The Crisis of Democratic Governance

State Democrats have failed to deliver what the American people want.

We Democrats like to think of ourselves as the sane and reasonable party, the one with real policy solutions for real problems, as opposed to the madness on the other side of the aisle—100% tariffs, child genital inspections, an invasion of Greenland. This is the reason we treat Trump as having a mandate despite his failure to even win a majority of the popular vote: if they voted for him despite all that, they must really love what he's offering.

The other side of the aisle may very well be mad. But this does not imply that we are sane. After the disaster of the recent election, it's time to take a hard look in the mirror. Is what Democrats are offering in terms of real material policy—our total governance package—that much better than the Republican package?

I'll give you a hint: the answer is no. There is a genuine crisis in Democratic governance. Until we fix it, we will never consolidate the electorate under the liberal banner.

Justice Louis Brandeis once said that American states are laboratories of democracy. One might turn this around for our partisan era, and say instead states are the showroom floors of political parties. Deep red and deep blue states each exemplify what the party stands for—what they would actually do, given consolidated control over government. By that standard, how do the parties stack up?

Consider then the two marquee showrooms for each party's platform, the states that most represent each party in the public mind: California and Texas.

California high school students average 1086 on the SAT; Texas students 971. California's life expectancy at birth is 79, Texas' 76.5. Average hourly earnings in California are $40.24; in Texas they are $33.39. According to the conservative Cato Institute, California is ranked 11th in the nation for personal freedom, Texas dead last at 50th.

So far so good, right? But all of those facts pale in comparison to one: Americans are voting with their feet against blue states. 102,000 people left California for Texas in 2022. In that year Texas saw a net immigration of 175,000 residents . Meanwhile, between July 2021 and July 2022, California saw a net out-migration of more than 400,000 people.

This should be a five-alarm fire in Democratic circles, an inarguable proof of the failure of the Democratic party to deliver what the American people want. Whatever the total package of blue state governance is, people demonstrate that they prefer the total package of red state governance.

Now you might leap up to defend blue states. You might say that actually most Americans want to live in blue states—just look at the surveys! But you can say anything on a survey. The preferences you reveal by your actions are far more telling. For many Americans, their all-things-considered preference is to move from a blue state to a red state.

To understand why we have to talk about some other numbers. The median price of a home in California is $869,000. In Texas it is $349,000. California has a homelessness rate of 43.7 per 10,000 people. Texas—8.3. These numbers are stark.

Housing is the most visible, painful aspect of the crisis in Democratic governance, for housing is fundamental to modern life . Where you live shapes where you work, where your kids go to school, where you spend your free time. For many families, it is the single biggest line-item expense in their budget. And when there is not enough of it—when there is a deliberate, artificial scarcity of it—that distorts and undermines all those activities. California's homelessness crisis is simply the dark mirror of their unending housing crisis

But housing is hardly the only aspect of the crisis. Consider some more numbers. Texas created 274,000 jobs last year. California created 208,000—and California has eight million more citizens than Texas. Texas, home to oil, gas, and cowboys, is also building vastly more green energy than crunchy hippie California. The cost of living in California is 34% higher than average. In Texas it is 7% lower than average. On infrastructure, on green energy, on new factories and new jobs, we Democrats have consistently made it hard and harder to do anything.

It is sometimes said that Democrats don't have the political will to spend money to solve social problems. But money is not the problem. Los Angeles voters appropriated billions of dollars to build housing for the homeless; you only need to look around to see that it hasn't solved the problem. The California legislature appropriated three hundred million dollars for first-time homebuyers, a fund that was depleted in fewer than two weeks by fewer than three thousand people. In New York City, the Second Avenue Subway extension project, underway since 2016, is estimated to cost more than six billion dollars—for about a mile and a half of subway. Money is not the problem. We spend enormous amounts of money to get nothing. An unwillingness to do what's necessary to turn that money into results is the problem. Vetocracy is the problem.

Consider: the crisis of Democratic governance goes well beyond problems pouring concrete. The physical infrastructure necessary for New York City's congestion pricing program was relatively trivial. But from the program's approval to actually activating those cameras took eighteen years, mostly because of "environmental" litigation from New Jersey, but equally an unwillingness of New York to simply do the thing—witness Governor Hochul's bizarre "pause" on the program in 2024.

Let me tell a story from my own neighborhood. There is a busy commercial street; parking is always packed during business hours. The city passed a trial program to allow the Department of Mobility and Infrastructure to increase both the rates and the hours for paid parking on that street and then use the money to perform minor mobility improvements in the neighborhood, like curb repair, daylighting, bus stop improvements, etc.

