Why (Almost) Everyone Can Endorse a Liberal Framework

Even most liberal-skeptical radicals have good reason to endorse a basic liberal framework.

Many historical and contemporary liberal views argue that coercive political and legal institutions should face a high burden of justification. Because of a presumption in favor of individual liberty, these institutions should not be mechanisms for imposing sectarian views about how the social and political world ought to be for everyone. Rather, they should reflect what (almost) everyone has reason to endorse, whatever their other normative commitments. These include: securing conditions for peaceful interaction, dispute resolution (e.g., conflicts over competing property rights claims), finding coordination points (e.g, contractual boilerplate or traffic regulations), and providing social resources adequate for being recognized as a free and equal member of moral communities. These institutions comprise what I will call a “liberal framework” tasked with protecting basic rights and freedoms such as conscience, association, and property.

Some will view even these functions as controversial. An anarcho-communist may bristle at property claims beyond personal belongings or use rights, while an anarcho-capitalist will not find much favor in redistribution to secure a social minimum. In response, one could make a case for excluding their membership in a liberal polity, or argue that they really are committed to what they claim to deny. But little is ever uncontroversial in political philosophy. The question isn’t “What regime or set of policies is beyond question?” but “What is less controversial compared to available alternatives?” I suggest here that a liberal framework is controversial but less so than alternatives.

Functions falling outside the above areas are more controversial, often more burdensome to ensure compliance, and thus harder to justify. This results in what political philosopher Jerry Gaus called liberalism’s “classical tilt.” Some regard a more extensive regime as ideal, but they can’t insist that those who differ go along. For these “expansionists” a smaller regime is still preferable to failing to agree on a set of rules for living together.

Likewise, the abovementioned anarchists should regard a liberal framework as preferable to Hobbesian or Lockean states of nature. Freedom of association could better allow anarcho-communists to organize worker syndicates than in a state of nature with no guaranteed associational freedom, although market pressures might not allow syndicalist arrangements to be competitive (see Robert Nozick's Anarchy, State, and Utopia). Freedom of association could also better allow anarcho-capitalist experiments without income or capital gains taxation, or coercive redistribution. The “anarcho-” of either system implies that people should voluntarily gravitate toward either arrangement, and the best way to ensure voluntariness is by not preventing people’s freedom to try.

The above suggests a liberal framework is justified largely by ruling out more extensive regimes ordered around a sectarian vision about how the world ought to be and why each member must help bring those aims to fruition. This may disappoint some readers. Is that all that can be dreamt of in our (political) philosophy? Even if skeptics concede what I’ve claimed so far, why should we think a mere framework warrants our allegiance? Who would give their life for a mere framework? I will briefly discuss this and other objections to liberalism.

Objection: Liberalism is morally bankrupt. Liberalism is sometimes equated with worship of license or maximal choice. It is said to give no ethical counsel and endorses greed and hyper-individualism, unbound from community or tradition. In defending the sanctity of individuals, liberal values end up glorifying the self and the almighty dollar, to the detriment of strong social ties or a sense of duty to one’s community. Corporations profit on the backs of their employees, elderly and infirm people die alone in nursing homes, unmoored children self-medicate or immerse themselves in polarizing social media instead of meaningful pursuits. Everything is commodified and transactional, even what should be based on relationships and care. In short, we tried liberalism and it failed us.

Blaming liberalism for these pathologies is like blaming the Big Bang for them. They may exist, but saying they exist because of liberalism, and would not be as likely to occur otherwise, requires argument beyond asserting correlations. Aside from attacking a straw man, this objection mistakes a part for the whole. Liberals need not take a political stance on what conception of the good all individuals should pursue or what substantive ethical codes they should follow because taking a stance is neither necessary nor desirable. It’s not necessary because the core moral justifications for a liberal framework, such as respect for basic rights, are widely shared and “thin.” They guide our interactions whatever else we may believe or do. It’s not desirable because coercion based on sectarian commitments is often what we’re hoping to avoid in the first place when evaluating political regimes. Even non-liberals can recognize the need to accommodate pluralism.

As a framework, liberalism is better understood to allow pursuit of diverse ethical codes and ways of life, including those that are themselves non-liberal in the sense of not valuing individual freedom highly. A society composed entirely of ascetic monks, assuming it could endure, is consistent with a liberal framework provided the monks aren’t coerced into keeping that way of life.

Everyone should have the choice to accept/reject/revise/maintain their various conceptions, but these are not matters to be maximized as some overarching social goal shared by everyone. Critics err in thinking liberalism promotes anything, including this or that conception of freedom. Frameworks themselves don’t promote; instead, they allow each participant to promote values and ways of life according to their conscience, compossible with others’ freedom of conscience.

