The Potemkin Feminism of "Sex-Based Rights"

"Sex-based rights" are a Potemkin feminism that commit us to a theory of objective sex where there is something special about your very biology that entitles you to special treatment not deserved by others.

In the music video for her 2006 party pop ballad “Todos me Miran” (Everyone Looks at Me), Mexican singer Gloria Trevi portrays a woman fleeing from her abusive husband and into the bright light of clubbing self-confidence; twinned with her story is that of a young trans woman fleeing from her abusive father. Each earns stares in the street and, in the lyrics of the song, “And everyone looks at me, looks at me, looks at me/ Because I do what few will dare.” It’s a remarkable feminist text that puts the lie to both the idea that Latin American culture is inherently patriarchal, and to the idea that cis and trans women are irreconcilably different. A theorist as much as a singer, Trevi makes clear that the root of our oppression as women—whether cis or trans—is identical, and that we must walk (and dance) hand-in-hand to the disco-ball-lit uplands of our liberation.

I take a grim satisfaction that, in this as in so much else, Trevi demonstrates vastly more subtlety and understanding than the entire Supreme Court of the United Kingdom. Their April 16th ruling, which held that trans people are not legally their sex under the auspices of the Equality Act 2010 (i.e. that, in the language of the Act, a trans woman is not legally a woman and a trans man is not legally a man) is not only a fractalizing affront to the dignity of trans people, but a miasma of legal vapourware that will choke all of Britain in its absurdities.

On both sides of the Atlantic, the tide of transphobic activism, legislation, and jurisprudence alike has been cast as a defence of women (cisgender only, of course). But to the extent that there’s a legal theory at the heart of this, you may have heard that trans people—trans women, in particular—are a threat to cis women’s “sex-based rights.”

This concept sounds reasonable and neutral, but a close examination of legal scholarship and history reveals it to be a Potemkin-façade for the smallest, meanest of bigotries. It is a fantasy, and one that certainly bears no relationship to the long tradition of feminist legal scholarship.

The centre of the legal dispute was this: if a trans woman gets a Gender Recognition Certificate, certifying her as a woman per the Gender Recognition Act of 2004, is she then legally a woman under the Equality Act of 2010? The UK Supreme Court said no; “sex” in the text of the Equality Act means “biological sex” only. Judge Lord Hodge ruled:

The unanimous decision of this court is that the terms woman and sex in the Equality Act 2010 refer to a biological woman and biological sex. But we counsel against reading this judgement as a triumph of one or more groups in our society at the expense of another, it is not.

As is often the case with John Roberts’ blue-plate specials in the US, the UK Supreme Court cast its reactionary ruling as a bid for “clarity,” with a few barely-enforceable caveats designed to provide rhetorical cover for the ruling’s defenders and little else.

Trans people, Lord Hodge claimed, retained “protection, not only against discrimination through the protected characteristic of gender reassignment, but also against direct discrimination, indirect discrimination and harassment in substance in their acquired gender.” Yet, in light of the fact that there are already rumblings about banning trans people from using the right public restrooms and changing rooms, or the fact that the Transport Police announced—in less than 24 hours—that they would now have trans women suspected of a crime frisked by male officers, we already see this for the mockery it is.

Speaking of mockeries, the chair of Britain’s Equality and Human Rights Commission, Lady Kishwer Falkner said on BBC Radio 4 that she was looking to draft statutory guidance that reflected her interpretation of the court’s ruling. As The Guardian reported:

[Falkner] said the court’s judgment meant only biological women could use single-sex changing rooms and women’s toilets, or participate in women-only sporting events and teams, or be placed in women’s wards in hospitals.

Falkner herself said, “I think the law is quite clear that if a service provider says ‘we’re offering a women’s toilet’, trans [women] should not be using that single-sex facility.”

So much for Hodge’s claim that we retained “protection.” This is, of course, not the final word on any of these issues. History marches on. But this Saturnalia of transphobic triumphalism from the British establishment cannot be leavened with their occasional disclaimers about how trans people are still nebulously protected as trans people. If banning us from using a washroom is not discrimination, what is?

In the case of British law, it is now worth wondering whether a Gender Recognition Certificate has any value whatsoever.

