The Banality of Zionism

Zionism is just 19th century nationalism, and its conflicts are ordinary nationalist conflicts.

It’s a sad story. A people, who once had a state and a monarchy of their own, cast down and overrun by foreign invaders. Conquered, oppressed, and disposed, they lost their ancestral homeland, and for centuries lay under the yoke of an alien culture and religion. Finally, in the modern era, they were able to cast off their chains. Through an unspeakably brutal series of wars, they achieved their independence, only to discover that during their long oppression, the land they thought of as the heart of the homeland had been settled by others. Attempts at a peaceful solution failed, more violence erupted, and finally a long, bitter stalemate emerged, one that persists to this day with no internationally-recognized solution.

I am talking, of course, about Serbia and Kosovo.

It’s been well over a year now since the horrific events of 10/7 thrust the Israel/Palestine conflict back into the attention of most Americans, and despite the recent announcement of a ceasefire agreement, the future of the region remains far from clear. Meanwhile, the frenzied discourse it has promoted here at home shows no sign of abating anytime soon. One aspect of this debate that I have found increasingly impossible to ignore, however, is the assumption that there is something unique about this bloodbath, or special, or that it can’t be understood without extensive and exhaustive investigation of the history of the Jewish people. And that’s what I want to push back on today, because I think it’s a huge mistake. Israel looms large in the American cultural imagination, for a number of reasons, and the details of the last seventy years of occupation and conflict are as complex as you would imagine, but in the abstract, this is a conflict that is remarkably banal, one that looks a lot like the results of any other 19th century nationalist self-determination movement.

As a modern political movement, Zionism is often credited to the work of Theodor Herzl (1860-1904), who founded the World Zionist Organization in 1897 and spent his life fighting for the establishment of a Jewish national state. In this, he was far from unique, however—Herzl was a citizen of the Austro-Hungarian Empire, a polyglot patchwork of ethnic and national minorities that was in the process of disintegration virtually his entire life. Herzl was born in Budapest, twelve years after the Hungarian Revolution of 1848 was crushed, and he died in 1904, ten years before the First World War would bring down the venerable Habsburg monarchy. Germans, Hungarians, Poles, Ukrainians, Serbs, Romanians, Croats, Czechs, Slovenians, Slovakians, Italians, Ruthenians, all squabbled and fought for influence, laying claims to historical homelands and national legacies, fighting for a chance to establish or expand “a state of their own”. The problem, of course, was that none of these patrimonies were exclusive.

