Representation Matters

It’s not enough, but without it, there’s only segregation and extermination.

In her 1986 book Our Dead Behind Us, poet Audre Lorde responded acidly to the backlash of the Reagan era in a poem titled “Equal Opportunity.”

The American deputy assistant secretary of defense

for Equal Opportunity

and safety

is a home girl….

The moss-green military tailoring sets off her color

beautifully…

Superimposed skull-like across her trim square shoulders

dioxin-smear

the stench of napalm upon growing cabbage…

“as you can see the Department has

a very good record

of equal opportunity for our women”

swims toward safety

through a lake of her own blood.

Lorde was writing at a time when the Civil Rights Movement had successfully restored voting rights to many Black people in the South and the North; as a result the number of Black politicians in the US had risen dramatically. In March 1969 there were 994 Black men and 131 Black women in elected office; six years later, in 1975, the number was 2969 Black men and 530 women.

Yet, even as those numbers continued to rise, the conservative Republican government largely abandoned any momentary commitments it had had to nationwide egalitarian antiracist policies. Austerity policies devastated Black communities, leaving them with no employment opportunities, few educational opportunities, and no hope. Mass incarceration ramped up—there were 330,000 prisoners nationwide in 1980 and 771,000 at the end of 1990, a 134 percent increase. Those prisoners were disproportionately Black. More, as Lorde’s poem chronicles, the US continued to use its military might to bully and intervene in nations like Grenada, which Reagan invaded in 1983.

In that context, as Lorde says, the push for diversity and representation could seem like a bait and switch or an outright boondoggle. What was the point in having Black people in positions of authority if they pursued the same policies of racism and policing? Lorde was very aware that Woodrow Wilson Goode Sr, the first Black mayor of Philadelphia, was in office when Philadelphia police bombed homes of the separatist Black group MOVE, killing 11 people, including 5 children.

Lorde’s poem still resonates 40 years later; Clarence Thomas and Eric Adams are not liberating anyone. Tokenism doesn’t necessarily change policy, and having a seat at the table is not helpful if you are just there to chew and serve the same rotten food.

At the same time, though, in the early days of the Trump administration, we are seeing an all-out assault on even limited forms of representation—an all-out assault which is serving as an ugly reminder of why people fought so bitterly, and for so many years, to get those seats, even when they could clearly see the problems with the menu. Lorde isn’t wrong. But given where we are, it’s worth reiterating the reasons that representation is a necessary, if insufficient, condition for justice and equality.

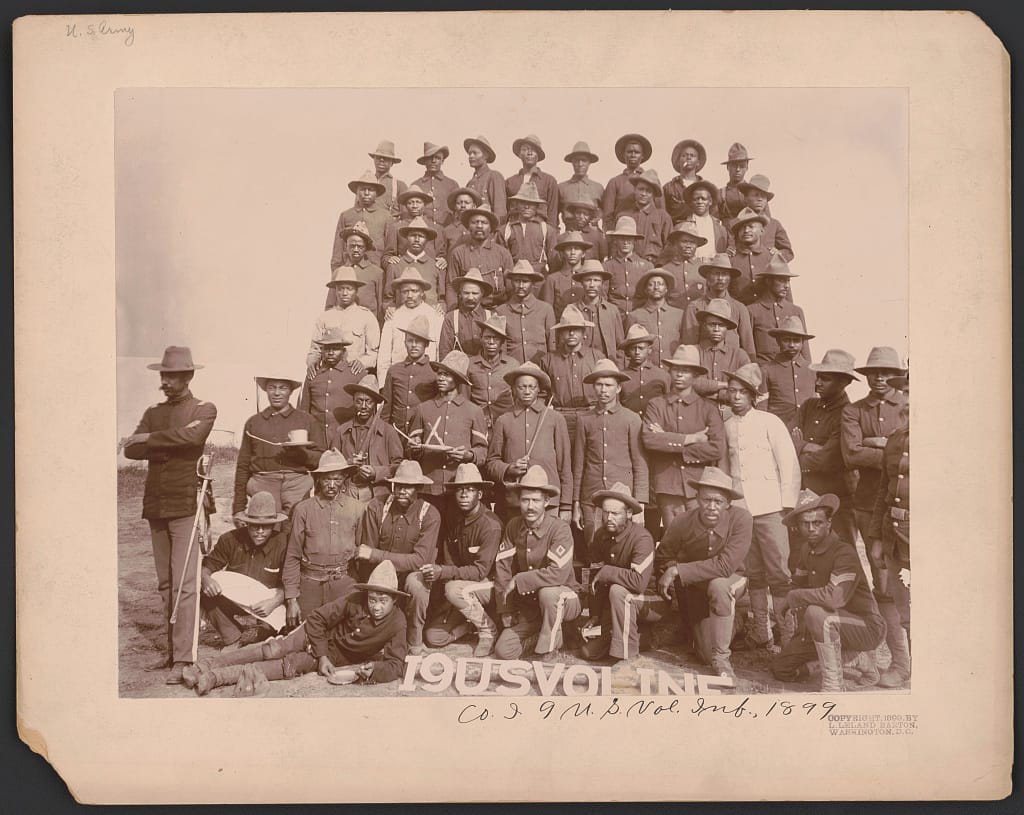

Black troops and gay marriage

Civil rights organizations and movements have long been aware of the importance of representation and visibility. In particular, as Lorde’s poem points out, advocates have often focused on representation in military service as a way to emphasize belonging, patriotism, presence, and ultimately humanity.