But the absurdities pile up even further. Much attention has rightly been given to the way that this ruling fixates luridly on transgender women—we are, after all, at the heart of much moral panic about trans people around the globe. But the ruling spared some thought for transgender men, as well, and the implications there are as dark as they are bizarre.

Consider this paragraph from the ruling:

236. On the other hand, a biological definition of sex would mean that a women’s boxing competition organiser could refuse to admit all men, including trans women regardless of their GRC status. This would be covered by the sex discrimination exception in section 195(1). But if, in addition, the providers of the boxing competition were concerned that fair competition or safety necessitates the exclusion of trans men (biological females living in the male gender, irrespective of GRC status) who have taken testosterone to give them more masculine attributes, their exclusion would amount to gender reassignment discrimination, not sex discrimination, but would be permitted by section 195(2). It is here that the gender reassignment exception would be available to ensure that the exclusion is not unlawful, whether as direct or indirect gender reassignment discrimination.

What the plain text suggests here is that even though—by dint of their own ruling!—transgender men are legally women, they cannot participate in women’s sports if they look too manly or have taken testosterone. So trans women must be excluded from large swathes of society because they are supposedly men, and trans men must be similarly excluded because they are trans.

Paragraph 221 of the ruling reiterates this idea, once again saying that discrimination is “proportionate” where a “reasonable objection” is made to their presence “because the gender reassignment process has given them a masculine appearance.” Suddenly, gendered appearance matters a great deal for defining gender, in a way that relies on wholly subjective judgment.

Far from introducing clarity, this ruling suggests that—by law—transgender men in Britain are two sexes at once: whichever one circumscribes their rights the most will be the legally salient one.

How could a ruling that relies on frequent references to “the plain meaning” of terms they never define, and upon endless subjective judgements that different ordinary people will inevitably disagree about, possibly be called “clarifying”?

But the judges don’t stop there. Less remarked upon, even in Britain’s trans-obsessed media, is the fact that this ruling has also legally defined gays and lesbians:

206. Accordingly, a person with same sex orientation as a lesbian must be a female who is sexually oriented towards (or attracted to) females, and lesbians as a group are females who share the characteristic of being sexually oriented to females. This is coherent and understandable on a biological understanding of sex. On the other hand, if a GRC under section 9(1) of the GRA 2004 were to alter the meaning of sex under the EA 2010, it would mean that a trans woman (a biological male) with a GRC (so legally female) who remains sexually oriented to other females would become a same sex attracted female, in other words, a lesbian. The concept of sexual orientation towards members of a particular sex in section 12 is rendered meaningless. It would also affect the composition of the groups who share the same sexual orientation (because a trans woman with a GRC and a sexual orientation towards women would fall to be treated as a lesbian) in a similar way as described above in relation to women and girls.

We must stand in awe of the breathtaking arrogance on display here, as dangerous as it is absurd, of a high court empowering the government of a notional democracy to remove a marginalised community’s power to define itself. Far from being “coherent,” this paragraph also creates a tar pit of nonsenses. A straight trans woman, who only dates men, would be regarded as a gay man; a cisgender lesbian with a trans woman girlfriend is legally straight; a cis man who sleeps with transgender men is legally straight (or perhaps bi? We might need the court to weigh in on that sometime—inquiring minds at the Daily Mail and the Labour frontbench might want to know, after all).

But this all flies in the face of the queer community’s right to define itself, and, in particular, for queer people ourselves to define the boundaries of our own sexualities. How would Lord Hodge deal with a cis woman whose entire experience of lesbianism has involved attraction to both cis and trans women, but never once to a self-identified man? And why must such a question be put to aristocratic judges in the first place?

The absurdities of the ruling are self-evident after a moment’s thought. To follow the jurists’ logic here is to enter a Kafkaesque gender order that is rapidly eating itself alive from within. Non-binary people are in more legal limbo than ever, once again putting the lie to the idea of “clarity,” loudly touted by the British media and various organisations clamouring to implement trans-exclusionary policies. I haven’t even mentioned how this will create countless lawsuits from cis people fighting amongst themselves—a tomboy girl kicked off her football team, a gender-non-conforming cis woman frisked by a male police officer, or a butch cis woman harassed out of a loo at her local pub. They’ll all have the British establishment’s long-running obsession with trans people to thank.

