Two Paths to Immortality: Some Civic Religion for Nonbelievers

Reactionary immortality projects explain a lot about American political culture—above all why and how we Americans choose to panic.

As a western Buddhist, I’m often asked: “Do you really believe in reincarnation? Like, after you die, do you think you’ll be something else?”

Do I believe it? As a Buddhist, I seek to escape it. I’ve given rebirth a lot of thought, and I think almost everyone puts their hopes in some kind of afterlife, even if they wouldn’t call it that.

The major Christian creeds all profess the resurrection of the dead and the life of the world to come. And even most atheists believe in rebirth, after a fashion.

That’s because even most atheists usually have what anthropologist Ernest Becker called immortality projects. An immortality project is a set of commitments that you take on because you know that your physical body is going to die, and you’re trying, in some sense, to escape it. In The Denial of Death, Becker argued that the fear of death motivates a wide range of human behaviors, from the obvious to the bizarre.

A successful immortality project would make you a causa-sui—a self-causing Self—a being that escapes bodily death by creating itself anew. How grand that would be.

The ways we respond to our impending deaths form a thread running through every individual’s life. They range from the mundane to the galaxy-brained—from checking that the stove’s off to sending messages to extraterrestrials.

Some of these may be trivial, but some of them are the most psychologically important, meaningful, and tightly held plans that we will ever make. Immortality projects stand apart; they propose not just to ward off death for a time, but to transcend it, to make death completely irrelevant. Immortality projects are religious, in ways that I’ll explain in more detail below. They’re often political too, because they recommend specific programs for social action.

Immortality projects form a deep part of our civic religion, whether we realize it or not. Even if you don’t believe in literal immortality, it’s possible to be good or bad at pursuing the deathless. Immortality projects are rooted in a primal fear, and fear doesn’t always bring out the best in us. Certain reactionary immortality projects explain a lot about American political culture—above all why and how we Americans choose to panic.

Immortality, meet modernity

We’ve all heard of radical life extension. It’s a completely literal, 100% physical, this-worldly immortality project. I might say it’s not even original. Radical life extension is a lot like Christianity—it’s just a regimen for the body instead of the soul: Perform these acts on your person. If you do them right, you’ll live happily and forever.

“I don’t need eternal life,” a Franciscan friar once told me. “God’s already given me that.” Bryan Johnson, take note. For everyone else: I hope Johnson defeats death for many years to come, but he won’t defeat capital-D Death in the long term. In the long term, Death is just Entropy, and there’s no escaping that.

Less-literal immortality projects may put your hope for rebirth in some other phenomenon, so when your mortal body dies, you’ll live on without it. Shakespeare wrote his sonnets with his own death very much in mind, and he told his readers about how he would escape it:

But be contented when that fell arrest

Without all bail shall carry me away,

My life hath in this line some interest,

Which for memorial still with thee shall stay.

When thou reviewest this, thou dost review

The very part was consecrate to thee.

The earth can have but earth, which is his due;

My spirit is thine, the better part of me.

So then thou hast but lost the dregs of life,

The prey of worms, my body being dead,

The coward conquest of a wretch’s knife,

Too base of thee to be rememberèd.

The worth of that is that which it contains,

And that is this, and this with thee remains.

It used to be that an open, organized, creedal religious faith served as most people’s immortality project. Christianity denies death. It tells you right up front that you’re an immortal being; the only question is where you’ll end up in the next life.

By denying death, and by working for a good afterlife, traditional Christians could face the absurdity of a life that must end. Their faith in the next life gave their earthly lives a narrative coherence—and when they did think of death, they were reminded that it was a passage to Heaven.

Traditional Christianity could also structure a communal life. It invented whole new kinds of community, and it unleashed a torrent of great art and literature dedicated to its patrons’ immortality projects. It could make great crimes, too. There’s a tremendous unruly energy in joining a plan that’s so much larger than yourself. As Becker put it:

Man’s best efforts seem utterly fallible without appeal to something higher for justification, some conceptual support for the meaning of one’s life from a transcendental dimension of some kind. As this belief has to absorb man’s basic terror, it cannot be merely abstract but must be rooted in the emotions, in an inner feeling that one is secure in something stronger, larger, more important than one’s own strength and life.

