What Does “Defending the Constitution” Really Mean?

Does the oath of office I swore as an attorney for the trial court permit or even require me to defend the Constitution by force, if it is threatened by an illegitimate and authoritarian government?

Seventeen years ago, I sat in a nondescript basement office with Sharon from personnel, filling out paperwork for my new job as an attorney for the trial court. Sharon turned to me and told me I needed to take the oath of office.

Startled, I raised my hand and repeated the solemn words.

I swore to support and defend the Constitutions of the United States and California against all enemies, foreign and domestic, and to bear true faith and allegiance to those documents, in words prescribed by the California Constitution. (Cal. Const. art. XX, § 3.) A second paragraph of the California oath referring to advocating the overthrow of the government by force or violence or other unlawful means was omitted, because it had been found to impermissibly infringe on the First Amendment. (Vogel v. Los Angeles Cnty., 68 Cal. 2d 18, 26, 434 P.2d 961, 964 (1967).)

The oath I took in 2008 began to carry new weight after the 2024 elections and their aftermath. Did the oath I swore require me to do anything outside the parameters of my employment? Was I required to defend the Constitution with my words, my time, my money, or even my life?

A little research revealed that the US Supreme Court had considered this question in Cole v. Richardson, 405 U.S. 676, 92 S. Ct. 1332, 31 L. Ed. 2d 593 (1972). In Cole, a prospective Massachusetts state employee refused to take the oath of office, contending it was unconstitutional. The Court upheld the oath, concluding that it did not compel the oath taker to meet force with force, but only to commit to abide by our constitutional system, to commit not to use illegal and constitutionally unprotected force to change it. (Cole, at 684.) The oath did not intend to impose obligations of specific, positive action on oath takers. (Cole, at 684-685.)

Cole tells me that should the current constitutional system break down significantly or completely, I could continue to go about my day so long as I was not directly caught up in any constitutional conflicts. I practiced family law. The odds were that I would not be.

But in a constitutional collapse, would my oath prohibit my use of positive action in defense of the Constitutions up to and including force? Disregarding that the penalty for violating the oath is a charge of perjury, I found support for the idea that it would not.

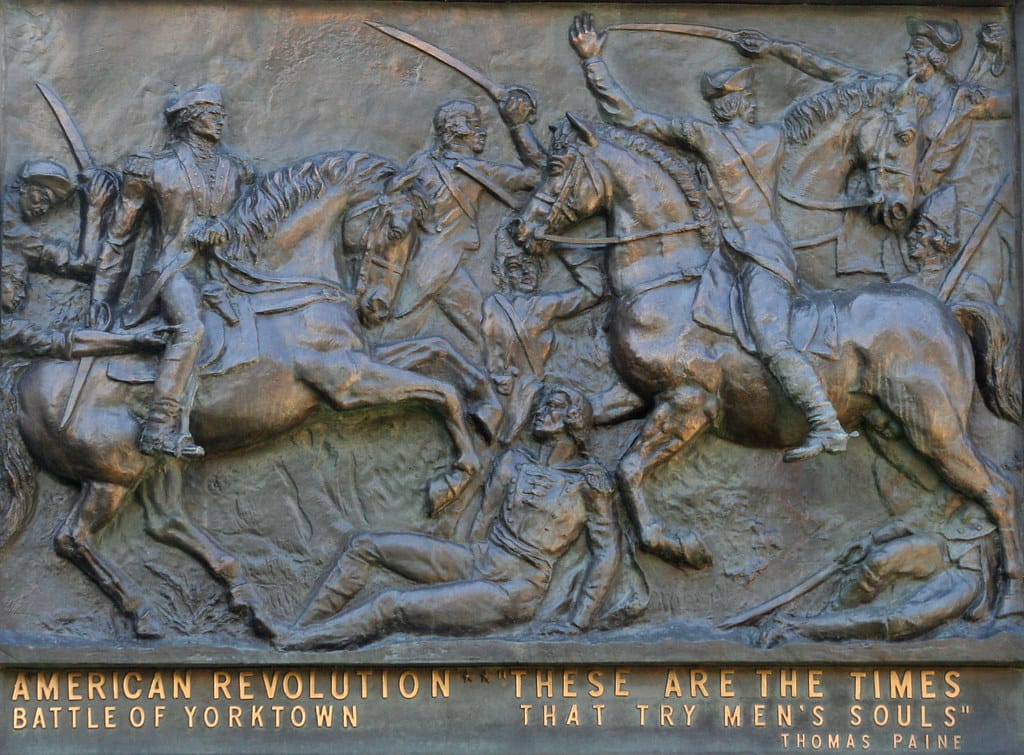

In a fascinating law review article published in 1983, the illustrious Jordan J. Paust argued that in some situations, private violence may indeed be lawful. Paust cited Justice Jackson, who wrote that, “… our own Government originated in revolution and is legitimate only if overthrow by force may sometimes be justified,” citing Am. Commc'ns Ass'n, C.I.O., v. Douds, 339 U.S. 382, 439, 70 S. Ct. 674, 704, 94 L. Ed. 925 (1950).