But it’s all in the service of defending women’s “sex-based rights,” after all. And, of course, “clarity.” The British media, in particular, has trumpeted that idea of “clarity” loudly, and in bold text, as have any number of politicians. But what this ruling achieves is obfuscation on a grand scale, solving an alleged rhetorical confusion that never existed in the first place.

On the matter of sex and gender, the law lords notionally provided “clarity” by saying the two concepts are completely different. But we’re already learning that the people who helped draft the Equality Act 2010 had a rather different view of the matter. In, of all things, a LinkedIn post, a civil servant who worked on the bill had to publicly say,

The policy and legal instructions underlying its drafting were based on the clear premise that, for a person with a Gender Recognition Certificate (GRC), their “sex” for the purposes of the EA is that recorded on their GRC. This position, as it relates to sex discrimination law, was set out clearly in the explanatory notes to the Gender Recognition Act 2004 (GRA) - the Equality Act did not seek or purport to change that approach.

This directly contradicts the Supreme Court’s repeated assertion that there was some perverse lack of clarity, or some abundance of contradictions in the Equality Act. This comes from Melanie Field who, at the time, was the deputy director at the Government Equalities Office—a unit of the powerful Cabinet Office. She was, in her own words, responsible for “having led the development and passage of the Equality Act 2010.”

Unlike in the esoteric legal debates about the intentions of America’s Founding Fathers, who are centuries-dead, we can rather easily ask the people who worked on the Equality Act what they were thinking. It seems no one on the Court thought to do so, just as they refused to take evidence from trans people.

Defining sex as narrowly as this court has done is dangerous because it traps people (most especially women) in stereotypes fixed in the amber of the present day. To that end, Fields shares something quite concerning that needs to be quoted in full. In short, she identifies a political change to the wording of the legislation—one she was forced to make—which the Supreme Court seemed to rely upon in coming to their judgment:

The inclusion of the word “woman” in the pregnancy and maternity provisions was contentious – we were well aware of the possibility of a trans man with a GRC becoming pregnant. The drafting was eventually determined for political reasons, and reluctantly implemented by officials on the basis that the purposive approach to statutory interpretation, together with the explicit provision in the GRA that a GRC does not affect parenthood, would give the right result should a case ever be brought by a trans man in this situation. However, it is true that this undermines the coherence of the drafting and I fear that this anomaly played a significant role in the approach taken by the Court. This highlights the danger of allowing politics to influence legislative drafting – something we should continue to guard against as the implications of this judgment are worked through and any amendments to ensure the law works as it should are contemplated.

When one relies on a politically biologized definition of women, you open the door to legal perversities. And that does appear to be what happened here. Instead of neutrally describing pregnancy—as a sex equality approach would demand—a political decision was made to, in the text of a law that binds peoples’ lives, describe pregnancy as a defining property of womanhood; a social, lived gender as much as a sex.

When it comes to pregnancy discrimination and the provision of care, the overwhelming supermajority of people protected will be cis women. But from the legal perspective of preventing sexually-based discrimination, trans men and nonbinary people must also be within the ambit of that protection. There is no way to understand antagonism towards a pregnant enby as anything other than sex-based discrimination, after all.

So what about sex-based rights?

Over the last several years, “sex-based rights” is a term that has insidiously seeped into mainstream discourse with all its inoffensive pretences to neutrality. On the surface it seems to make intuitive sense: this is how one describes the rights that protect you from sexual discrimination.

Except not. As we’ve already seen, there is an enormous difference between the human right to “not be discriminated against on the basis of sex,” and the idea of a right based on one’s sex; the latter is, in many ways, a literalisation of the conservative bogeyman of “special rights,” which they conjure in order to deny people equal protection under the law. Yet now it’s described positively by conservatives. Why?

To protect one from sex-based discrimination is to protect one’s human dignity from being assaulted by the prejudices of others—by their perceptions, beliefs, delusions, opinions about one’s sexed body. But to invest someone with sex-based rights is to commit both them and you to a whole theory of sex that must be objectively defined, where there is something special about your very biology that entitles you to special treatment not deserved by others. This is the film-negative of a civil right.

That suits right-wing ends just fine. They have a clear ideological project that both denies human equality and creates sex castes. The idea of a sex-based right works within a framework of easily defined men and women, where never the twain shall meet. Democratic jurisprudence, meanwhile, has to take a different approach: that identity is not the basis of a special right, but merely something to be recognised by the law in its quest to ensure all receive equal protection.

