Patrick Deneen Fails to Understand the Liberal Tradition

A review of Patrick Deneen's Regime Change: Toward a Postliberal Future.

With the end of the Cold War conservative consensus, the rise of an alternative political foundation for contemporary conservatism has risen to the horizon. Much like the conservative revolutionaries that could be found in Interwar Europe, many self-proclaimed conservatives today have given up on committing to the liberal democratic framework and are instead calling for the rise of an illiberal political form that is more muscular and capable of crushing their political enemies. This shift in conservative foundations and values has been a global one—beyond the rise of Donald Trump and the MAGA movement in America, many national conservatives and post-liberals today fantasize about creating a state similar to Hungary under the rule of Viktor Orban, Poland under the rule of the Law and Justice party, or Russia under Vladimir Putin’s reign. What these new right populist movements all have in common is the common focus on an us-vs-them approach to politics, a claim to be the only authority capable of combating “degeneracy” and moral decline, and the use of force as a tool to “educate” the culture to move in ways preferred by the new right populists.

Patrick Deneen has sought to be the theorist of this post-liberal and national conservative movement. Deneen is a professor of political science at the University of Notre Dame. Deneen’s intellectual trajectory serves as a useful reminder of the evolution many other national conservative thinkers have also taken in the Trump years. Before Regime Change, Deneen was known for his acclaimed book Why Liberalism Failed in 2018, and 2005’s Democratic Faith. Both of these works laid the roots for the evolution of his intellectual thought in the 2010s; Deneen evolved from a critic of democratic perfectibility to one of liberalism in general. One element that’s remained consistent throughout his critiques has been his suggestion that liberalism degrades the basis upon which it relies, whether it be community (as described in Why Liberalism Failed) or the environment (his blog posts urging panic over the peak oil theory).

Deneen thus is a member of a crop of political thinkers who have not merely taken up the mantle of justifying a new sort of right-wing theorizing after the victory of Trump, but have been thoroughly transformed in their own vision of the world by it. Theses about a right-wing “withdrawal” from the broader world, exemplified by Rod Dreher’s “Benedictine communities” and animated by the spirit of an older, libertarianism-inflected tradition of voluntarism have been replaced by a grander vision of total overthrow of the contemporary liberal order. Deneen’s latest book is a paradigmatic example of this development in radical right thought, its name not deigning to hide its ambitions: regime change. A striking, eye-catching proposal. The rhetoric suggests not a call for voluntaristic withdrawal from contemporary society nor a mere transfer of governmental power to right-wing hands, but rather a total revolutionary uprooting of the contemporary social order.

The project

Deneen’s target in this radical project is what he perceives to be a hegemonic liberalism that appears to animate every section of American life. Some of Deneen’s claims are repetitions of what political theorists have known to be standard fare in critiques of liberalism for a long time: its ignorance of the common good, abstract individualism and denigration of culture for consumerist excess. Deneen’s claims that the American right-wing (and a large portion of the global right) are part-and-parcel of the liberal order are not innovative claims by any measure either. What is innovative about Deneen’s book is the idea that liberalism in all its forms is characterized by a sort of bureaucratic elitism. There are subtle differences in Deneen’s understanding of liberalism’s elitism as compared to that of radical democrats like Chantal Mouffe; while the latter emphasize the necessity of an agonistic counterweighting of popular democracy to liberal elitist constraints on popular sovereignty, Deneen believes that liberalism severs the elite from its organic incorporation into a “polity” that it shares with the “ordinary people.”

Borrowing from Aristotle, Deneen describes the key feature of this polity as a “mixed constitution” defined by “blending.” In broad strokes, blending appears to involve the integration of the aristocratic elite and the common people in one harmonized society, as opposed to the conflictual politics of either Marxism or liberalism, where either the elite or the people are placed in perpetual opposition to their other. The exact details of this remain unclear, but the fourth chapter, “The Wisdom of the People," gives signs as to what exactly this would mean. Deneen approvingly cites Burke’s vision of the conservative order as one where an institutional and aristocratic elite places sufficient “restraint” on the passions of the people, while reflecting at the same time the “popular consent” of the people for intergenerational traditions that have been passed down from elders to the youth.