Perhaps critics are making an empirical rather than normative point. They may grant that liberalism need not champion hyperindividualism and materialism, but its key protection of private property rights leads almost inexorably to moral degradation and social ills. This is an interesting claim, one that can be tested by running experiments in the lab and the real world. That segues to the next objection.

Objection: A mere framework enables experimentation that disrupts vital institutions and destabilizes society. A liberal framework would allow more widespread experimentation among a variety of matters (e.g., private and social entrepreneurship, novel forms of local participatory democracy, diverse markets, and civil societies) than we currently see in our mixed liberal polity. The results will be dynamic, perhaps even chaotic on the margins. Some likely positive upshots of such dynamism are discovery and replication of prosocial norms and massive economic growth.

This objection assumes that dynamism is anathema to stability while stasis prevents instability. Liberal frameworks with lots of experimentation can be somewhat stable through the robustness of diverse and overlapping social forms commanding various allegiances. Many types of alternative family structures can provide loving homes and a sense of lasting identity and cohesion for their members that would not otherwise be found in more traditional and homogeneous societies. Non-establishment of religion allows many types of denominations and churches to flourish. Radical changes won’t tend to happen all at once, or society-wide, since experiments will run through the diverse choices of many individuals and groups in response to feedback. Either way, we can simply test these claims by running the experiments and seeing what happens.

On the other hand, diversity doesn’t begin and end with liberalism. There are arguably more varieties of non-liberal views than liberal ones. Establishing some sectarian viewpoint as the dominant one will likely impose on a great many people, including communitarians who don’t subscribe to this or that particular view. That’s not a recipe for stability, at least not the kind worth having. Ironically, another problem with ordering a whole society around some particular conception of the good is that it’s very likely that one’s own preferred conception—liberal or otherwise—will be quashed too, and far worse than any resistance or erosion it risks within a liberal framework.

Still, critics may contend that liberals paper over the very imperfect ways liberalism has actually been realized.

Objection: Defenders of liberal frameworks excuse a deeply unjust status quo. The past two centuries may have witnessed a “hockey stick” of exponential economic growth and some progress on equal rights, but we also still see racism, corrupt and oppressive criminal justice, intellectual property abuse, a military-industrial complex, nuclear proliferation, crony capitalism, indigenous cultures wrecked by globalization, anthropogenic environmental crises, uncertainty about artificial intelligence, and inequalities entrenched by perverse norms or a rigged system.

These problems may exist because the institutions of the last two centuries, while holding many liberal features (e.g., rule of law, stable property rights, relative lack of barriers to entry), do not fully realize the liberal framework. Can we disentangle the good from the bad, attributing the bad to departures from liberal values and institutions, not instantiations of them? Detractors may call anything they don’t like “capitalism” or “neoliberalism,” but do they have a point about blaming some hard-to-avoid aspect of liberalism for social ills? Is it a mistake to respond that the above pathologies would not exist, or would be far less extensive, under the “true” liberalism that we’ve only approximated at various times and places? Or is this a copout, akin to saying the horrors of communism weren’t “true” socialism?

It would be humbling to discover the economic growth of the last 200 years was necessarily (or even accidentally) due to systematic oppression. Wealth, the accusation goes, was created in unprecedented levels not despite massive injustices, but because of them. No other realistic paths to such wealth creation exist except by widespread injustice. If true, then liberalism itself should cast a dim view on the wealth whose very creation violates the rights of many for the benefit of relatively few. Detractors can agree that the world is not zero-sum while insisting that it’s much less positive-sum than most liberals claim.

Does liberalism also need this ill-gotten wealth to sustain its rosy picture of universal freedom? If we could avoid oppression while peacefully maintaining preindustrial wealth levels, what would that imply for liberal rights? Some critics of liberalism might claim we never should have left our tribal past. The problem with this view is that oppression is the norm of recorded human history; it didn’t begin with the Industrial Revolution, and so it’s unclear how making resources much scarcer than they currently are would decrease injustice. Perhaps critics would respond that it’s too late to go back. The damage is done, and what we need is a post-liberalism that somehow navigates all the problems liberal capitalism created without introducing its own forms of oppression.

This underscores the need for empirical scholarship. Then the test of someone’s normative commitments is where they would stand if the empirics played out differently. If “wealth creation means oppression” should make liberals decry the mechanisms of economic growth, then these critics of liberalism have pro tanto, if not decisive, reason to be similarly open to revising their criticisms if it is shown that wealth creation does not require oppressive mechanisms.

Some historians claim they aren’t interested in exploring counterfactuals, only telling the story as it actually happened. That’s fine, but neglecting counterfactuals makes it hard to tell a causal story about norms, certainly a causal story that involves necessity or explanations of how liberal institutions may contain the seeds of their self-correction. Whatever injustices actually happened under liberalism’s watch, perhaps we best understand justice as a trajectory toward fewer and fewer injustices, not a perfectly realized end state or ex ante condition.

