The Current Administration Is Anything But Realist

On the basic incoherence of foreign policy under Trump and Vance.

The stance taken towards Ukraine has marked a wholesale shift in US foreign policy, the ramifications of which are difficult to predict. A confrontation in the Oval Office, where Donald Trump and JD Vance attempted to pressure Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelenskyy into signing away hundreds of billions of dollars in mineral wealth, has gotten most of the attention. Indeed, the incident was so unusual, and so overtly avaricious, that the attention it has gotten is unsurprising. However, the shift in relations began somewhat earlier, with the US voting against a UN resolution urging Russia to withdraw from Ukraine—a position shared by only 17 other countries (including Russia, North Korea, and Israel). The rift has now entered crisis proportions, with Donald Trump cutting off aid to Ukraine already committed by Congress and ceasing to share intelligence.

Vance's role in the Oval Office meeting, asking Zelenskyy if he had thanked America for its aid ‘even once’ (Zelenskyy has done so dozens of times) was notable for its belligerence, unusual for a Vice President, but his nomination for that office seems to have been designed from the beginning to ensure this outcome. He has long been a favorite of Silicon Valley oligarchs like Elon Musk, Peter Thiel, and David Sacks, leaders of a reactionary cohort that seeks deregulation of tech companies domestically and in many cases favors a rapprochement with Russia in foreign policy. Sacks and Musk in particular have long pushed the idea that American involvement in Ukraine risks a wider war, and that Ukrainian sacrifice of territory should be encouraged (read: coerced) by US foreign policy. This appears to have become the dominant position in the White House, with Vance scolding Europeans about the need to protect ‘Free Speech’ as a higher priority than defending against Russian aggression, and Trump posting on social media that Ukrainian president Volodymyr Zelenskyy is a ‘dictator’ responsible for starting the war. The recent dust up in the Oval Office is just a continuation of this trend.

The shift nonetheless caught many in the foreign policy establishment off guard, as even most Republicans support Ukraine over Russia. Others, however, have been working to build an intellectual case, flimsy as it may seem, for this kind of diplomatic revolution. In trying to bolster the credibility of Trump and especially Vance’s view of foreign policy, The American Conservative hailed Vance’s appointment as a “Foreign Policy Realist”. The word ‘realist’ is of course carefully chosen—‘Realists’ enjoy the title that makes the rest of us seem somehow separated from reality. It’s thus an attractive title—but not one that fits Vance (or, it seems, anyone in the White House) even on its own terms. This is all the more apparent now that the world has seen Vance’s ‘diplomacy’ in action.

The idea that the aggressor states of the world are of no real concern to us on the American continent is certainly not a new one. When Franklin Roosevelt delivered his “Quarantine Speech,” he largely laid out the opposing, liberal view—that:

…if we are to have a world in which we can breathe freely and live in amity without fear—the peace-loving nations must make a concerted effort to uphold laws and principles on which alone peace can rest secure. The peace-loving nations must make a concerted effort in opposition to those violations of treaties and those ignorings of humane instincts which today are creating a state of international anarchy and instability from which there is no escape through mere isolation or neutrality.

This speech earned Roosevelt animosity from isolationists, including major newspapers and the America First Committee. These of course failed to keep the US out of the war, and isolationism as a political doctrine lost most of its influence. However, this doesn’t mean that Roosevelt’s liberalism won out—instead, realism as a doctrine of international relations arose to challenge many liberal assumptions. Hans Morgenthau’s book Politics Among Nations: The Struggle for Power and Peace is seen as the seminal work for this perspective on international relations, though Morgenthau drew from older ideas from thinkers like Niccolo Machiavelli and Thomas Hobbes. What all had in common was that they sought to be clearheaded and unidealistic about how international politics works and respond accordingly. The result was an emphasis on power and security, defined in strictly amoral terms, as the overarching goals of both war and diplomacy.