Of course, in order to define a positive conception of the elite and the commons, Deneen must define what he considers to be its negative contemporary manifestations. The elite, under liberalism, appears to be the “laptop class.” This is an amorphous collection of Never-Trumpers, campus liberals, college professors who promote Neo-Marxism (distinguished by Deneen from traditional Marxism, as a result of the new variant’s promotion of such anti-traditional forms of thought like critical race theory or critical theory), Silicon Valley professionals, “woke capital” (he does not clarify who could be included here), and all those prone to supporting liberalization of traditional socio-cultural mores. Opposed to these are the salt-of-the-earth coalition of workers and small business owners (but only those who follow Deneen’s conception of right-communitarianism, one would have to imagine. The rest are elites.) To Deneen’s credit, he doesn’t provide a simplistic Manichean understanding of these groups: he is quite clear that the contemporary commons are given to an uneducated populism which manifests itself in the election of immoral figures such as Donald Trump. Nevertheless, Deneen believes that the degradation of the commons is attributable to the elites in the last resort. In one word, we can characterize contemporary elites as “woke.” They promote an ideology that breeds suspicion, emphasize meritocratic competition that destroys social bonds, and generally see themselves as above the disgusting proles. In the name of an abstract egalitarianism, these Deneenian elites end up doing nothing but entrenching their own elite status, coded as being better than the commons in performing elite ideology.

As noted above, this negative conception of elite-commons relations stands in opposition to Deneen’s understanding of a polity defined by “blending.” There isn’t a clear pathway to how he would reach this state of polity, outside the claim that it would involve “Machiavellian means” towards “Aristotelian ends.” However, he does provide a laundry list of policies that he would like to see implemented in his ideal society. These are all to be exercised by an apparently multiracial, working-class polity that would also simultaneously lead to the rise of an elite that understands its role as the “supporting and elevating the common good that undergirds human flourishing, are worthy of emulation and, in turn, elevates the lives, aspirations, and vision of ordinary people.” This is what he calls “aristopopulism.” These policies include a vast increase in the number of representatives in the U.S. Congress to increase popular representation, adding members of the commons such as farmers and wage-workers to the Federal Reserve’s Board of Governors in order to represent popular interests in monetary policy, breaking up Washington D.C. and redistributing government agencies and departments to smaller, struggling cities to dilute the power of contemporary urban elites, destroying the power of universities in American cultural life, the refoundation of American manufacturing (though interestingly Deneen is critical of tariffs), and heavy cultural censorship of what Deneen perceives to be immoral media (like pornography and media that appears to promote “libertinism” and denigration of religious belief). More extravagantly, Deneen conceives of a cultural policy that works towards the promotion of civic virtue, though this policy remains defined merely in opposition to the perceived degeneracy and elitism of contemporary popular culture.

Finally, in a critique of liberal meritocracy and communitarian notions of society, Deneen turns towards advancing his own understanding of the American project based on solidarity. In Deneen’s understanding of this solidaristic project, borrowing from the Puritans and the Anti-Federalists, public good dominates totally over private interests, inequalities in distribution are organized such that they are for the benefit of the public good, and freedom is only the freedom to act according to the constraints of virtue.

All this, then, contributes to Deneen’s critique of liberalism, elitism and contemporary American culture. Does any of it make sense, though?