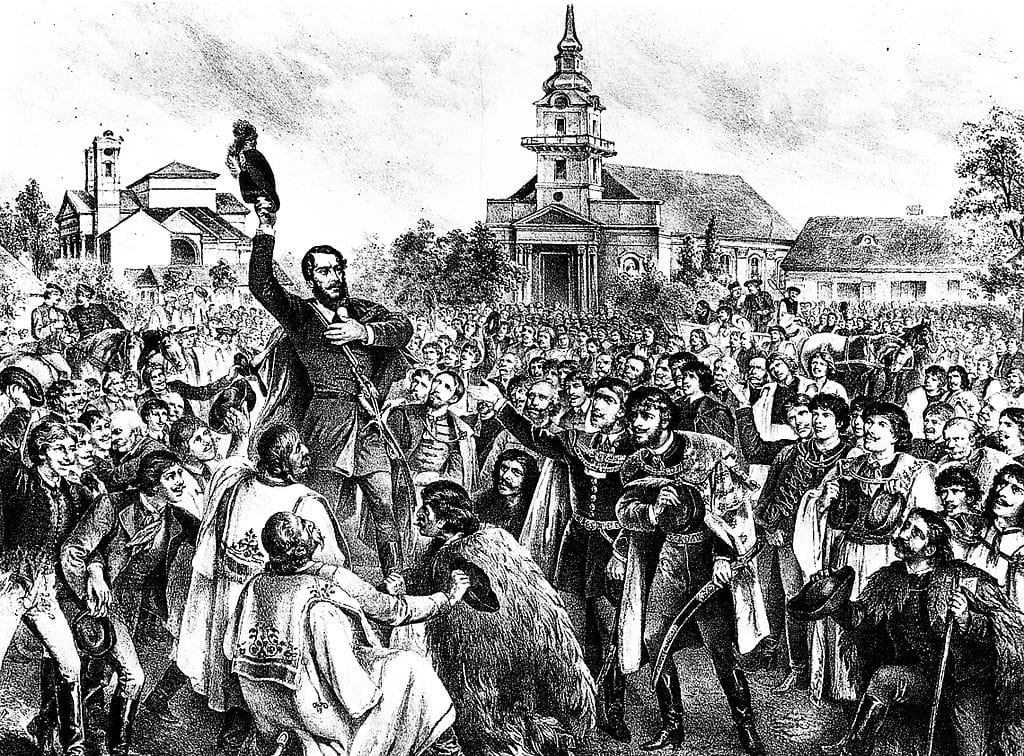

The case of Hungary is perhaps the best demonstration of this. In 1848, Hungarians under Lajos Kossuth had fought for independence from the Habsburgs, seeking to establish an independent state for the first time since the Battle of Mohács in 1526. They had been crushed, and Kossuth had become a hero of European Liberalism. In 1867, Austria agreed to the Great Compromise, offering the Hungarian Kingdom significant autonomy within the Imperial system. But attempts to revive the Medieval Hungarian ‘Crown Lands of St. Stephen’ in a 19th century nationalistic framework soon foundered on the small problem that a majority of people living within were not actually Hungarian, and had little interest in being ruled by Budapest. In Danubia: A Personal History of Habsburg Europe, Simon Winder discusses how this played out in Transylvania:

With the wretched ease of hindsight, it is obvious that the land-grab of 1867 was a terrible mistake for Hungary. Hypnotized by visions of some ancient medieval state and by apocalyptic fears of their own national extinction the Hungarians tried to create a state which was even bigger than Italy and failed. The many Hungarians who lived in Transylvania were in incoherent blocks that could not be put together into anything defensible. Even worse, they were in any event used to living under diverse regimes and with strange neighbors, so even fellow Hungarians could not be relied on in practice to view Budapest’s rule as a plus. (415)

This was an age of “demographic threats”, as countries and ethnicities fought to establish their ancient and undeniable rights to provinces and districts across Central Europe, at the same time that worked to define their very existence, which was often more theoretical than not.

Everyone became obsessed with percentages, with minute census examinations of each county to spot hopeful pro-Hungarian trends. This became a form of panicked timidity. (418)

For Hungary, this experiment in nationalistic imperialism ended in catastrophe, with the defeat of the Central Powers in WWI. The Habsburg Imperium collapsed, and ironically, the Hungarian nationalists who had so long struggled against Vienna found that without it, they were unable to contain their own nationalists. The Treaty of Trianon (1920) reduced Hungary to 28% of its prewar size and 36% of its prewar population, leaving 31% of the ethnic Hungarian population living in foreign states. In his Fourteen Points, Woodrow Wilson had declared that “The people of Austria-Hungary, whose place among the nations we wish to see safeguarded and assured, should be accorded the freest opportunity to autonomous development,” but it was apparent that this was harder in practice than in theory. Self-determination as a principle does not address what to do when not everybody agrees what country they want to be part of.

So, what is the point of this digression? In discussions of Israel and Palestine, I often see a dichotomy proposed, that Zionism is either a racist and colonialist ideology, or “the national self-determination movement of the Jewish people”. What I think is clear, however, from even a cursory examination of history is that these two concepts are rarely disconnected. In demanding a state with a governing majority of Jewish people, Herzl was merely following the zeitgeist, and echoing the demands of his contemporaries. And like them, when it came time for the Jews to actually establish their state, it became apparent that this noble principle did not explain what to do about the people who lived there who didn’t agree.

This quandary came up time and time again over the course of 19th century Europe, as revolutionary activists and theorists fought to forge functional majorities from the demographic cauldron of Europe. Lines on maps, or historic birthrights, rarely matched up to the language or culture of the people actually living there, and the result was endless and endemic violence, as statesmen redrew the map in blood.