The department then spent so long simply studying whether they should increase the rates, talking with the community about increasing the rates, etc. etc. that the trial program's legislation came close to expiring. This program involved no physical infrastructure changes, simply updating the programs of parking meter kiosks. And there was no actual lawsuit or any other legal delay. The city was simply afraid to act. They couldn't charge a quarter more for parking without studying, exhaustively, whether this was the definitively right thing to do.

The modern Democratic Party—and the progressive movement generally—is defined by a single, crippling obsession: the fear of power. Democrats lament the perception that we're all talk, no action. But the perception is correct: Democratic politicians talk a lot in highly moralized tones without doing much with the power we're supposedly investing them with. Progressives will lecture you about compassion for the homeless while resolutely opposing measures to build them new homes. Democratic elected officials are content to pat themselves on the back for doing a ribbon-cutting ceremony on twenty units of affordable housing while their city has a deficit of twenty thousand units.

And local housing issues are hardly the only policy arena I might name. Democrats talk about the evils of Putin's invasion of Ukraine—but have we actually committed what's necessary for Ukraine to win? No. Democrats might talk about the suffering in Gaza—but have we actually done what's necessary to bring peace? No. We talk about the rising costs of raising children, of education, of housing, we talk about the climate and green energy, we talk about immigration and about the border. We talk a lot about all of these things, Democratic politicians can't shut up about them. But what have we done about them in the last ten years?

So we are afraid of power. But what is the root of this fear? There are converging ideological and structural factors. Let's begin with the structural ones, which being more material seem more important.

We all know that there are two parties that matter in America, the Democrats and Republicans. We also know that in deep blue or red states, the general election is usually a foregone conclusion: whoever has a D or R next to their name wins, respectively. Therefore, the "real" election is the primary election. Take progressive firebrand Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez. Her election to Congress was celebrated not on November 6, 2018, when the general election was held, but on June 26, when she defeated incumbent Joe Crowley in the Democratic primary.

29,778 people voted in that primary election. 141,122 voted in the general election. 740,963 live in that congressional district. In other words, to win the right to represent three quarters of a million people, it suffices to win the votes of fewer than fifteen thousand committed Democratic partisans—a mere two percent of the total population. This is no shade on AOC personally, who has been an outstanding congresswoman. But it puts into stark relief the structural features of politics in one-party states. Winning elections does not require delivering results for the majority of the actual population: it requires pleasing the fractional minority of people who turn out for the party primary.

Political scientists Bruce Bueno de Mesquita and Alastair Smith distinguish between the nominal electorate and the real "selectorate" whose support is actually necessary to win power. A narrow selectorate inherently warps political incentives away from the needs of the electorate and towards the desires of the selectorate. The dynamic is clearly illustrated by another story from my neighborhood.

A canvasser for a progressive candidate for local city council came to my door. He assured me that the candidate cared about climate change, cared about immigration, cared about abortion. She had all the right stances on all the great issues of the day. Of course, as a councilwoman, she would have power over approximately none of these issues. When I asked about housing the canvasser was caught flat-footed; he mumbled something about ensuring that communities have a say in what gets built. In other words—the status quo. In other words, the "progressive" candidate was promising exactly no material change in city governance. But she said the words that politics-obsessed Democrats like myself want to hear—because she understood that winning power depended on those politics-obsessed Democrats, not the public at large.

I said these structural factors appear to matter most in explaining why the Democratic Party in blue states and municipalities prioritizes signaling to committed Democrats above making material change. But in fact it begs the question of why committed Democrats themselves demand talk over action.

After all, Republicans seem to evince no fear of aggressively deploying state power for conservative ends—and their position in deep red states is structurally identical. But they do not seek community feedback about whether they should do a study to do a study to see if they should ban books about queer kids. They just do it.

To understand the Democratic fear of power, we therefore need to talk about deeper currents in culture and ideology. In particular, we need to understand how deeply the inheritance of the New Left of the 60s and 70s has shaped progressive thinking. So let us wind the clock back to 1968, and see the world through their eyes.

The Cuyahoga River was on fire. Chicago was on fire. Vietnam was on fire. From the New Left's perspective, the System was a great machine of evil that was everywhere grinding up humanity. Robert Moses at home, Robert McNamara abroad. Hence the rallying cry: "do not fold, spindle, or mutilate!" Leftism consisted in stopping the machine from doing its evil work. They wanted to stop "urban renewal" from bulldozing Black communities for the sake of new highways. They wanted to stop the construction of filthy, environment-destroying industries. They wanted to stop the American military from firebombing civilians abroad. In a world full of wicked power, it seemed like fighting power was the only thing that mattered.