Misunderstanding Machiavelli

The first part of Deneen’s story that does not pass the sniff test are his strange interpretative claims. For one, Machiavelli doesn’t make a clear distinction between the means and the ends that he seeks to attain. Indeed, in the Discourses (Disc.III.9.2), Machiavelli’s understanding of the necessity of his princely means is to allow for reflection of the diversity of public interests. Furthermore, as the critique of the French system illustrates, Machiavelli distinguishes the fully constitutional regime that is his end from a minimally constitutional regime like that of royal France, holding that the latter system inevitably falls into decline as a result of the lack of popular sovereignty in armaments associated with minimally constitutional regimes (Disc. II.30.2) (France being held as the ideal type of a non-republican regime by Machiavelli, as shown in Disc. III.1.5). Further proof of the fact that Machiavelli does not see a proper distinction between means and ends is provided by his commentary on the conflict between plebs and nobles of Rome as being causal of the liberty they possess, as opposed to merely being something that can be extricated from the republican project of Rome in order to foster civic virtue through other means. The upshot of Machiavelli’s understanding of “means” is that he is radically critical of the notion of the common good itself, seeing it as antithetical to his understanding of human nature as naturally self-interested. If that is not all, Machiavelli rejects notions of civic friendship and sociability that Deneen seems to rely on, noting that such reliance on solidarity does nothing but reinforce structural inequalities between classes (this position is elaborated upon further in Warner 2018). What Deneen’s claiming of Machiavellian means appears to achieve then is not support for common-good conservatism, but a fundamental critique of the possibility of its internal parts: if common good itself is nothing but an ideological mystification used to reinforce inequality as Machiavelli holds, and man is incapable of solidarity outside his own self-interest, no Deneenian conservatism proceeds.

Misusing Tocqueville

Further problems arise in Deneen’s interpretation of Tocqueville, whom he holds to be a kindred spirit. Certainly, Tocqueville praises localist democracy in the American and even specifically New England mode that Deneen appears to hold in high regard. Nevertheless, Tocqueville remains suspicious of that very same local democracy’s tendency towards mob justice and racial discrimination. In Democracy in America, he recounts “the inhabitants of a county, where a great crime had been committed, spontaneously form committees for the purpose of pursuing the guilty party and delivering him to the courts…In America, he [the criminal] is an enemy of the human species, and he has all of humanity against him.” Of course, within the context of the passage, this statement might not seem as incongruent with Deneen’s interpretation, for Tocqueville apparently praises the requirement for provincial institutions and aristocracy in order to hold back these elements of mass participation. However, Tocqueville’s logic of association is decidedly non-aristocratic: the association in Tocqueville isn’t presented as a “mixing” of elite and masses, but as a pluralistic counterweight to governmental power in the absence of natural aristocratic elites. Once again, like Machiavelli, Tocqueville’s associational life is specifically agonistic and conflictual. As Mark Reinhardt’s work astutely notes, the “point is not only political incorporation but political contestation.” In Deneen’s work, there is no place for this contestatory element so essential to Tocqueville, for his mixing is self-complete and purely dialogical in the interaction between its parts. Of course, perhaps, the more radical problem in Deneen’s appropriation of Tocqueville for his “aristopopulist” project lies in the fact that Tocqueville sees a difference in kind between the sort of aristocratic society whose end he lamented and the new democratic society of today. To quote:

No man, upon the earth, can as yet affirm absolutely and generally, that the new state of the world is better than its former one; but it is already easy to perceive that this state is different. Some vices and some virtues were so inherent in the constitution of an aristocratic nation, and are so opposite to the character of a modern people, that they can never be infused into it; some good tendencies and some bad propensities which were unknown to the former, are natural to the latter; some ideas suggest themselves spontaneously to the imagination of the one, which are utterly repugnant to the mind of the other. They are like two distinct orders of human beings, each of which has its own merits and defects, its own advantages and its own evils. Care must therefore be taken not to judge the state of society,”which is now coming into existence, by notions derived from a state of society which no longer exists; for as these states of society are exceedingly different in their structure, they cannot be submitted to a just or fair comparison. It would be scarcely more reasonable to require of our own contemporaries the peculiar virtues which originated in the social condition of their forefathers, since that social condition is itself fallen, and has drawn into one promiscuous ruin the good and evil which belonged to it.

The philosophical anthropology underlying Deneen’s reactionary conservatism, then, is rejected by Tocqueville himself. Deneen’s attempt to appropriate Tocqueville as an aristopopulist looks further grimmer when one turns to Tocqueville’s famous analysis of race in America, which Deneen conveniently ignores in its entirety. Tocqueville understands not only the American South, but also the North to be defined by a structure of racial privilege. To elaborate, Tocqueville analyzes the state of African Americans sui generis (and not merely slaves) as well as Indigenous subjects of the United States in a manner that would appear to many as close to the analytical mode of critical race theories.