Romania joined WWI on the side of the Allies, seeking to gain Transylvania, and Hungary joined WWII on the side of the Axis to get it back. Bulgaria fought four wars in fifty years over control of Macedonia, without success, and Greece and Turkey clashed in the aftermath of the first world war over the Aegean littoral. Serbia lost a quarter of its population in WWI, emerged with domination over a unified Yugoslav state, only to see it collapse into another round of civil war in the 1990s. Amidst the unspeakable atrocities of World War II’s Eastern Front, Poles and Ukrainian militias fought an entirely parallel war, including ethnic cleansings, over control of the Chełm District. In fact, for most of the minor European powers, WWII was simply yet another round of interminable sparring over some border towns that nobody else in the world could find on the map.

Nationalism and liberalism are the two great political forces of the 19th century, both born from the French Revolution, and while they now appear to us often in opposition, they were linked directly for a long time. In Hitler’s Empire: How The Nazis Ruled Europe, Mark Mazower connects the continental ambitions of the NSDAP to the liberal flowering of the Frankfurt Assembly, in 1848:

There was, he argued, no vast gulf separating nineteenth-century German liberals from twentieth-century National Socialists: love of the nation, and hatred of the Slavs, was common to them both. 1848 was the moment when German parliamentary nationalism first revealed its capacity to destroy the peace of the continent. No longer could political differences be adjusted solely among kings and diplomats for now they involved the aspirations of entire peoples—aspirations increasingly defined in terms of land, language, and blood(. . .) ’Are half a million Germans to live under a German government and form part of the great German Federation, or are they to be relegated to the inferior position of naturalized foreigners only?’ (15-16)

Self-determination was a powerful motivator, and the logic leading to war was inarguable, in far too many cases. If every people had a right to a state and a nation of their own, then anyone impeding on the right—whether that was Czechs in the Sudentland, Macedonians in Vardar, or Palestinians in the West Bank—was an existential enemy. Of course, the reverse was true as well, leading to farcical wars of words throughout the 19th century, as national intellectuals strove to find deeper and more authentic roots than their rivals. Serbs and Croats fought over which band of Slavic ancestors had settled in which valley first, while Hungarians and Romanians sought inspiration from further afield. Returning to Danubia:

It was however attractive in bolstering Magyar self-identification with Central Asia and providing fresh grounds for the burgeoning relationship between Budapest and first Ottoman and then Kemalist Turkey, a relationship which set aside centuries of mutual hatred in favor of a more nurturing, shared hatred for the Russians. This cult of Central Asia (‘Turanism’) was to rebound somewhat by refining a magnificent weapon for the Romanians, who went on entertainingly about the Magyars being merely ‘Asia’s discharged magnates’, whereas they themselves were the pure outpourings of Trajan’s centurions’ loins and the true gatekeepers of European civilization. This unhelpful debate has never been settled. (386-387)

I think that anyone who has spent time engaged in discourse over the Israeli Occupation will recognize these lines of argument. Long digressions about the Twelve Tribes of Israel and litigation of the historicity of the Exodus mythos, appeals to the Bar Kokhba revolt and the destruction of the Second Temple, endless lists of anecdotes about which tribe of proto-monotheistic semitic nomads first settled in Canaan and when, none of which would seem to have much bearing on whether it is acceptable for a modern state to deny 33% of its population self-government or self-determination based on ethnicity.

This can be almost comical in its absurdity, as when Macedonia was forced by Greek pressure to rename itself ‘the Republic of North Macedonia’ in 2018, due to claims by Athens that the name was an appropriation of Greek culture and amounted to an attempt to exert claims over the territory of Greek Macedonia, which is unrelated linguistically or ethnically. But in Israel, history remains as sharp a weapon as it ever has, with the Israeli government and its partisans demanding the right to rule over the Palestinian minority of East Jerusalem, the West Bank, and Gaza based on tendentious claims to historical continuity. In response to a ruling by the International Court of Justice this year ruling the Israeli Occupation illegal under international law, Prime Minister Netanyahu responded: “The Jewish people are not occupiers in their own land, including in our eternal capital Jerusalem nor in Judea and Samaria, our historical homeland. No absurd opinion in The Hague can deny this historical truth or the legal right of Israelis to live in their own communities in our ancestral home.” This is a claim by right of blood and soil, by right of conquest, one that the delegates in Frankfurt in 1848 would have recognized easily.