The most prominent proponent of foreign policy realism today in the US is almost certainly John Mearsheimer, whose 2001 book The Tragedy of Great Power Politics is a must-read text for modern international relations theory. In addition to the basic principles of realism advanced immediately following World War II—that states are the primary actors in an anarchic global system, that their primary concern is security, and that the unpredictability of state behavior means only power can maintain security—Mearsheimer asserts the importance of a “counter hegemony” or “offshore balancing” model. There are strong critiques to be made of Mearsheimer’s specific stances—particularly on Ukraine, he has shifted from arguing for a Ukrainian nuclear deterrent because Russian revanchism is near inevitable, to arguing that actually the Russian invasion of Ukraine was caused by NATO expansion. But we can safely take Mearsheimer as a prime example of realism in American international relations discourse today and see if the current Republican ticket lives up to it.

Counter-hegemony in theory

Offshore balancing and counter hegemony are based on the idea that oceans are powerful barriers to the deployment of military power, and thus it is effectively impossible, as well as unnecessary, to be a global hegemon (a state of unrivaled power in any part of the world). Instead, states need strive only for regional hegemony, dominance of their immediate landmass. A state in such a position then need only fear other regional hegemons—thus, it should also seek to prevent the creation of other regional hegemons. Thus, World War I was fought by England to prevent the rise of a German hegemon in Europe, and World War II in the Pacific was fought by the US to prevent the rise of a Japanese hegemony in East Asia.

The United States, blessed as it is with broad oceans on either side and less militarily potent neighbors, is easily a regional hegemon. The only fear it faces is that another regional hegemon will arise that can both dominate its own sphere and make alliances to encroach on ours. This means countering the potential power of any regional hegemon that might arise in the Middle East, East Asia, or Europe and Russia (other regions being, at present, less economically powerful).

Russia and China are the only reasonable hegemons to consider in this way of thinking. Within Europe, Russia could gain the capacity, and seems to have the aspiration, to become the dominant power. While the European Union is dramatically wealthier than Russia, it lacks a nuclear arsenal on a Russian scale, and even in conventional weaponry was likely lagging prior to the war in Ukraine. This, along with Russia’s immense natural resources, makes it a potential hegemon in Europe despite its relatively small population and unproductive workforce.

China by contrast is a truly massive state, the first in over a hundred years to be a true economic match for the United States. Given the concentration of the global population in East and Southeast Asia and the rapid rate of capital construction there, China’s ability to dominate the region would, in Mearsheimer’s view, constitute at least a potential problem for US security. This is exacerbated by the entanglement of the US economy with Asian states like South Korea, Japan, and Taiwan—should any of these come under Chinese hegemonic influence, the US could face economic harm, and China could establish itself geopolitically as a regional hegemon in charge of a crucial world region.

The Middle East does not have the same density of capital or population as East Asia, but the immense oil reserves there make it geopolitically important. Here, however, the US has ensured that there is no potential hegemon. Iraq once threatened to take this position, but multiple wars with the US have decimated its capacity; indeed, the Iraqi state cannot really claim hegemony within its borders. Egypt is populous but poor, and its military has a poor record of success in anything except controlling the country. Israel is the opposite—wealthy and with a highly efficient military, but without a population base to support regional hegemony (not to mention huge ideological barriers to cooperation with its neighbors). And Iran, though much feared, has shown itself mostly incapable either of directly striking Israel or offering any substantive protection to its proxies in Lebanon or Yemen. The overthrow of the Assad regime in Syria has further weakened Iran’s ability to threaten hegemonic power. Thus, we can say the Middle East is fundamentally a well-balanced situation, geopolitically speaking. This does not mean stable, and indeed a rough balance of power often spells tragedy for the people of a region caught between rival powers—but these things do not concern realists.

Having surveyed the potential hegemons in each region, a closer examination of policy statements and proposals will reveal in none of these three regions does the Trump-Vance(-Musk) administration represent a counter-hegemony perspective.

