the hacker collective Anonymous (139). Except the "hacker collective" in question was just a guy who bought a Guy Fawkes mask, and the causes were just a grab-bag of different ideas he'd found on Facebook (146). Bevins quotes Cihan Tuğal's famous aphorism: "Those who cannot represent themselves will be represented" (143). Meaning can and will be imposed on mass protests no matter how chaotic and contradictory and leaderless they are.

So what is to be done? Here Bevins begins to run out of steam. He gestures vaguely towards revolutions that change the "real structure" of society. He waves his hands at "Leninist" organizing, an embrace of hierarchical organizations. But there's a problem with this. The decline of hierarchical associations is not some problem specific to the left, but rather an endemic feature of modern society. As Mancur Olson notes in his The Logic of Collective Action, organizations can only be hierarchical at all when they can selectively distribute some benefit (or punishment) to their members based on compliance with that hierarchy. (This is why, for instance, so many political parties have been tightly linked with political graft and patronage systems at one point or another.) Of course, this reward does not always need to be monetary—access to party organs like newspapers or printing presses was once central to nascent political organizations. Here again we see the central importance of social media to the modern political landscape: the barriers to entry for political "competition" have never been lower. Anyone can talk to everyone for the low cost of a free social media account.

We can see this exact dynamic at work in the stunning weakness of American political parties qua hierarchical organizations. Witness the Democratic Party's near-total inability to enforce ideological conformity on its own members—or the Republican Party establishment's total inability to stop the Trump takeover in 2015 (indeed, his takeover was so complete it's easy to forget that Jeb was their man).

It doesn't matter whether Lenin-style "democratic centralism" is desirable or undesirable: it is impossible. Try to enforce ideological conformity on dissenting members of your organization and they'll just go form their own new one. It's not like you can stop them.

So is horizontalism simply an inevitable result of structural forces? I think not. There's something deeper here, something that can easily go missing in these dry political-economic analyses of protest movements, yet which is nevertheless central to understanding them. Bevins brings it up repeatedly: the experience of protest. The experience of protest is easy to overlook or ignore or subsume to some other more familiar mode of human experience. But consider the language Bevins repeatedly turns to to describe it:

"It felt like something had shifted in the nature of time itself. They had cracked open the structure of reality. ... Everything was possible." (66)

"an escape from the alienation of everyday life" (113)

"deep, unmediated connection with another human being" (112)

"[She became] part of this giant, euphoric ball of people growing and pulsating and reshaping reality. Part of History." (249)

Protest is an ecstatic experience, in the properly religious sense: a bolt from the heavens that cleaves you from the shackles of mundanity and lets you see past what law and custom and power make "impossible" and touch the truth of a better world. In Fouche's evocative phrase, these ecstatic experiences allow you to "[hear] the Lord of Hosts marching through history and, in the footfalls of almighty God, [hear] that what was truly impossible has become intrinsically, if not readily, possible. What was available only in hypothetical rawness has become a real possibility that can be seized." The truth we moderns have forgotten is that ecstatic experience—religious experience—is a rare but very important mode of human consciousness.

But. This ecstatic experience is kind of like the blazing sword from a fairytale: powerful and essential, but dangerous to the soul. Power pretends to inevitability; ecstatic experience shatters the lie—and much of that power, in the process. But you can get addicted to the feeling, you can protest for protest's sake, without any further end. As one MPL activist would admit to Bevins, "the fight was the point," not the policy change it produced (286).

This underlies the allure of horizontalism. Horizontalism promises power without accountability, revolution without compromise. Give History a kick and it'll take care of the rest. "I'm not doing anything, it's the impersonal forces of history/the nation/class struggle." You can focus on that feeling you had out on the streets, everyone living and breathing and moving as one joyous whole—without ever having to have the moral courage to articulate what that better world would actually look like or how we might get there. Don't worry about the brutal comedown when the millennium once again fails to arrive, don't think about how reality will never match up to the dream because that's not a thing reality can do.

Horizontalism is not the solution to our problems. Horizontalism is a trap. And I want to emphasize rather strongly that this is not some academic point. As an unnamed Egyptian revolutionary puts it: "In New York or Paris, if you do a horizontal, leaderless, and post-ideological uprising, and it doesn't work out, you just get a media or academic career afterward. Out here in the real world, if a revolution fails, all your friends go to jail or end up dead" (270). We are therefore confronted with a critical problem: without either teleology or hierarchy to support progressive political movements, what can? A real answer to that question is beyond the scope of this essay. But I want to at least gesture towards one.

Bevins' scope prevents him from reflecting on Volodomyr Zelenskyy's election in Ukraine in 2019 and the country's decisive turn towards the West. In the long run, that small group of elites and intellectuals shivering in the Maidan Nezalezhnosti got precisely what they wanted—and they got it by persuading a large majority of the nation to agree with them. The man who sparked it all off, Mustafa Nayyem, is now the chief of the State Agency for Restoration and Infrastructure Development. Show up and be ready to rule. Show up with a pitch that persuades. Show up with a dream—but show up with an answer too.

Featured image is You are glorious. Euromaidan 2014 in Kyiv, by Ввласенко