'Our right is that of the stronger, the right of conquest……legal rules appear nowhere more miserable than where they presume to determine the fate of nations.’ (16)

The central conflict we see over and over again—where multiple nationalities lay claim to the same peoples and provinces—trends inexorably towards a simple solution. Prewar and interwar Central Europe witnessed incessant fights over languages and schooling, as dominant ethnicities tried to forcibly assimilate their neighbors, and minorities carved out their own cultural and social spheres. When that failed, the logic of ethnic cleansing and population exchange invariably asserted itself. In 1923, Greece and Turkey cemented peace by exchanging 1.2 million ethnic Greeks from Asia Minor for 350,000 Muslims from mainland Greece. In 1940, 100,000 Romanians and 60,000 Bulgarians were uprooted as part of Bulgaria’s annexation of the Southern Dobruja. Between 1943 and 1945, Ukrainian militia of the OUN-UPA killed between 60,000-120,000 Poles in Volhynia and Eastern Galicia, in an attempt to ensure that the region would remain part of Ukraine following the war. And in a grand culmination, the Allied authorities at the Potsdam Conference signed off on the ethnic cleansing of 12 million Germans from Eastern Europe, a ruthless response to the Third Reich’s use of ethnic German minorities as a justification for expansion and intervention. In this context, ‘the Nakba’, the Israeli expulsion of 750,000 Palestinians in 1948 as part of a deliberate plan by the new government to cement a Jewish demographic majority, appears unusual only in how late it occurs. In all other ways, it is a textbook application of pre-WWII Central European nationalism, as was the mass exodus of 900,000 Jews from the Arab world that occurred in the following years.

So, what are we to take away from all of this? Seeing Israel and Palestine in the context of ethnonationalist liberation does not automatically provide an easy solution, nor does it remove the complexity of navigating decades and decades of conflict, occupation, and bloodshed. But I think it’s important to take a step back, and realize that everything we are seeing here is something we’ve seen before.

Zionism is racism, in the same way that the Risorgimento or the Srpski Preporod were; nationalism emerges out of the same ideological ferment that produces scientific racism, fascism, and ethnic cleansing; national self-determination is often both justified and necessary, but it's not an inherently good process. The Zionist project succeeded, in the same way that the Romanian and Serbian and Italian national projects succeeded. That doesn't make Israel's existence inherently good or evil, it's just a historical fact, one that has benefited some and devastated others. This is not unusual, if anything, it is the story of most 19th and 20th century history and the breakup of the old dynastic empires.

Zionism is the national self-determination movement of the Jewish people, as well as a force for ethnic cleansing, racial apartheid, and genocide, which makes it just like every other national self-determination movement. You should look at the Tomb of the Patriarchs the way you do Blackbird's Field, you should think about Judea and Samara with the same reverence you hold the districts of Baranja, Bačka, Međimurje, and Prekmurje, care about the Eternal and Undivided City of Jerusalem as much as you do the Megali Idea.

These are not unique problems, sprung from some unsolvable quagmire of ancient hatred, they are the inevitable result of any project of national self-determination. And if you wish to build something not predicated on violence and segregation, you are going to have to try and transcend that.

The grim truth about Israel that no one wants to admit is that it's banal. Jews aren't the Great Satan, and we're not the Chosen People. Israel isn’t the Villa in the Jungle or the cornerstone of the American Empire. We're just human beings, and we act mostly like other human beings.

That’s the problem.

Featured image is Lajos Kossuth's recruitment speech on 24 September 1848, by Franz Kollarz