Paust opens the article with a quote from Abraham Lincoln’s First Inaugural Address:

This country, with its institutions, belongs to the people who inhabit it. Whenever they shall grow weary of the existing government, they can exercise their constitutional right of amending, or their revolutionary right to dismember or overthrow it.

From there, Paust argues that it is a fundamental democratic precept that authority comes ultimately from the people of the United States, and that with this authority there is retained a revolutionary “right to dismember or overthrow” any governmental institution that is unresponsive to the needs and wishes of the people. Thomas Paine, Madison and Jefferson, John Quincy Adams, and James Wilson all agreed that the source of all constitutional power is the people, and this view has been consistently recognized by the Supreme Court.

Paust points out that under that framework, the state does not have a monopoly on permissible violence. If revolutionary violence is carried out by the majority of the people, or with their general approval, it would be the government that lacked authority, and government controls of such violence or incitements to violence would be impermissible.

Paust then turned to the problem of armed revolution against those originally elevated within the legitimate structure of federal power, sometimes referred to as a self-coup or autocoup. Paust uses a disturbing hypothetical to illustrate the problem:

Suppose, for example, that after the House Judiciary Committee made its public declaration that Richard Nixon's conduct while in office warranted impeachment, trial, and removal from office, the President declared martial law, having obtained approval for such a measure from certain high-level military officers in the Pentagon. Assume also that after the declaration of martial law, numerous types of public protest of the measures of control implemented under martial law occurred in various places around the country leading, in some cases, to acts of violence and counter-violence, the jailing of dissenters, the closing of some newspapers and radio and television stations, and even the “disappearance”' of certain political leaders, professors, and students. Yet, as opposition continued beyond the first week, there occurred a breakdown of Pentagonian control of the military and whole units of the armed forces sided with other groups who were actively opposing martial law and demanding the overthrow of “Richard the President”' and of those who supported his “unlawful”' seizure of power. (footnotes omitted.)

Paust concludes that so long as the overthrow of “Richard the President”' had the approval of the majority of the people of the United States, then the movement could be legitimate.

Paust acknowledged the challenge implicit in such a movement: individuals would not know until later whether their efforts were permissible. Paust responded that it is not beyond the courts or decision makers to determine the legality after the fact. Paust also acknowledged that the difficulty in the moment could be exacerbated because the conditions of martial law may make it hard to know the views of most citizens. Today, this not knowing may spring from fear of surveillance and retaliation, even short of martial law.

The remainder of the article discusses the parameters for measuring legality of these actions in light of international law. For example, the right to revolution could not be used by a minority in an effort to oppress the majority, which effort could violate human rights “…but also constitutes a treason against humanity.”

Paust refers to the philosopher Herbert Marcuse’s framework for evaluating the ethics of a potential revolution. On the one hand, the individual would weigh various factors such as the sacrifices of living and dead generations made in defense of the established order and the intellectual and material resources available to the society and how they are used in satisfying vital human needs. On the other hand, the individual would have to weigh the chances of the revolutionary movement improving conditions and its ability to reduce the sacrifices and the number of victims.

This calculus is further proscribed by the means of revolution. Certain forms of violence and suppression can never be justified, such as arbitrary violence, cruelty, indiscriminate terror, or use of violence against certain targets. There are also principles of necessity and proportionality.

The revolution advocated by some on the far right would not pass these tests. First, the goal of that movement, which has apparently influenced the current administration, is to deny equal treatment or access to government resources for some persons, such as transgender individuals. The far-right-influenced means of seizing power are also impermissible, due to the violence, cruelty and indiscriminate terror already being used by ICE and the mass firings of federal workers, often without any notice.

Right now, it is unlikely that a majority of the population of the United States would support “dismembering or overthrowing” the current order, and of course nonviolent means would be far preferable. But if that time comes, my participation in a revolution would not necessarily violate my oath of office, especially if the movement were intended to restore the former constitutional system or to create a better, more responsive one.

What kind of sturdier system should be installed is a question for another day, but an admirable goal is set out in the preamble of our current governing document, “… to form a more perfect Union…” than the one that has led us here.

Featured image is Veterans of Foreign Wars Building on Capitol Hill, by David King