Fifty years later we remained consumed with this ethos. We remain obsessed with preventing the state from doing bad things—even as our tools are now mainly used to prevent good things. Environmental laws are leveraged to delay or deny green energy construction. Community feedback is used to block dense housing in rich neighborhoods. Our elected officials prioritize communicating that they have "the right politics" over actually getting anything done. We are all talk, no action.

This gets to the heart of the recent storm of criticism over "the groups" or "the nonprofit industrial complex." For the structural reasons discussed above, these groups have an influence that outruns their actual size in Democratic party politics. And for the ideological reasons discussed above, they're all obsessed not with doing anything, but with obstructing the operations of government while making sad noises about the evils of the world.

So what is to be done? If we want blue states to be our bastions and our showroom floors at once, what must we change?

- Tell the wreckers to pound sand. Groups, staffers, and ideas that prioritize virtue-signaling process over material results need to get kicked out of the tent. This is, first and foremost, a work of culture and ideology. We need to change the definition of progress from "throw your body on the gears" to "build the future."

- Build housing—and everything else. The lack of sufficient housing is the single biggest policy failure of blue states and cities. And the only way to build enough is to reform and remove the thicket of regulations that prevent people from building housing. Enough! It needs to get done.

- Reform the electoral structure. Both of the above reforms—and successful change generally—will be easier to pursue if general elections are more competitive. Competition forces you to perform. It is no accident that purple-state Democrats are more dynamic and energetic than blue state Democrats, as a rule. Multimember proportional elections can be implemented at the state level without going through the federal government.

We need to get our act together. Donald Trump is threatening to invade Greenland and people still voted for him. Democratic states are projected to get hammered in the 2030 redistricting, while Republican states continue to gain. Americans will keep voting with their feet against Democrats and for Republicans until we start actually delivering real material change, not just carefully-worded statements evincing the right kind of concern and deeply held principle.

Let's get to work.

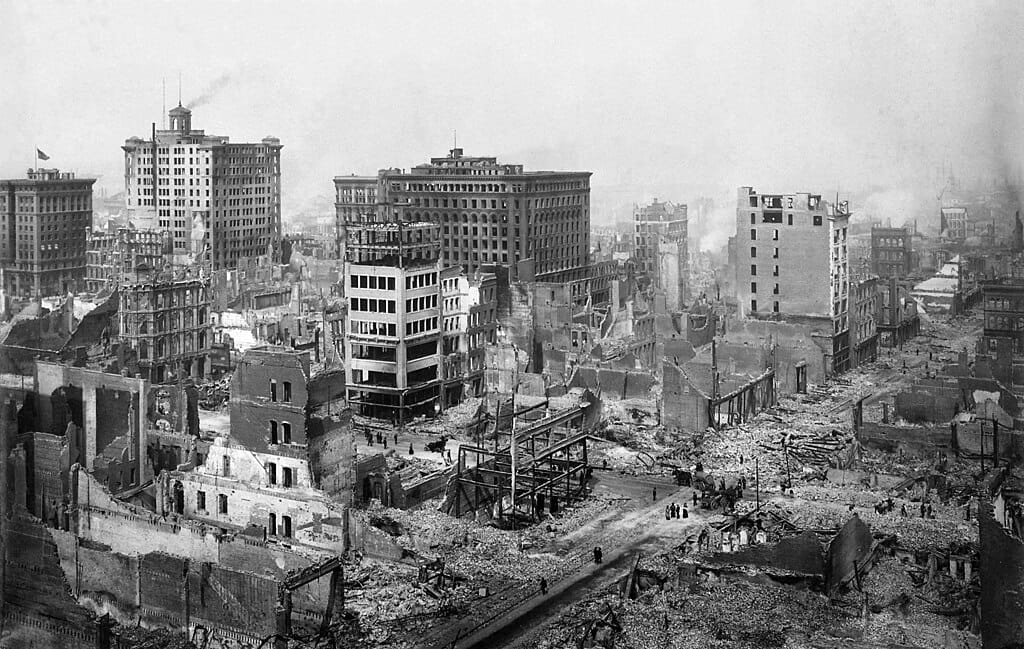

Featured image is San Francisco Earthquake of 1906: Ruins in vicinity of Post and Grant Avenue.