Allowing a hegemon in europe

In Europe, Vance has indeed followed Mearsheimer’s advice in downplaying the importance of Ukraine, but here Mearsheimer’s analysis is fundamentally flawed. As Mearsheimer himself knew in writing Tragedy, Russia was always a potential hegemon if its economy recovered from the post-Soviet collapse. It has now more than done so, on the back of surging fossil fuel demand. Russia’s economy may not be nominally as powerful as those of the countries west of it, but it is self-sufficient in most important resources, unlike Europe. Moreover, Russia had, before its invasion of Ukraine, a stockpile of tanks, artillery, and munitions for both that dwarfed anything on the European continent. While these stocks have been depleted, Russia’s massive military spending, and lower costs of procurement, mean that the Russian armed forces are likely to be able to rebuild those losses to a degree that Europe can only match with significant difficulty. Russia also has the industrial capacity to supply its army with shells far in excess of what Europe can match. And Europe’s great industrial power, Germany, is decidedly not a nuclear power; given that it lacks even nuclear power plants, it is unlikely to become one in the future.

All of this indicates that Mearsheimer’s early 2000s prediction that either Germany or Russia would be a future hegemon in Europe was close to correct, but that there is in fact no real competition between the two. In a decade, when Putin is likely dead and fossil fuels are hopefully less crucial to the European (and perhaps global) economy, this may shift. But until then, Russian control over Eastern Ukraine, especially industrial centers like Kharkiv and Dnipro, would be a disaster for the European balance of power, and it’s entirely contrary to a counter-hegemonic position to claim ‘not to care’ about Ukraine.

And while there may be a broad ocean between Europe and the US, and while it’s unlikely that Russia could directly project force in a way that challenged the US in North America, the results of allowing Russian hegemonic control over Europe could still be dire. For one thing, a Russian Federation stretching from the Pacific to the Dnipro could likely force apart NATO, undermining the independence of states like Estonia or Romania until the US, and the rest of NATO’s members, lost any diplomatic credibility. Another major danger is that Russia gains control of, or at least easier access to, key European technological centers. To take one example: the Dutch firm ASML, responsible for the most advanced photolithography machines needed in the production of computer chips, has thus far cooperated with US restrictions on exporting its most advanced technology to China, and of course is forbidden by the EU from sending those strategically critical machines to Russia. However, in the event that NATO is broken and Russia is able to exert force across the continent, such restrictions are unlikely to last, and US technological advantages could quickly be lost.

A fully ideological commitment to Israel

By contrast with his “America’s shortest possible term interests first” stance on Ukraine, Vance absolutely abandons Realism in his consideration of Israel, saying in 2024 that “A majority of citizens of this country think that their savior, and I count myself a Christian, was born, died, and resurrected in that narrow little strip of territory off the Mediterranean. The idea that there is ever going to be an American foreign policy that doesn’t care a lot about that slice of the world is preposterous.” Obviously, this clashes quite directly with a clear-headed view of global politics that seeks the security of one's own country ahead of any ideological commitment.

Neither Vance nor Trump has proposed any limits to American support for Israel; indeed, Israeli aid and the linked aid to Egypt were the only categories of foreign aid not halted shortly after the inauguration. Both Trump and Vance seem dedicated to seeing the US support Israel’s military conflicts throughout the region and have even threatened to alienate close Middle Eastern allies doing so. There is no real counter-hegemonic argument for this stance. Israel is not a necessary counter to Iranian influence—indeed, it is uniquely ill suited to that purpose. The biggest obstacle to Iranian hegemony in the Middle East is mistrust between the Sunni Arab majority in most countries there and Iran’s Persian Shia leadership. The success of the Sunni militant group HTS is overthrowing the Iranian-allied Assad regime in Syria demonstrates this amply. But antipathy towards Israel cuts straight across these divisions and makes it more difficult for the US to prop up any actual opposition to Iranian expansionism, and constantly running diplomatic cover for Israel isolates the US from potential allies in the UN and elsewhere. All this is done without even a feigned realistic motivation.