In Tocqueville’s analysis, the African slave is deprived of rights even before he is born, “before he began his existence.” The African slave, “devoid of wants and of enjoyment, and useless to himself learns, with his first notions of existence, that he is the property of another” and experiences his entire subjectivity first and foremost as slave: a total state of social death as a result of exclusion from white “humanity.” And as if to heighten the stakes, if the slave “becomes free, independence is often felt by him to be a heavier burden than slavery; for having learned, in the course of his life, to submit to everything except reason, he is too much unacquainted with her dictates to obey them.” Once again portraying his modernity, Tocqueville notes the effects not only of social death but its impact on African American lives even outside the context of slavery, i.e., structural racism. To drive home the point, freed slaves and

those born after the abolition of slavery [emphasis of the writer], do not, indeed, migrate from the North to the South; but their situation with regard to the Europeans is not unlike that of the aborigines of America; they remain half civilized, and deprived of their rights in the midst of a population which is far superior to them in wealth and in knowledge; where they are exposed to the tyranny of the laws and the intolerance of the people. On some accounts they are still more to be pitied than the Indians, since they are haunted by the reminiscence of slavery, and they cannot claim possession of a single portion of the soil: many of them perish miserably, and the rest congregate in the great towns, where they perform the meanest offices, and lead a wretched and precarious existence.

Even the vaunted anti-slavery North is castigated by Tocqueville for its complicity in a racism that runs deeper than anything that can be solved by simplistic anti-discrimination diktats.

Of course, Deneen does not deny the existence of systemic racism, and even claims that many dominant social concepts are in fact functionally complicit in the perpetuation of this racism. And certainly, he never explicitly marshals Tocqueville for his arguments about racism. But in Deneen’s understanding of elite liberalism, systemic racism is a product of a liberal order that evidently separates the working class along racial lines, and it is here that it is important to note that Tocqueville himself rejects this understanding of the racial divide that he finds basic in American society. Tocqueville is in fact explicit: “The entire white race constituted an aristocratic body headed by a number of privileged individuals” and “leaders of the American nobility perpetuated the traditional prejudices of the white race in the body they represented.” Not only does the white race constitute as a whole in the prevailing ideology of American racism as a caste other than its others, it is the traditional customs of the white race (and specifically the aristocratic ones!) that Deneen so vaunts that serve as the marker of this degradation. After a closer, more reasoned textual reading of Tocqueville, is it possible to agree at all with Deneen’s use of him for his “aristopopulist” project? Even in the details the source contradicts its epigones.

Basic failures of intellectual history

Thirdly, moving on from Tocqueville, Deneen’s understanding of the history of the mixed constitution is flawed. Whatever the virtues of his analysis of Locke, Deneen’s attribution of the beginnings of contemporary liberalism to him is difficult to sustain. Locke’s concerns with toleration do initiate a particular problematic, but the history of that problematic has directions much closer to what Deneen himself believes to be superior to atomistic liberalism: that of the mixed constitution. As Chinatsu Takeda helpfully points out in her analysis of French political liberalism in the early 18th century, luminaries such as Germaine de Staël were in fact deeply concerned with the notion of “mixing” between an aristocratic center and a democratic periphery (Takeda 2019, 115). Furthermore, KS Vincent (Vincent 2011, “Introduction”) points out that this tradition of “French pluralism” was not just embodied by de Staël, but by collaborators such as Benjamin Constant and the Coppet Circle, who in turn borrowed from an older tradition with multiple sources such as Montesquieu (curiously unmentioned in Deneen’s book). Though this form of mixed liberalism appears alien to us today, its maintenance of a peerage that could mediate between the capital and the regions is in fact the strand in French political liberalism that Tocqueville picked up. But the problem of history goes even deeper than that of French liberalism. It was the liberal German economist Friedrich List who pioneered the argument for municipal autonomy and associational democracy to satisfy the needs of individuals embedded in communities without resorting to centralized state intervention. Deneen lambasts liberals for ignoring tradition, but he himself appears to be wildly ignorant of the tradition that he aims to critique. In fact, one is hard-pressed to find any of the more recent literature that contextualizes Tocqueville within his intellectual context cited in Deneen’s work. Annelien de Dijn’s seminal work on how Tocqueville embodied a French tradition of “aristocratic liberalism,” for example, does not find a single mention in Deneen’s entire work. Maybe Deneen is creatively appropriating intellectual history for his own purposes here, but it is difficult to say how successful he can possibly be at doing this when the sources of his thought are actively resisting his narrative of counter-liberalism at every turn.