Suppose, however, that liberalism can withstand these objections. Liberalism then may become a victim of its own success. Liberal institutions may have helped usher in historically high levels of human progress overall—but what have they done for us lately?

Objection: Liberal frameworks cannot inspire the kinds of commitments many non-liberal ideologies can. One doesn’t have to believe wealth implies oppression to raise this objection. One may simply feel frustrated that a liberal framework can’t guarantee some specific utopic vision. “Have these institutions in place and people will likely make good things happen” doesn’t make an appealing narrative, especially in a world of abiding injustice.

Humans are drawn to narratives, however, so they often find stories compelling when they reduce the world’s problems to simple causes with clear good and evil sides. Take one radical view some have found inspiring: abolishing private property rights in the name of ending injustice toward workers and the poor.

Most socialists do not go as far as advocating total abolition of private property, but focusing on a boundary case of abolition can be instructive. Property abolition is neat and simple in alleging a deeply rooted problem and calls on us to act together to end this problem, ushering in a golden era free of market-led oppression. But inspiration divorced from reality is not a virtue, especially if the resulting passions in true believers translate to calls for widespread coercive dismantling or violent overthrow of the imperfectly liberal framework we currently have.

Even those who don’t think of themselves as liberals should reject property abolition as a solution. Well-formulated property rights are necessary (though not sufficient) for a liberal framework that protects other basic rights. In a nutshell: freedom of conscience isn’t worth much without freedom to act on one’s conscience, and one needs jurisdiction over resources in order to act on what one believes, without requiring permission from those who may oppose one’s views or actions. Without sufficient jurisdiction in the form of property rights, one’s freedom of conscience is jeopardized because one always requires permission from some authority to act.

This is not to say that our current scheme of property rights is acceptable in all its forms and consequences. Liberals should embrace reforms that might mitigate, if not eliminate, injustice. Corporations may have too much power to act outside the law or write their own laws. Banks unfairly profit when times are good but receive taxpayer bailouts during financial crises. States and multinational corporations take advantage of poorly formulated property regimes to exploit the lives and take the resources of indigenous peoples, often causing massive environmental damage in the process. Debt finance helps fund wars and the military-industrial complex while raising inflation rates.

None of these matters follows from a justification of property rights that both liberals and non-liberals can endorse as needed for living one’s life as one sees fit. Indeed, these matters are contrary to the values motivating that justification because they diminish people’s ability to live according to their own values.

Some of the disconnect may be that many liberals look at the status quo and tend to emphasize its good points while hand-waving at extant injustices, whereas critics tend to focus on the injustices while downplaying successes. Critics accuse liberals of perpetuating the status quo, liberals accuse critics of wanting to burn it to the ground, and what gets lost amid the finger-pointing are ample reform opportunities that both sides can endorse.

Reminding ourselves of a liberal framework and the basic freedoms it protects can help keep us anchored on the social values and rules (almost) all of us share, even as we differ on priorities or how best to implement these values. That should be plenty to inspire our commitment.

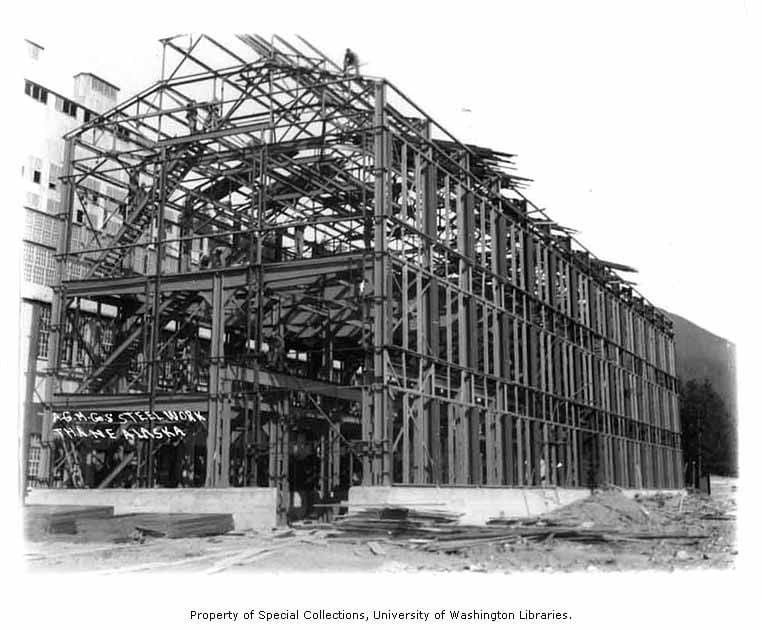

Featured image is Steel frame building under construction at Alaska Gastineau Mining Company mill