And:

This is the most remarkable achievement of the Christian world picture: that it could take slaves, cripples, imbeciles, the simple and the mighty, and make them all secure heroes, simply by taking a step back from the world into another dimension of things, the dimension called heaven.

That’s what any mysticism seeks to do—to view life from the standpoint of the eternal, and in so doing, to give dignity to lives down here. I don’t personally find Christianity compelling, and scientific rationalists may have even harder words, but it worked. People gave their earthly lives to it, happily, and often well.

Modernity, though, has made a good immortality project a lot harder to find. Science has filled in a lot of the uncertainty that religion used to soothe, and religion’s miracles now seem doubtful. Now that God is dead, religious immortality projects may look foolish, not to everyone, but at least to many. The believers have started to go their separate ways. New mysticisms have emerged.

Really, I think there are only two culturally viable paths to immortality in the disenchanted modern world. I think when we try for immortality, we’re almost always on one or the other.

The path of blood

Genes have many of the trappings of a causa-sui. Genes make new life, including making copies of themselves. Genes live much longer than humans. The theory of evolution even had a hand in killing God—that’s some power!—so maybe we should put our hopes in evolution and the future of the species.

These thoughts seem to come naturally to a lot of us in the age of Darwin and Nietzsche. And they blend almost seamlessly with older ideas about bloodlines, founding fathers, dynastic politics, and the destinies of nation-states.

It’s a cliche to hope that our children will live on after us, and that their lives will, in a sense, be a continuation of our own. We can raise them in our values and sculpt them in our image. They’ll take to it naturally because they already carry some of our genetic code. And thus they become an escape from death itself: The man is dead, long live the bloodline. Becker again: “Nature conquers death not by creating eternal organisms but by making it possible for ephemeral ones to procreate.”

Even our procreation is only temporary, though, and our children are under threat as well. For the bloodline to last, it must find its own immortality project in a larger structure of allegiance—like a nation, a state, or a race. Each of these may also look a lot like a self-perpetuating self, a causa-sui. If you love your family, then surely you must love your race, of which it is a part. Even if your bloodline fails, your race will in a sense perpetuate it.

Now, all of that’s completely false biologically, but it has a social power anyway, because lots of people believe in it. Consider the Fourteen Words: We must secure the existence of our people and a future for white children. And why? Because that’s where certain racists have put their hopes for rebirth.

That’s their immortality project: They would make the white race the thing “stronger, larger, more important than one’s own strength and life,” in Becker’s words. Racists aren’t afraid of the racial other’s mere presence. No, they’re afraid that their immortality project is in danger.

This is psychologically deeper than skin-hatred, but it’s somehow much, much stupider. We have always been a racially mixed society. Your immortality project was never possible, not for a moment. Look your own death squarely in the eye—the death that you’ve identified with uncontrolled social change. Society will change; it always has. And people die; they always have. We’re all trying to navigate that the best we can. It’s no help to scapegoat others.

Even if you’re not openly racist, the path of blood is still tempting. You can still put your hopes in your bloodline, and from there, you can put your further hopes in the nation and the nation-state. Even in antiquity, Aristotle knew very well that the city could outlive the death of every single one of its inhabitants, and it would still remain the city: To live forever, like a city does, put your life into the city.

In modern times, Hegel championed this idea like few others have done. To Hegel, the state was the device through which we individuals realize all of our individual plans. The spirit of History moved through states, which Hegel called the march of God on earth. And there’s an immortal, a causa-sui to join with—the state.

Now, the state was in this game long before Hegel wrote down the rules. It expects most of us to bear children. It knows that we’re worried about our own mortality, and that our children are often immortality projects. The state knows that we can ease our fears of death by merging with something larger than ourselves, something that will tell us, at the very end of our lives, that it wasn’t all in vain.

The state, though, is also threatened. It seeks to defend itself, and as it does, it promises to defend its subjects’ immortality projects, even if it must resort to war: When we die for the state, it helps us to live forever, in a way.