A final problem appears in Deneen’s egregious misreading of John Stuart Mill. Deneen claims that Mill’s critique of mere tradition should be read as fiat for those who want to engage in “experiments of living” free of the constraining power of handed-down customs. One can only be compelled to suggest that Deneen reread the third chapter of Mill’s On Liberty, where he undertakes a sustained discussion of the work of Wilhelm von Humboldt’s notion of bildung. Not only does Deneen ignore Mill’s positive appraisal of the role of customs and traditions in the cultivation of the intrinsic teleological capacities of man qua man, he straightforwardly ignores most of Mill’s actual critique of slavish adherence to past customs. With astounding self-confidence, he declares that from “another view” Mill might be wrong, without providing any rigorous argumentation for it. Misunderstanding a thinker is one thing, but simply not engaging with their thoughts is an even greater flaw.

A delusional history and present

Even beyond Deneen’s failed engagement with other thinkers working in political theory and philosophy, there remain quite a few issues with Deneen’s critique and proposed polity. As mentioned earlier, Deneen proposes an cross-institutional alliance of postliberal elites and conservative populists in order to establish his desired polity, but where Deneen fails is elaborating on a means by which to ensure postliberal elites desire to pursue the common good instead of their self-interest. To get around this, Deneen appeals to a sense of tradition, stability, and custom that is common to both the postliberal elite and the conservative populist movement that will produce a moral economy in which all participants involved constrain themselves in a form of cross-class solidarity/corporatist arrangement. One such appeal Deneen makes as a sort of historical example of how to incorporate virtue into one’s elite/aristocratic class is the Renaissance-era “Mirror of Princes,” but it strains both historical and logical credibility to believe the social process that was capable of producing the Borgias and other such leaders was somehow more successful in the moral formation of its elite class. Also, given the historical behavior of both premodern and modern bureaucratic elite-driven regimes, it again strains credulity to propose that these social formations are somehow less liable to corruption by an adherence to a overarching tradition or ideology—it is precisely in regimes that claimed that they were trying to pursue an overarching non-liberal common good that ended up having the greatest examples of ideological and political corruption, as cronies realized they could play lip service to the common good while arbitraging their role in their system for their own benefit. One only has to look at the privatization of the Soviet economy for a modern example of this in practice.

Deneen also considers the contemporary power elite to be filled with people using identity politics as a means to enforce their control over the underclass, but it’s quite odd to argue that the overarching political and economic elite class are somehow uniformly progressive; for a good example of the absurdity of this position, one can observe the rightward drift of Silicon Valley tech billionaire politics both socially and economically in the past couple of years. And yet Deneen would have us believe that somehow the underclass primarily faces its primary threat from the rise of the new “woke” managerial elite class (evolving James Burnham’s thoughts in The Managerial Revolution further for the 21st century); while Deneen may not share Sam Francis’s antipathy to Christianity or his white nationalism, it is quite evident that Deneen has returned to the idea of Francis’s Middle American Radical to serve as the modern foot soldier of aristopopulism. For Deneen, somehow the white small business owner dealing with social backlash makes them an example of the underclass being repressed by the socially progressive overclass, but to take this seriously would be utterly absurd. Do people think that a red-state small business dealing with decentralized backlash as a result of social views is somehow more oppressed than the LGBT community within the same state at the time? It strains credulity to argue that the latter is somehow part of a managerial power elite or that the former enterprise somehow represents “working class values” more than any LGBT consumer does, unless Deneen is defining any sort of minority as incapable of being “working class.”