A shallow ‘pivot’ to Asia

Many Realists have argued the US needs to pivot to the Asia-Pacific region, even if it means abandoning some commitments in Europe. This is one way Vance could justify his desire to abandon Ukraine. But he doesn’t seem to have support from the Republican party in managing this. The official Republican Party Platform in 2024 removed any mention of Taiwan—for the first time in decades. Moreover, Trump has taken to discussing Taiwan in largely the same tones he discusses NATO, claiming that Taiwan should ‘pay us’ for its defense, in much the way he pushed a rather nonsensical claim about NATO countries failing to pay their ‘bills’. Vance may argue that US foreign policy should be focused on countering China, but his party seems to have missed the memo.

Moreover, the nomination of Elbridge Colby for Undersecretary of Defense for Policy undercuts the goal of pivoting effectively to defending Taiwan, even as it is sold as the opposite. Colby has been criticized for being too much of a ‘dove’ on Iran, but the real problem is his cavalier attitude towards Taiwan. Colby has proposed that in the event that China seems poised to annex Taiwan, the US should take it upon itself to destroy crucial Taiwanese industry, like the microchip foundry TSMC. Openly declaring this policy, however, is entirely at odds with trying in practice to defeat Chinese hegemony in Asia. A determined Taiwanese resistance to PRC occupation could potentially succeed in repelling an invasion and, barring that, severely degrade the People’s Liberation Army’s ability to threaten any other neighbors. However, knowing that its closest ‘ally’ is waiting for the signal to engage in a scorched earth campaign against Taiwanese industrial infrastructure is unlikely to engender that kind of dedicated defense—indeed, surely it emboldens factions within Taiwan that would seek a peaceful reunification with China, or push for immediate capitulation in the case of a war. These may be fine outcomes if they are the preference of the people of Taiwan, but any of them would be fatal to a realist, counter-hegemonic, offshore balancing strategy. Colby is talking tough but in reality undercutting the US position in East Asia.

And it seems increasingly unrealistic to try to disentangle Europe from East Asia. Russia is now receiving North Korean military supplies and has economically survived a punishing sanctions regime with assistance from Chinese firms. The dream of turning Russia against China never made particularly much sense, from a Realist perspective. China and Russia complement one another strategically, with Russia boasting massive reserves of raw materials and a cutting edge arms industry that feed and draw from China’s unmatched manufacturing capacity. Russia’s military occupations of Georgia and Moldova, both dating from before any NATO expansion East, showed a longstanding unwillingness to abandon its imperial goals—and Russia had basically no reason to turn against China, given that it was and is incapable of incorporating Chinese territory into itself or otherwise gaining from such a venture. Moreover, as mentioned above, any effort to limit China’s ability to catch up to or surpass American technological capabilities will require cooperation from European states and firms. This is probably why the Foreign Minister of Taiwan himself, Joseph Wu, has come out in favor of defending Ukraine as a means of defending Taiwan in the future.

What happens next?

Unfortunately, even many self-described ‘national security’ conservatives held their noses and voted for this platform, hoping that Trump and Vance were all talk and, at the end of the day, would follow through on little of it. The beginning of the Trump/Vance administration suggests this is not the case—but admitting a wrong is hard, so expect plenty of Trump-friendly media to try to explain Vance’s foreign policy stances, especially those opposed to Ukraine, as part of a novel Realist strategy. Some will no doubt go so far as to paint remaining Ukraine supporters or ‘National Security voters’ as hopeless idealists still locked in a ‘neo-con’ mindset. But even following the basic principles of Realistic international relations theory, Vance’s positions on Europe and the Middle East are fundamentally backwards, and his hawkishness on Asia is shallow and, in some cases, counterproductive.