To be legally cognisant of sex, race, disability, sexual orientation, et cetera, is not to argue that there are, say, ‘race-based rights,’ but that these are categories along which one may experience discrimination that violates both one’s dignity and citizenship. One is legally cognisant of sex-based discrimination so that one can protect the victim’s humanity from an attempt to cleave them away into a biologised category that implicitly deserves fewer rights. That is, after all, the corollary to any idea of identity-based rights.

To look at the legal literature is to find few mentions of “sex-based rights” as an idea until fairly recently, despite decades of scholarship, argument, and caselaw relating to women’s rights. And in feminist legal literature, the lines are even more stark. Catharine MacKinnon, an actual radical feminist whose impressive legal scholarship and legal advocacy helped provide the basis for caselaw about sexual harassment in the US, makes no bones about any of this when she addressed recent controversies about trans people:

An emerging direction in sex equality law—one I have taught and sought for decades for both sexual orientation and transgender rights—is that discrimination against trans people is discrimination on the basis of sex, that is gender, the social meaning of sex. This recognition does not, contrary to allegations of anti-trans self-identified feminists, endanger women or feminism, including what some in this group call “women’s sex-based rights.” To begin with, women—in the United States anyway—do not have “sex-based rights” in the affirmative sense some in this group seem to think. We do have (precious few) negative rights to be free from discrimination on the basis of sex—which has almost always meant gender, actually—and so do men.

The entire purpose of the “sex-based rights” distinction is to create a feminist-ish phrase that justifies the exclusion of transgender people—trans women, in particular—and casts that as a “protection” of women. MacKinnon’s argument here is that sex and gender, so far as any legal architecture defending what she calls our “sex equality rights” is concerned, are the same. Further, equality as a legal framework generally pushes against sex-segregation as a concept. It is, she says, an anachronism rather than a product of the late 20th century’s big push for women’s equality.

Even sensitive spaces like prisons, she argues, are not expressions of those hard-won rights. “Incarcerated women,” she says, “have no ‘sex-based rights’ to be incarcerated in all-women’s prisons. They are separated by sex for state and police power reasons of security, management, and administration.” She goes on to note that women’s prisons are places where women are victimised by other women, both guards and other inmates. “The primary threat to women prisoners remains prison guards, who mainly are men; sexual abuse in prisons is systematic and institutionally normalized. The dangers incarceration poses for women do not begin with trans women who seek to be housed in women’s facilities, often to prevent being systematically raped in men’s prisons or to be in a less brutal overall environment.”

Note that this never comes up, on either side of the Atlantic, when the supposed defenders of women’s “sex-based rights” talk about incarcerated women. They wish to protect the incarcerated from the sight of a transgender woman—and nothing more.

The heart of MacKinnon’s argument, however, draws from what is arguably her greatest legal accomplishment: the caselaw surrounding sexual harassment in the United States. She argues cogently, both from experience and as a matter of legal theory, that any “sex-based” approach to it would’ve rendered protection from sexual harassment impossible. She understands the obvious: to invoke sex and not view it as gender/gendered is to suggest something is natural and inalterable, and therefore beyond the reach of the law. This has particular and perverse implications for women’s rights.

When courts find an overwhelmingly sex-differential disadvantage, or even a perfect sex-based disadvantage, they think they have found sex, not sex inequality. If not for the gender argument, separating sexuality as social from sex as biological—which can ground invidious treatment, as opposed to permitting sex-differential violation as natural and inevitable—sexual harassment would have been considered a sex-based difference, hence not a basis for discrimination, I promise you. In fact, until a specific gender analysis was argued (by me, in this case), it was. How other women are threatened by including trans women in this protection, as they have been since the 1990s, escapes me.

It was only by unpicking this knot that lawyers were able to argue that sexual harassment was subject to legal scrutiny as a form of sex-based discrimination. Again and again, the term “sex-based” has been most properly used to define what we seek protection from. MacKinnon rehearses arguments here that many will be familiar with—that transphobes, including trans-exclusionary feminists, are being biologically essentialist, for instance, and at odds with crucial feminist insights. It is critical to MacKinnon’s thought, however. Indeed, it’s foundational.