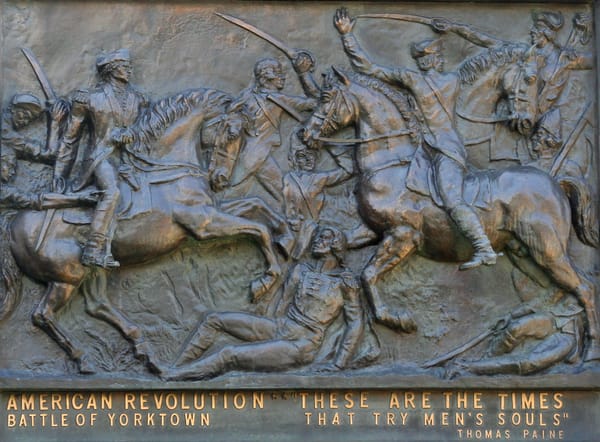

No, really. That’s the pitch. Even before Aristotle, polities took great care to keep the memory of Achilles alive. The fallen soldier’s immortality project lies not with his children, but with his immortal glory. Achilles will live on, to teach us that dying heroically means living forever.

Now, I hate to sound like a killjoy, but heroism as an immortality project was a lot more convincing when it only took a few evenings to tell the deeds of the fallen heroes. The immortality project called heroism struggles in the face of industrial warfare. There are just too many dead. The mind can’t hold them all.

That’s why the conclusion of Thomas Mann’s The Magic Mountain is so evocative. The novel’s hero, Hans Castorp, had tuberculosis, then a fatal disease. He’d been fighting it with the best medicine of the time, and he’d been doing much better—and then came the call of heroism. When the novel ends, he may or may not be properly cured, but he’s definitely fighting in World War I:

Farewell, Hans Castorp… Your story is over. We have told it to its end… Your chances are not good. The wicked dance in which you are caught up will last many a little sinful year yet, and we would not wager much that you will come out whole. To be honest, we are not really bothered about leaving the question open… And out of this worldwide festival of death, this ugly rutting fever that inflames the rainy evening sky all around—will love someday rise up out of this, too?

Hans Castorp’s bloodline will probably die with him, but we’re never told one way or the other; he just disappears into the silence at the end of the book. Mann saw the madness and futility of the path of blood, and he wanted us to see it too.

The state, at its origin, was a farm for conscripts, and it was perpetually at war with other farms that were doing more or less the same thing. The warrior state got its conscripts by organizing our immortality projects—genetic or heroic—so that, driven by our fear of death, we would serve the state’s ends, and not our own fearless interests. The state kills us, and sometimes it sings our praises. It uses our fear of death—our universal desire for immortality—to put us through a meat grinder.

The state that fights a war suggests you soothe your fear of death by dying for its sake.

It’s also hoping you can fuck.

An interlude about us queers

Non-procreative queer people—that is, people like me—can’t so easily follow the path of blood. We end bloodlines. As the queer low-fi rocker Car Seat Headrest put it:

Society wants me to fuck, well fuck 'em

Car Seat is a genetic stop sign

I sleep lying next to a mirror

Car Seat is a menace to the public

Love is a way of advancing our species

Love is because we want to keep up our species

Which makes Becker sound clunky when he’s saying the same thing:

Society wants to be the one to decide how people are to transcend death; it will tolerate the causa-sui project only if it fits into the standard social project. Otherwise there is the alarm of “Anarchy!” This is one of the reasons for bigotry and censorship of all kinds over personal morality: people fear that the standard morality will be undermined—another way of saying that they fear they will no longer be able to control life and death.

I too sleep lying next to a mirror. And they are so afraid of us. Under our influence, your very own child could be murdering your immortality project. With pronouns.

The anxiety doesn’t stop there, either. What about your kids’ kids? And what about the rest of the kids, right on down the genetic line, and all across the nation-state? If even one of them is non-procreative, someone’s immortality project is dead. Pretty soon we’ll run out of warriors, or people.

The fear of a botched immortality project explains everything about how cishet people stigmatize queer people. It’s a stigma that hits close to home; every queer person I know can tell you a story about disappointed relatives, who so hoped that we’d have bio kids, and they just can’t relate to us anymore now that we’re not going to deliver. Childless straight people, and especially childless women, may have had similar experiences.