Many other flaws appear in Deneen’s argument the moment it makes contact with reality. One of the egregious claims that he makes (and upon which much of the argumentation of Deneen’s class of right-wing pundits rely) is that the working class, or in Deneen’s more poetic verbiage, “the voiceless and the unrepresented” are likelier to vote for right-wing figures like Trump than their left-wing elite counterparts. This persistent myth has been shown to be untrue so many times over (for example, by YouGov and FiveThirtyEight) that one despairs of ever dispelling it and undertaking sober analysis of the Trump phenomenon. Inconvenient facts like the median Trump voter being richer than the median Clinton voter are put away for Deneen’s diatribe against liberal elitism. Another example of Deneen’s slippages is when he discusses “widespread populist resistance to pandemic mandates.” When the majority of Americans endorse the policies Deneen rails against, one wonders where the populism lies.

But really, Deneen shows no particular concern for facts. Deneen elsewhere claims that immigrants “undercut” the wages of native workers. The implication appears to be that the managerial elite’s cosmopolitan egalitarianism is actually rapacious market capitalism reliant on a cheap source of foreign labor. This point would be valid if there were any evidence for this fact. Anyone who has taken intermediate economics knows that Deneen’s basic theoretical assumption here presumes a lump-of-labor fallacy, but for simplicity we can point to the Panel on the Economic and Fiscal Consequences of Immigration’s extensive literature review of the empirical conclusions on immigration: an extremely modest negative effect on the wages and employment levels of low-skilled native workers. Furthermore, the immigration of high-skilled workers is found to have positive wage impacts for certain sectors of native workers. Regardless, the long-term effects of immigration in the literature are almost uniformly beneficial. But this kind of thing is not really surprising from Deneen, who appears to prefer discredited race scientist Charles Murray for his citations on “flyover country” deprivation to much more empirically solid literature on the same phenomenon such as the work of Autor, Dorn & Hanson.

Towards the end of the book, Deneen misunderstands Fukuyama’s formulation of the ‘end of history’—much like the left-wing he critiques in the book, he understands it as a form of democratic triumphalism. But Fukuyama’s work was not just the “End of History,” it was the “End of History and the Last Man.” For Fukuyama, the end of history was on one hand something to be expected as a result of modernization processes realizing that success required a specific political form, but this modern political form also came with new forms of legitimation crisis that would arise as a result of the inability for modern democratic regimes to provide recognition (merging Nietzsche, Hegel, and Kojeve’s thought into one political whole). Specifically, modern citizens desire both isothymia (the desire to be seen as equal) and megalothymia (the desire to be seen as superior). These desires, for Fukuyama, created the risk that we’d “slide back” into history and return to illiberal social arrangements. At the heart of the postliberal “regime change” project, and aristopopulism, do megalothymia and isothymia not play a role? For Deneen, the elites need Middle America, and Middle America requires the elites. If one were to put a Fukyamaist lens on this analysis, one would obviously notice that Deneen is trying to satisfy the need for megalothymia by reinventing the elite for a new, non-liberal era—one that would directly dominate again, and one that would uphold conservative values against “identity liberalism.”

Deneen’s inversions, obfuscations and tirades become exhausting after a while. One gets the impression that he’s equally as prone to the resentment-based politics as the shadowy liberal elite he rails against. Much of the book consists of nothing but diatribes against an ill-defined “laptop class” arrayed against an equally undefined demos that Deneen evidently belongs to. He rails against the reliance of liberalism on the Millian “harm principle,” but is given to bizarrely evocative descriptions of how middle American small businessmen are being trampled by coastal elites. He militates against the oppositional politics of “teams” while using the language of “Machiavellian means to Aristotelian ends.” Of course, in all this Deneen just so happens to be on the side of the demos against the managerial elite. But it beggars belief that a man who has degrees in English literature from Rutgers and political science at the University of Chicago, and has since taught at Princeton, Georgetown, and Notre Dame is somehow closer to the demos than to the managerial elite. Indeed, his work is characterized by an unexplained obsession with universities. When Deneen complains about how contemporary universities are engines of “gnostic” indoctrination, one is left wondering if Deneen’s actual problem is that they aren’t constructed so as to spread his own professional interests. Reading these sections, does anyone think that maybe the poor students mugged by propagandistic liberalism, utterly incapable of forming their own thoughts and opinions, need guidance from the doctrine of Professor Deneen, savior and prophet of America?

