Now Is Not the Time for Moral Flexibility: The Example of John Quincy Adams

We must stand by the principles of the open society, pluralism, freedom, and mutual toleration.

Before he was inviting comparisons with Hitler and Mussolini, America’s 45th and now 47th president favored himself like another, decidedly more American demagogue. Andrew Jackson. In his first term, Donald Trump hung Jackson’s portrait in his Oval Office, praised Jackson’s populism, and declared his own victory over Hillary Clinton to be “greater than the election of Andrew Jackson.”

And so for this reason, among many others, I want to turn for inspiration ahead of the election to the man and former president forever linked to Jackson in the American historical imagination: John Quincy Adams.

John Quincy was both a man of immense intelligence and accomplishment and, in many ways, one of early America’s perennial losers. His solitary term as president saw much of his agenda stymied by the emergent partisanship of the Jacksonian era and his own inability to garner support for his expansive vision of internal improvements. Jackson, in many ways John Quincy’s opposite, would sweep to power in 1828. And the former president’s subsequent time in the House of Representatives would see him stand valiantly but futilely against the institution of slavery and the coming violent division of the Union.

He was, undoubtedly, his father’s son. Both Presidents Adams, as Nancy Isenberg and Andrew Burstein note, “voiced what few politicians ever speak aloud: a conviction that the people are not always right, can be misled, and will arrive at conclusions with insufficient information.” The authors add that “While humans remained subject to their passions, it was empirically that the favored theory of Western democracy did not ensure positive outcomes. The Adamses sensed this and did not shy away from saying so.”

John Quincy was morally fixed, but intellectually wide-ranging. He frequently spurned party loyalty and was fundamentally quarrelsome. As biographer Harlow Giles Unger describes the later Adams, “he was argumentative and politically unpredictable, but consistent in his fierce and constant defense of justice, human rights, and the individual liberties that his father and other Founding Fathers had fought for in the American Revolution.”

In his final years of public service, during which he served as a Representative from Massachusetts, John Quincy inveighed against the evils of slavery and bedeviled Southern attempts to stifle debate on the issue. Implacable in his contempt for the slave power and in his belief in the Union, he refused to be quelled by either procedural or physical attempts to constrain him. Historian Joanne B. Freeman notes that, in his years-long fight to assert the right of petition in the House, “What mattered most to him was forcing the issues, forcing the issue of slavery onto the floor, forcing the right of petition into play, and forcing slaveholders to display their brutality for all to see.”

If there are times when moral flexibility is needed, this is not one of them. In the age of Trump, too many have proven far too pliable. We’ve watched senators, media icons, and pastors hedge, demur, and dissemble when presented with the question of disavowing Trump. Their disgrace is only exceeded by those who have thrown themselves enthusiastically into his arms.

Partisanship is one factor, assuredly a critical one in the decisions of Republican elites who privately disdain Trump not to campaign publicly for his opponent. But the dramatic ways in which Trump’s victory has shifted some of the Democrats’ core constituencies beneath their very feet tells us it is not the whole story. Ultimately, it’s too early to cast about for electoral keys. But it is not too early to say the the reelection of Donald Trump is a moral disaster, a catastrophic decision for a people fortunate to enjoy the fruits of the freest and richest period in human history thus far. Those of us who stand against creeping authoritarianism and the rot in American civic culture will have to force the issue. We will have to be uncowed by the vitriol but also unswayed by the easy hatreds of partisanship and internet warfare.

Both John and John Quincy were students of the Roman statesman Marcus Tullius Cicero. And Cicero, too, offered words of caution about the corruption of republics and maintained a wry realism about the nature of public life. Take, for example, this note from famed classical historian Mary Beard: “'Cicero once said of Cato, ‘he talks as if he were in the Republic of Plato, when in fact he is in the crap of Romulus’.”

Popular government is inherently messy, vicious, and flawed because people, for as much good as there is in them, are also inherently messy, vicious, and flawed. It is not any less true for us now than for those of any other era, be it interwar Germany, antebellum America, or Cicero’s Rome.

The Democratic Party will undoubtedly debate how it should present itself going forward. That is what we expect of losing parties. There will be arguments about what policies it should or should not abandon and what rhetorical concessions to make. But I am not writing as a Democratic functionary, and in the spirit of the Adamses I want to reach above and beyond party interest to say plainly that I still believe in the open society, in the principles of pluralism, freedom, and mutual toleration. Even when they prove unpopular and unpersuasive, I believe in them still.

I fear I will be misread here as having disdain for the American voter or, worse, for holding democracy itself in contempt. But it’s precisely because I love and respect the American people and hold in such esteem the promise of a free government directed by public-minded individuals that I lament this occasion.