If we queers are online, and sometimes if we’re not, we’ve had random strangers remind us, crudely, about how babies are made, and about how life would end if everyone were gay. We queers of a certain age remember: “It’s not a lifestyle, it’s a deathstyle.” To this day, our enemies may fantasize about putting us all on some island with no condoms or HIV treatments, and watching us kill one other with AIDS. They dream of a scapegoat colony, as if to keep Death distracted.

The heart of queerphobia is that we mean death to them.

The path of the mind

As a kid, I once picked up some pop science books about astronomy, scientific cosmology, and the eventual fate of the cosmos. Back then, the big unanswered question was: Big Crunch or Big Chill? That is, the universe is expanding, but will the expansion reverse course, or will it continue forever? In a Big Crunch, everything returns to a single, impossibly dense point. In a Big Chill, everything expands until no two particles ever meet each other again.

At age ten, I had opinions about those matters. I hoped for a Big Crunch. Why? Because the opposite would be a cosmic injustice. I figured that in a Big Crunch, there’d at least be a chance for life to hold together and fight back. Our descendants would figure something out, just as long as they could hold physically together. (I know, I know, it’s not even original.)

I wanted a rebirth, not through God or genes, but through science and technology. I experienced it as a matter of life and death, but in a long-term sense. To ten-year-old Jason, the future looked like growing up, and then Star Trek, and then—well, either the universe would keep on telling its story, or it would stupidly rip everything up and be dead forever.

The betterment of humankind through science and space exploration soon became my childish immortality project. I didn’t know how to arrest the death of the universe, but I did stumble onto an Asimov story that went through the same territory. It made me feel good about the future. I didn’t know what the Enlightenment was yet, but already I was an Enlightenment guy.

I’ve spent a lot of my life in a similar place; I even earned a doctorate studying the Enlightenment, the time when this kind of thinking really got underway. I married an aerospace engineer who went on to work at NASA. If I still have an immortality project, it’s about building up human knowledge and capacity, and leaving the store of it better than how we found it.

Ideas can also look like a causa sui, and the path of the mind has many advantages. For starters, its methods aren’t murderous. On the path of the mind, an idea may die—but the people who held it don’t have to. A good idea, an idea that passes our tests, can be copied and spread without leaving anyone worse off. If anyone wins, all may win. Unlike the competition among bloodlines, the competition for better ideas is positive-sum. Consider a list of the words coined by Shakespeare. If you speak English at all, then you’re among the beneficiaries of his positive-sum immortality project.

An idea can lie dormant for decades or centuries, then find new life when the times demand, like with the twentieth-century revival of Aristotle’s virtue ethics. Or like quaternions, mathematical constructs which didn’t have much immediate use when they were invented in the nineteenth century. Today they’re in computer graphics and spacecraft guidance systems. A good idea can skip across races and religious faiths. On the path of the mind, diversity isn’t a threat; a wide vocabulary of ideas is just a wide vista for your own individual freedom. Every immortality project is a lie—but here’s a nobler one than most.

From over on the path of blood, a voice calls out: “You idiot! Don’t you see that minds live in bodies, and bodies always need blood?”

That’s an easy question, because it’s empirical. We have plenty of people right now. The population will likely plateau. I might live to see a modest decline, if I reach my eighties.

None of that’s a reason to panic, though. It’s the mark of a forgotten victory: In the mid-twentieth century, we were so worried about an imminent population explosion. Now we’re supposed to be worried about a far-off and modest population decline?

We won’t run out of people. Here’s the bigger question: What will we fill their heads with? Now that’s a question worth giving your life to. Everyone is dying, and if you’re worried about that, then throw yourself into preserving knowledge. Or preserving goodness.

Live for the endangered future. As Marguerite Yourcenar wrote, with the borrowed pen of Emperor Hadrian: “To found a library was like founding a public granary; it was to amass reserves against a winter of the spirit, certain signs of which, despite myself, I could already see coming.”

Words for our times. Marguerite Yourcenar was a queer, like me, like Hadrian. But you know what? That’s not so bad either, when you’re on the path of the mind.

Elon and the Buddha

Relax, I’m not asking you to follow either one.

Elon Musk is one of our foremost religious leaders. He’s a tireless promoter and organizer of certain immortality projects. He walks both of the paths, after a fashion: His space colonization dreams are an immortality project I’ve known and loved. His natalism and racism, though, are clearly on the other path.