What is the “common good”?

Further credence to the idea that this is just a catalog of Deneen’s own personal bugbears is given by his incapacity to give a normative account of the “common good.” The idea, one supposes, is that the common good is what is conducive to “human flourishing,” but Deneen never argues for why this or that good is something that is conducive to human flourishing. Deneen might claim here that these goods are uncontroversially conducive to human flourishing, but if they were clearly uncontroversial then Deneen would not have written this book. But maybe this is tendentious of us; after all, Deneen might just be an impoverished sort of political realist here. That would still not explain his rank hypocrisy when he claims that a well-constructed government is one that restrains the passions, and true freedom is the freedom to be “well-governed.” Clearly Professor Deneen can, unlike the detested managerial elite, restrain the democratic excesses of the people. After all, the managerial elite are those who are against order, stability, and security, whereas Professor Deneen is for the common good (which just happens to be what Professor Deneen thinks is the good).

But there is something even more unsettling in the rhetorical patterns that Deneen employs. As is common with this genre of right-wing writing, antisemitic tropes proliferate throughout. When Deneen accuses modern liberalism of suppressing those who find themselves “rooted” somewhere, one cannot help but think of the charge of rootless cosmopolitanism. When he claims that the liberal political order has produced an elite that practices “placelessness, timelessness, and separation from cultural forms and practice,” is one not supposed to see the comparison to antisemitic screeds? These shadowy elites who can manipulate information and finance just so happen to be arrayed against the older school of aristocrats and productive industrialists. These elites also promote multiculturalism, diversity, what have you. Perhaps Deneen is unconscious of these undertones. However, and here we agree with Deneen, one must read works of literature within the traditions and communities they partake in.

Here we think there might be some benefit in saying something positive about Deneen’s work. If anything, his diagnosis of bureaucratic society seems on-point. A technocratic disconnect between the demands of a democratic population and of governmental apparatuses is well-illustrated by constant austerity programs, bans on abortion (but Deneen wouldn’t concede this one), lobbyist prevention of gun reform, or rigid zoning laws. Shutting down places of worship and schools during the pandemic might have had genuinely disastrous effects for the community and education that were not parsed by policymakers due to their narrow and oftentimes elitist approach to these questions, with no concerns for ordinary citizens. But as this collection of issues would indicate, there is nothing especially “liberal” about bureaucratization, and many of the ills associated with the constant interplay of special interest groups and policymakers are indeed straightforwardly conservative. Is there any greater example of bureaucratic capture in contemporary American political society than a few conservative lawyers well-entrenched in cushy think-tank jobs working to place an unelected caste of mandarins onto the highest court of the land to overturn democratic decision-making? Of course, it might be unfair to accuse Deneen of supporting “FedSoc.” After all, he wrote a critical NYT article with Chad Pecknold and Sohrab Ahmari on it. But once one sees Professor Deneen’s “contributions” page on the Federalist Society website, you begin questioning his actual commitment to his professed anti-movement conservative ideals.

What is left in Deneen’s project outside the perfectly anodyne and politically agnostic claim that there’s an increasing divergence between what bureaucratic apparatuses want and what the “demos” seeks? Nothing much at all, it seems. There has been much lamentation about the lack of thoughtful conservative political theory in contemporary academia. We are sympathetic to this perspective. If works such as Deneen’s are intended to remedy this gap, however, then perhaps it is better to keep conservatism out of the academy entirely.

Bibliography

Warner, J. M. (2018). The Friendless Republic: Freedom, Faction, and Friendship in Machiavelli’s Discourses. The Review of Politics, 81(1), 1–19.