Here, I want to turn to a more modern political philosopher: that great American statesman, Daniel Patrick Moynihan. One of his best loved quotes comes from a lecture delivered at Harvard in 1986: “The central conservative truth is that it is culture, not politics, that determines the success of a society. The central liberal truth is that politics can change a culture and save it from itself.”

I believe the culture of liberal democracy, of the open society, of a vigorous and enlivened public can be re-established. And I think the method involves being attendant to place without abandoning universal principles. Such an approach requires us to be flexible in our thinking, open-minded in our understanding, and firm in our convictions. If we set about the work, I believe that the anomie of this age can give way to an era of even greater freedom, dignity, prosperity, and cooperation than we’ve known.

And yet the hard truth is that those are long and difficult fights, punctuated by frequent setbacks. Culture does not change easily. People often stand on principle only to be knocked down. John Quincy Adams lost the presidency to Andrew Jackson, who waged a personal war on the parts of government he disliked and visited horror on Native Americans. John Quincy did not win his fight against the slave power, and the Union did burst apart in the Civil War. History is not a story of linear progress. But it is one in which we all get to play our part, however small and, in a given period, however tragic. John Quincy’s historical efforts do appear tragic in many ways.

In addition to that, the parts played by John Adams and John Quincy Adams were of intransigent, difficult, prickly, and often uncompromising men—and crucially also revolutionary figures in American political life. But what sets them apart is the way, despite their imperfections, that they adhered to principle and solicited—more so, demanded—the same from those around them.

As Isenberg and Burstein put it “The Presidents Adams profited from history without fetishizing past knowledge, and they sought to protect history from those they considered frauds and propagandists.” So I hope to profit from the example set by John Quincy in particular by reiterating that the virtues of liberal democracy are worth defending with every bit of energy we have, even when it feels like a losing cause.

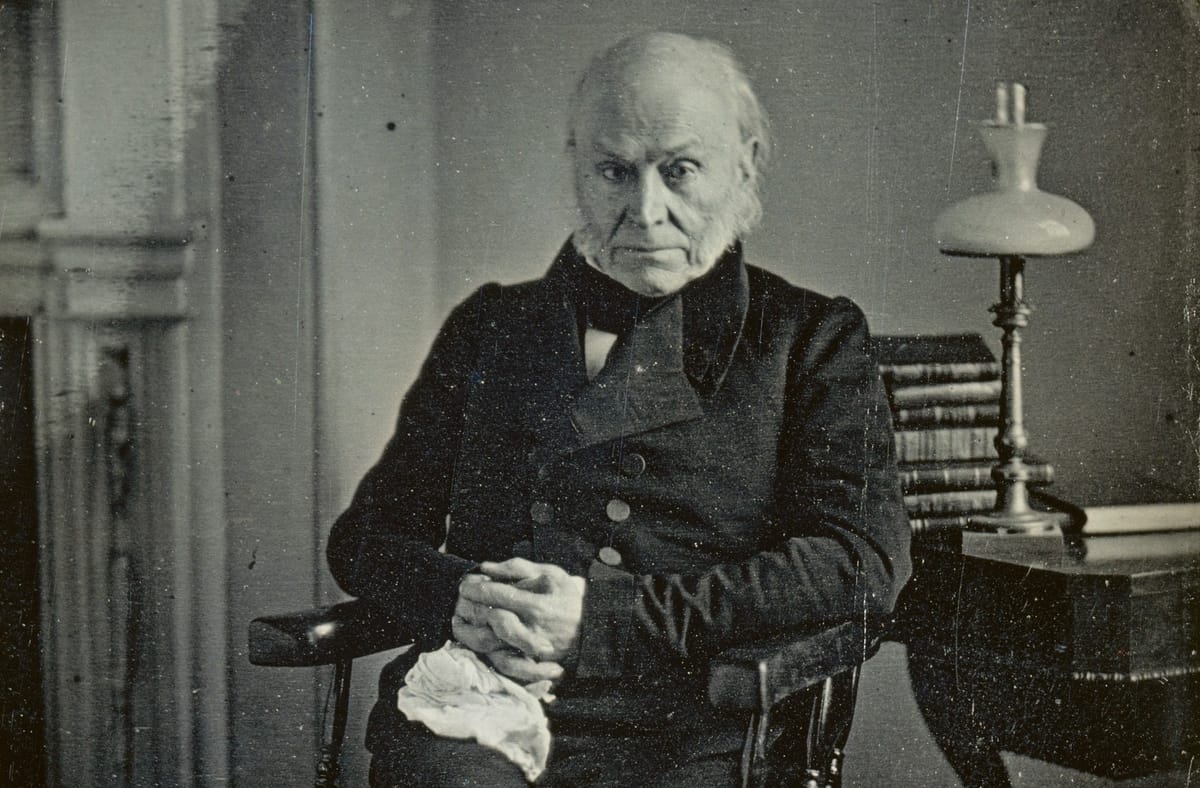

Featured image is John Quincy Adams