Musk’s glamour is that he invites you to pursue your own immortality. When you do, it’ll secure his as well: Travel to Mars, expand humanity’s footprint, because Earth might die, and you could save humanity. If you succeed, you’ll be remembered forever—as a guy who worked for him. Even if you aren’t so driven, you can still go to his social media platform and blaze your glory there; it adds a few bits to his.

Musk hasn’t founded a church, but many religious leaders never do. Still he believes in, and he ruthlessly pursues, both of the secular paths to immortality. He wants his ideas to live forever. And he’s already had at least fourteen children, the better to carry on his bloodline. He talks about raising a “legion,” and it’s not entirely clear just how far he’s already taken that. If all our bloodlines one day fall to AI, well, he’s working on that one, too.

Ah—but he’s estranged from his trans daughter: Love is because we want to keep up our species.

And what if you’re cis, but gay? “I only ask of my gay friends that they have children for the continuance of civilization,” Musk wrote on X. By this he means IVF, which grows the population—and not adoption, which doesn’t. It’s not that he disapproves of us, you see. He just asks that we have a very expensive medical procedure, and it so happens that most of us can’t afford his esteem. (Could he mean adoption instead? Probably not: “If you don’t make new humans, there’s no humanity, and all the policies in the world don’t matter,” he has also said.)

Again, every immortality project is a lie—but some lies are more nonsense than others. What Musk offers is a monstrous hybrid. It’s a rationalistic fertility cult that stinks of death and fear.

I think we’d all be better off if we could loosen our grip on these false hopes. And perhaps we can. American civic religion has always favored the path of the mind. Americanness isn’t a genetic immortality project, and in our better moments, we know that we’re something more. As Lincoln said of immigrants in 1858:

If they … trace their connection with [the American Revolution] by blood, they find they have none … but when they look through that old Declaration of Independence they find… “We hold these truths to be self-evident, that all men are created equal,” and then they feel that that moral sentiment taught in that day evidences their relation to those men, that it is the father of all moral principle in them, and that they have a right to claim it as though they were blood of the blood, and flesh of the flesh of the men who wrote that Declaration, (loud and long continued applause) and so they are. That is the electric cord in that Declaration that links the hearts of patriotic and liberty-loving men together, that will link those patriotic hearts as long as the love of freedom exists in the minds of men throughout the world.

At its best, America’s not even a people, and that fact annoys America’s enemies. America’s an idea, and ideas grow by sharing.

A people, yoked by the fear of death, will fall prey to a domineering state. That state’s leaders, anxious for their own immortal fame, are apt to treat their subjects like breeding cattle, or worse. For the survival of the nation, a people can be guarded, surveilled, imprisoned, tortured, silenced, deported, deprived of due process, and subject to ethnic cleansing.

A people is a worthy lump of clay for a tyrant. An idea, though, is not. As travelers on the path of the mind, we Americans are ecumenical and open-handed. We’ve always wanted to claim that the goodness that our polity needs can be found in any nationality, and in any world religion. Being American consists, as Lincoln knew, of ideas that are available to all. With that in mind, here are a couple of possibly useful quotes from the Buddha:

Mendicants... Out of sympathy for you, I think, “How can my disciples become heirs in the teaching, not in things of the flesh?”

It’s a recurring theme in every major religion: Cultivate what’s within, because this is the kinder way, the way of sympathy. It’s why Jesus cleansed the temple, and why Erasmus denounced indulgences. It’s why Tolstoy wrote The Kingdom of God Is Within You. It even made Yoda declare: Luminous beings are we, not this crude matter. You can be as indifferent to material things as the Buddha was, and still you can change the world.

If you must be reborn, if you must have an immortality project, walk the path of the mind. Pour your life into something that will be good for everyone. Not just for the brittle line of your future male inheritors.

The Dhammapada, which is kind of like a Buddhist creed, starts with these words:

Mind precedes all mental states. Mind is their chief; they are all mind-wrought. If with an impure mind a person speaks or acts, suffering follows him like the wheel that follows the foot of the ox.

That’s not immortality, but it is the truth.

Featured image is The Wheel of Dharmacharkra at Jogyesa Temple, by Terry Feuerborn