In her 1989 book, Toward a Feminist Theory of the State, MacKinnon excoriates Friedrich Engels’ early but influential attempt to explain the subjection of women as a function of biology: “He not only does, but must, assume male dominance at the very points at which it is to be explained.” She later makes the same critique of many Second Wave feminists who, she argues forcefully, merely describe what they purport to explain. Quoting from Simone de Beauvoir’s The Second Sex, MacKinnon argues “here it is not the meaning society has given women’s bodily functions, but the functions themselves, existentially that oppress women,” arguing that “woman’s oppression is present at Beauvoir’s account of its birth.”

This is all, in many ways, the fulcrum upon which MacKinnon’s thought rests.

“It is one thing to identify woman’s biology as a part of the terrain on which a struggle for dominance is acted out; it is another to identify woman’s biology as the source of that subordination,” she writes. Such thought informed her later stance on trans rights. To return to her 2023 paper,

When feminists define women from the dictionary as ‘adult human female,’ in biologically essentialist terms—adult is biological age, human is biological species, female is biological sex—sliding sloppily from “female” (sex) through “feminine” (gender) to “woman,” as if no move has been made, they not only give the wrong answer, they are answering the wrong question. And they are ensuring that they can at most address excesses of male power, never that power itself.

The entire business of “sex-based rights,” a confected term that only serves to redouble sex-based discrimination, is thus revealed as unfit for anything other than the narrow purpose of humiliating transgender women. For women as a whole, it is a term that narrows the horizon of women’s rights to the width of a bathroom door.

Perhaps the single greatest atrocity in the UK Supreme Court’s ruling is that it has now brought this idea—expansive in its absurdity and narrow in its dignity—to the heart of British law in ways that will have very real consequences while doing nothing to advance women’s rights in any meaningful sense. Indeed, feminism in Britain is inching toward its deathbed, not in spite of all this, but precisely because of it. After all, nearly all public discourse about women’s rights have now been funneled into that bathroom stall, where we must all loudly pretend that a sex-segregated changing room is what generations of feminists fought and died for, rather than a holdover of decidedly Victorian gender norms.

The brave new world that people like Falkner have proposed is that third-sexed spaces be created for trans people. A new fungal spore of those old gender norms. It’s risible, in no small measure because—as she herself admits—even in her maximalist interpretation of the ruling, no institution is required to offer sex-segregated facilities. Therefore, it stands to reason that they will not be required to provide a third space for trans people. We’re reduced to subsisting on her logistical fairy-tales as a substitute for human dignity because some people couldn’t let go of their need to pave over sex equality with the idea of “sex-based rights.”I do not wish to leave my British siblings without any sense of hope, but it is difficult. The court has obliterated a lot of the architecture of transgender rights in its jurisdiction. But new caselaw can (and must) be built on the ashes, both on a sex equality framework, and using the insights from American law that have helped guard the rights of women, cis and trans, here.

One of the most useful bits of jurisprudence in the US for trans rights rests on the claim that sex discrimination can occur when one polices gender presentation.

This wasn’t always the case. As legal scholar Kylar Broadus writes in his history of the caselaw, it was not uncommon for courts to conclude that Title VII of the Civil Rights Act, which outlaws sexual discrimination, excludes transgender people. In the 1975 case Voyles v. Ralph K. Davies Medical Center, the court ruled against the trans plaintiff arguing that “sex” must be given “its plain meaning,” poorly defined in the manner of the UK Supreme Court’s ruling half a century later. But US jurisprudence took a different direction.

In Price Waterhouse v. Hopkins, a cisgender woman successfully sued for sexual discrimination because her bosses had denied her a partnership at the law firm on the basis of her not wearing a skirt and heels. That case has been used as the basis for cases explicitly about trans rights. What makes this useful is that it sidesteps the philosophical question about who gets to be a woman. It doesn’t matter. If you think I’m a man, and discriminate against me because I often wear a skirt, then you’ve still engaged in sexual discrimination.

As Broadus wrote in “The Evolution of Employment Discrimination Protections for Transgender People,” in the wake of this ruling, “courts increasingly have been hard-pressed to explain why the reasoning in [Price Waterhouse] would not apply equally to a transgender person.” In every event, “the employer has discriminated on the basis of sex by ‘assuming or insisting that employees match the stereotypes associated with their group,’” he argues, quoting from Price Waterhouse.