During the US Civil War, abolitionists like Frederick Douglass pushed the Union government to allow Black soldiers to fight. Black soldiers faced ugly conditions and persistent racism; they were not allowed to serve as officers in their own regiments, and if they were captured by Confederate forces they faced re-enslavement or execution. Nonetheless, Black troops signed up both because they believed defeating the Confederacy was vital and because they believed it was important to show people everywhere in the country that Black people were honorable, brave, patriotic, and capable.

In both goals, Black troops were successful. The commander of the first Black regiment, which fought in South Carolina, said his troops, “fought with astonishing coolness and bravery and deserve all praise.” Another Union Captain said that while many white people thought Black people their inferiors, “a few weeks of calm unprejudiced life here would disabuse them, I think—I have a more elevated opinion of their abilities than I ever had before.”

W.E.B. Du Bois noted that Black labor had not been respected, and that Black petitions and eloquence in the cause of freedom were laughed at. But when Black people "rose and fought and killed the whole nation with one voice proclaimed him a man and brother.”

Du Bois’ statement there is obviously an exaggeration; Black troops during the war continued to face entrenched and vicious prejudice, as do Black people today. But military service during the Civil War played an important role in solidifying Northern support for emancipation and for citizenship.

Another, less martial, example of the power of representation is the campaign for marriage equality. Support for gay marriage famously skyrocketed in barely a generation. In 1996, 68% of the public opposed gay marriage and only 27% supported it. In 2012, 53% of the public supported marriage equality, and only about 45% opposed. Today the number is 69% in favor and 29% opposed—almost an exact reversal of the status of public opinion thirty years earlier.

Advocates achieved the turnaround in public opinion through a hard fought, carefully calibrated combination of lawsuits and public outreach. Conservative backlash was fierce, and many LGBT people and organizations also questioned whether marriage equality was the most important, or the most winnable, cause for the community. Today, though, most agree that by carving out some jurisdictions where gay marriage was legal, advocates were able to make lesbian and gay married couples much more visible and much more acceptable.

“So many people have friends and family who are LGBT who are more comfortable talking about it now,” as one gay married Missouri man said in 2014. “[They say,] ‘If I can enjoy the trials and tribulations of marriage, why shouldn’t my son or daughter or my brother or sister or my friend or neighbor be able to do so as well?’”

The new Trump segregation

Lorde and others have understandable reservations about integration into institutions like the military, or marriage or the police. But Trump is demonstrating that when the government sets itself against representation as representation, the result is extremely ugly.

Trump has issued an executive order terminating all DEI (Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion) programs in the federal government. He’s also targeted DEI initiatives for federal contractors and grantees.

The constitutionality and legality of Trump’s orders has been challenged, and lawsuits are already ramping up. Practically, though, the assault on DEI programs has already led to a sweeping effort to resegregate the federal government. The Army and Navy removed webpages highlighting the contributions of women service members. The National Institute of Health has removed images of women scientists and scientists of color. The NFL removed an “End Racism” banner from its end zone for the Super Bowl, in order to avoid offending racist-in-chief Donald Trump.

These are not just cosmetic changes. Erasure of representation goes along with elimination of resources. Researchers are concerned that Trump’s opposition to research by or for anyone who is not white could result in the termination of grants to combat HIV and malaria in low-income countries. The pause on funding for USAID is expected to ensure that tens of thousands of babies contract HIV.

As another nightmarish example, National Center for Missing & Exploited Children (NCMEC) has been told to eliminate any reference to LGBT issues from their materials or face a loss of federal funding. Journalist Marisa Kabas says “Staff were told they need to deadname trans kids in their reports to comply.”

LGBT youth are especially vulnerable because of parental prejudice and abuse; 28% experience homelessness or housing instability,and that jumps up to close to 40% for trans youth. The Trump administration is demanding that the organization tasked with helping homeless youth, participate in harassing and abusing many of those young people. In this case, erasing visibility is likely to lead to actual deaths.

We need to reiterate the obvious

Many of the arguments here may seem obvious or uncontroversial. Segregation is bad. Forcing LGBT youth into the closet is bad. Refusing to fight malaria because the people who suffer from it are disproportionately nonwhite and poor is monstrous.

And yet, unfortunately, the people in charge of the country right now are pro-segregation, pro-erasure, and pro-closet. As Audre Lorde reminds us, it’s important not to see representation as the final goal, or as a substitute for real freedom and justice. But we also need to recognize that the reactionary roll-back of representation is a deliberate attack on equality, and on all marginalized people. Representation in the military, in pop culture, in government, even in bullshit corporate mission statements—it all creates a baseline expectation of acceptance, or at least of presence, in public life.

The alternative to that baseline is segregation, discrimination, and, ultimately, extermination. “What we must do,” Lorde wrote, “is commit ourselves to some future that can include each other and to work toward that future with the particular strengths of our individual identities. And in order for us to do this, we must allow each other our differences at the same time as we recognize our sameness.” Trump does not want to allow anyone their differences. Unless he’s stopped, that means that for those who he considers different, he will attempt to erase first their representation and then their lives.

Featured image is Co. I, 9 U.S. Vol. Inf., 1899