The Essentials in the Struggle

- What follows is the final chapter of Dr. Du Bois’s 1896 book The Suppression of the African Slave-Trade to the United States of America, 1638–1870.

Much historical research since Du Bois’s time has added to and in some respects may have altered our understandings. And Du Bois’s 1950s expression of dismay at not having been much aware of Freud and Marx when the 1896 book was written should be read, but it would be unfortunate to consider it dispositive. His analysis and conclusions presented here may resonate more with readers today than with those a few decades ago.

How the question arose

We have followed a chapter of history which is of peculiar interest to the sociologist. Here was a rich new land, the wealth of which was to be had in return for ordinary manual labor. Had the country been conceived of as existing primarily for the benefit of its actual inhabitants, it might have waited for natural increase or immigration to supply the needed hands; but both Europe and the earlier colonists themselves regarded this land as existing chiefly for the benefit of Europe, and as designed to be exploited, as rapidly and ruthlessly as possible, of the boundless wealth of its resources. This was the primary excuse for the rise of the African slave-trade to America.

Every experiment of such a kind, however, where the moral standard of a people is lowered for the sake of a material advantage, is dangerous in just such proportion as that advantage is great. In this case it was great. For at least a century, in the West Indies and the southern United States, agriculture flourished, trade increased, and English manufactures were nourished, in just such proportion as Americans stole Negroes and worked them to death. This advantage, to be sure, became much smaller in later times, and at one critical period was, at least in the Southern States, almost nil; but energetic efforts were wanting, and, before the nation was aware, slavery had seized a new and well-nigh immovable footing in the Cotton Kingdom.

The colonists averred with perfect truth that they did not commence this fatal traffic, but that it was imposed upon them from without. Nevertheless, all too soon did they lay aside scruples against it and hasten to share its material benefits. Even those who braved the rough Atlantic for the highest moral motives fell early victims to the allurements of this system. Thus, throughout colonial history, in spite of many honest attempts to stop the further pursuit of the slave-trade, we notice back of nearly all such attempts a certain moral apathy, an indisposition to attack the evil with the sharp weapons which its nature demanded. Consequently, there developed steadily, irresistibly, a vast social problem, which required two centuries and a half for a nation of trained European stock and boasted moral fibre to solve.

The moral movement

For the solution of this problem there were, roughly speaking, three classes of efforts made during this time,—moral, political, and economic: that is to say, efforts which sought directly to raise the moral standard of the nation; efforts which sought to stop the trade by legal enactment; efforts which sought to neutralize the economic advantages of the slave-trade. There is always a certain glamour about the idea of a nation rising up to crush an evil simply because it is wrong. Unfortunately, this can seldom be realized in real life; for the very existence of the evil usually argues a moral weakness in the very place where extraordinary moral strength is called for. This was the case in the early history of the colonies; and experience proved that an appeal to moral rectitude was unheard in Carolina when rice had become a great crop, and in Massachusetts when the rum-slave-traffic was paying a profit of 100%. That the various abolition societies and anti-slavery movements did heroic work in rousing the national conscience is certainly true; unfortunately, however, these movements were weakest at the most critical times. When, in 1774 and 1804, the material advantages of the slave-trade and the institution of slavery were least, it seemed possible that moral suasion might accomplish the abolition of both. A fatal spirit of temporizing, however, seized the nation at these points; and although the slave-trade was, largely for political reasons, forbidden, slavery was left untouched. Beyond this point, as years rolled by, it was found well-nigh impossible to rouse the moral sense of the nation. Even in the matter of enforcing its own laws and co-operating with the civilized world, a lethargy seized the country, and it did not awake until slavery was about to destroy it. Even then, after a long and earnest crusade, the national sense of right did not rise to the entire abolition of slavery. It was only a peculiar and almost fortuitous commingling of moral, political, and economic motives that eventually crushed African slavery and its handmaid, the slave-trade in America.

The political movement

The political efforts to limit the slave-trade were the outcome partly of moral reprobation of the trade, partly of motives of expediency. This legislation was never such as wise and powerful rulers may make for a nation, with the ulterior purpose of calling in the respect which the nation has for law to aid in raising its standard of right. The colonial and national laws on the slave-trade merely registered, from time to time, the average public opinion concerning this traffic, and are therefore to be regarded as negative signs rather than as positive efforts. These signs were, from one point of view, evidences of moral awakening; they indicated slow, steady development of the idea that to steal even Negroes was wrong. From another point of view, these laws showed the fear of servile insurrection and the desire to ward off danger from the State; again, they often indicated a desire to appear well before the civilized world, and to rid the “land of the free” of the paradox of slavery. Representing such motives, the laws varied all the way from mere regulating acts to absolute prohibitions. On the whole, these acts were poorly conceived, loosely drawn, and wretchedly enforced. The systematic violation of the provisions of many of them led to a widespread belief that enforcement was, in the nature of the case, impossible; and thus, instead of marking ground already won, they were too often sources of distinct moral deterioration. Certainly the carnival of lawlessness that succeeded the Act of 1807, and that which preceded final suppression in 1861, were glaring examples of the failure of the efforts to suppress the slave-trade by mere law.