Broadus wrote this in 2006. Fourteen years later, the legal logic he identified resolved in the fullest bloom of fruition in the landmark US Supreme Court case Bostock v. Clayton County, which held that Title VII also protects people from discrimination on the basis of gender identity or sexual orientation, building on two decades of cases from lower courts that had come around to the same view.

Writing for a surprising 6-3 majority in Bostock, Justice Neil Gorsuch argued, “An employer who fires an individual for being homosexual or transgender fires that person for traits or actions it would not have questioned in members of a different sex. Sex plays a necessary and undisguisable role in the decision, exactly what Title VII forbids.”

This seems the proper domain of law. It is for us as free citizens to discuss and debate the bounds of our identities, our genders, our sexualities. It is not for a judge to decide. Sex is a unitary protective category in this framework, on which basis one cannot be discriminated against. It does not matter whether one believes there are two sexes or two thousand, only that you be protected from discrimination based on someone else’s perception of it, in a word, your gender. Gender and sex are two sides of the same coin here because they must be in order for legal protections to work. As MacKinnon and many other feminist theorists have rightly observed, it is gender presentation that often determines the shape of sexual discrimination.

To be blunt, out in the real world, discriminatory practice does not begin with a karyotype test. When a young man leaned out his car window to shout at me “hey, nice legs, when do they open!?” the moral injury of that harassment was not determined by my gametes but by my dignity as a human being. I know that this form of abuse accrues to feminine people like myself, but it also should not be the basis on which we define some hard boundary of womanhood. The injury was to my humanity, on the basis of my sex—however that man perceived it.

And as to how we define ourselves affirmatively? We are, and we must always be, known by more than the scars inflicted upon us by hierarchy and oppression. That is a civilisational gift, as is the idea that we are more than the circumstances of our birth, and that we can be more than our bodies.

Democracy writ large rests on these ideas, on the ability for free people to determine their own destinies. British democracy has lain bleeding for years, riven by myriad, suicidal wounds. But history is never over. This grotesque, bleak nadir, is yet only the middle of the story. Now is the time to fight back. In that, at least, is a dignity no court can take away.

Support Opposition Media

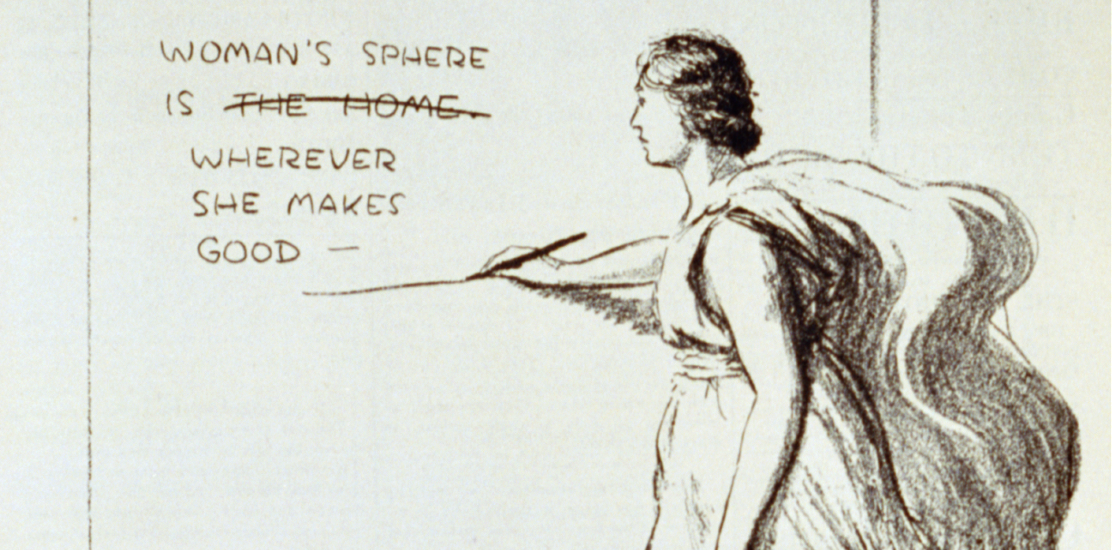

Featured image is "Revised / Chamberlain," Kenneth Russel Chamberlain 1917. Cropped.