Reinhardt, M. (1997). 2. Disturbing Democracy: Reading (in) the Gaps between Tocqueville's America and Ours. In The Art of Being Free: Taking Liberties with Tocquevile, Marx, and Arendt (pp. 20-58). Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press.

Takeda, C. (2019). Mme de Staël and political liberalism in France. Palgrave MacMillan

Vincent, K. S. (2011). Benjamin Constant and the birth of French liberalism. Palgrave Macmillan.

Dijn, de A. (2011). French political thought from Montesquieu to Tocqueville: Liberty in a levelled society? Cambridge University Press.

Chaloupek, G. (2011). Friedrich List on Local Autonomy in His Contributions to the Debate About the Constitution of Württemberg in 1816/1817. In Two Centuries of Local Autonomy (pp. 3–12). Springer New York.

Blau, F. D., & Hunt, J. (2019). The economic and fiscal consequences of immigration: highlights from the National Academies report. Business Economics (Cleveland, Ohio), 54(3), 173–176.

Autor, D., Dorn, D., & Hanson, G. (2013). The Geography of Trade and Technology Shocks in the United States.

Autor, D., Dorn, D., & Hanson, G. (2013a). Untangling Trade and Technology: Evidence from Local Labor Markets.

Autor, D., Dorn, D., & Hanson, G. (2017). When Work Disappears: Manufacturing Decline and the Falling Marriage-Market Value of Young Men.

Autor, D., Dorn, D., Katz, L., Patterson, C., & Van Reenen, J. (2017). Concentrating on the Fall of the Labor Share. https://doi.org/10.3386/w23108

Ahmari, S., Deneen, P., & Pecknold, C. (2022, June 14). We Know How America Got Such a Corporate-Friendly Court. New York Times. Retrieved from https://www.nytimes.com/2022/06/14/opinion/conservatism-federalist-society-populists.html.

Past events. The Federalist Society. (n.d.). https://fedsoc.org/past-events?speaker=patrick-deneen

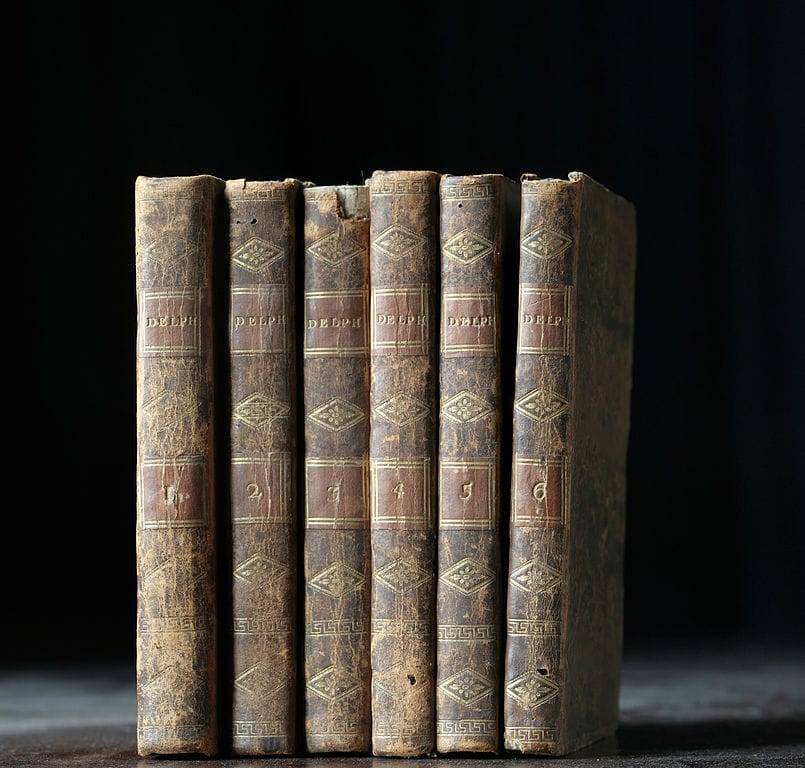

Featured image is Delphine, a novel by Madame de Staël, by Coyau