The economic movement

Economic measures against the trade were those which from the beginning had the best chance of success, but which were least tried. They included tariff measures; efforts to encourage the immigration of free laborers and the emigration of the slaves; measures for changing the character of Southern industry; and, finally, plans to restore the economic balance which slavery destroyed, by raising the condition of the slave to that of complete freedom and responsibility. Like the political efforts, these rested in part on a moral basis; and, as legal enactments, they were also themselves often political measures. They differed, however, from purely moral and political efforts, in having as a main motive the economic gain which a substitution of free for slave labor promised.

The simplest form of such efforts was the revenue duty on slaves that existed in all the colonies. This developed into the prohibitive tariff, and into measures encouraging immigration or industrial improvements. The colonization movement was another form of these efforts; it was inadequately conceived, and not altogether sincere, but it had a sound, although in this case impracticable, economic basis. The one great measure which finally stopped the slave-trade forever was, naturally, the abolition of slavery, i.e., the giving to the Negro the right to sell his labor at a price consistent with his own welfare. The abolition of slavery itself, while due in part to direct moral appeal and political sagacity, was largely the result of the economic collapse of the large-farming slave system.

The lesson for Americans

It may be doubted if ever before such political mistakes as the slavery compromises of the Constitutional Convention had such serious results, and yet, by a succession of unexpected accidents, still left a nation in position to work out its destiny. No American can study the connection of slavery with United States history, and not devoutly pray that his country may never have a similar social problem to solve, until it shows more capacity for such work than it has shown in the past. It is neither profitable nor in accordance with scientific truth to consider that whatever the constitutional fathers did was right, or that slavery was a plague sent from God and fated to be eliminated in due time. We must face the fact that this problem arose principally from the cupidity and carelessness of our ancestors. It was the plain duty of the colonies to crush the trade and the system in its infancy: they preferred to enrich themselves on its profits. It was the plain duty of a Revolution based upon “Liberty” to take steps toward the abolition of slavery: it preferred promises to straightforward action. It was the plain duty of the Constitutional Convention, in founding a new nation, to compromise with a threatening social evil only in case its settlement would thereby be postponed to a more favorable time: this was not the case in the slavery and the slave-trade compromises; there never was a time in the history of America when the system had a slighter economic, political, and moral justification than in 1787; and yet with this real, existent, growing evil before their eyes, a bargain largely of dollars and cents was allowed to open the highway that led straight to the Civil War. Moreover, it was due to no wisdom and foresight on the part of the fathers that fortuitous circumstances made the result of that war what it was, nor was it due to exceptional philanthropy on the part of their descendants that that result included the abolition of slavery.

With the faith of the nation broken at the very outset, the system of slavery untouched, and twenty years’ respite given to the slave-trade to feed and foster it, there began, with 1787, that system of bargaining, truckling, and compromising with a moral, political, and economic monstrosity, which makes the history of our dealing with slavery in the first half of the nineteenth century so discreditable to a great people. Each generation sought to shift its load upon the next, and the burden rolled on, until a generation came which was both too weak and too strong to bear it longer. One cannot, to be sure, demand of whole nations exceptional moral foresight and heroism; but a certain hard common-sense in facing the complicated phenomena of political life must be expected in every progressive people. In some respects we as a nation seem to lack this; we have the somewhat inchoate idea that we are not destined to be harassed with great social questions, and that even if we are, and fail to answer them, the fault is with the question and not with us. Consequently we often congratulate ourselves more on getting rid of a problem than on solving it. Such an attitude is dangerous; we have and shall have, as other peoples have had, critical, momentous, and pressing questions to answer. The riddle of the Sphinx may be postponed, it may be evasively answered now; sometime it must be fully answered.

It behooves the United States, therefore, in the interest both of scientific truth and of future social reform, carefully to study such chapters of her history as that of the suppression of the slave-trade. The most obvious question which this study suggests is: How far in a State can a recognized moral wrong safely be compromised? And although this chapter of history can give us no definite answer suited to the ever-varying aspects of political life, yet it would seem to warn any nation from allowing, through carelessness and moral cowardice, any social evil to grow. No persons would have seen the Civil War with more surprise and horror than the Revolutionists of 1776; yet from the small and apparently dying institution of their day arose the walled and castled Slave-Power. From this we may conclude that it behooves nations as well as men to do things at the very moment when they ought to be done.

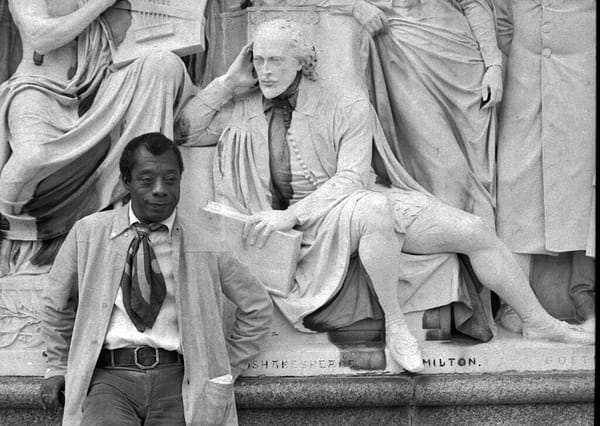

Featured image is Du Bois photographed at Harvard, 1890.