Being right, however, isn’t much of a consolation prize when Trump and Vance have such broad powers in the realm of foreign relations. However, both foreign policy liberals and (actual, thoughtful) realists need to keep up the pressure on congress, the courts, and any other relevant venue to make clear that this re-orientation represents neither our preferences as a nation nor a policy direction likely to reap any long term benefit. Moreover, even as Trump and Vance attempt to use the withholding of aid as a weapon to force Ukraine’s capitulation, private donors can go some way to closing the gap, as they have already raised billions for efforts to support and rebuild Ukraine. The United States is unlikely to be taken seriously as a security partner for many years to come, but a civil society response that shows continued support of effective support of allies may help to blunt some of the impact of the wantonly destructive foreign policy that our leaders will be trying to sell as ‘realism’ for the next four years.

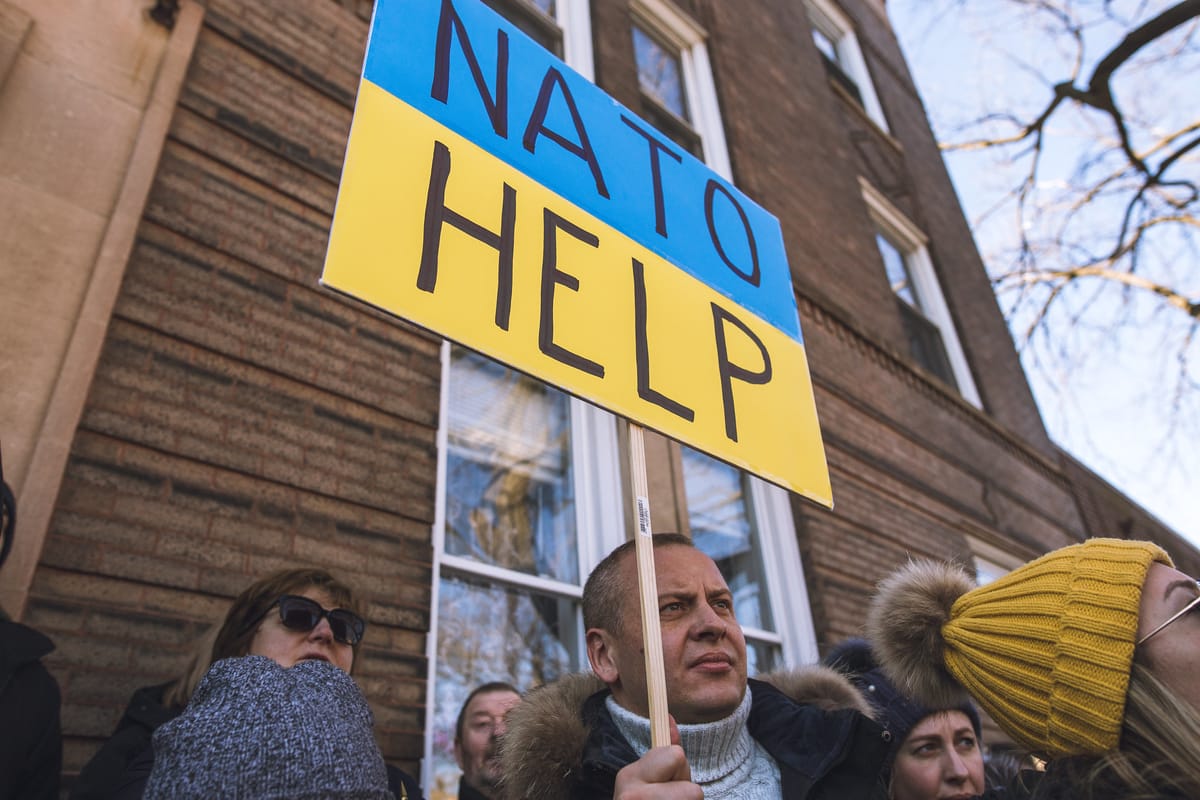

Featured image is February 27 rally in Chicago to oppose the war in Ukraine, by Alek S.