Kristi Noem Made a Lynching Postcard

The American tradition of celebrating racial terror.

Kristi Noem’s staged propaganda video in front of men in the El Salvador prison to which U.S. officials renditioned them has been drawing comparisons to the horrors of Nazi fascism. It’s easy to see why, and, frankly, I agree. The men behind her have had their heads shaved; they stand and sit on multi-decker bunks, looking toward the camera; and they are all there in the absence of due process.

But while I agree with the power of such comparisons both because they draw attention to the deeply fascistic nature of the second Trump administration and because there are very real echoes there, it is also important to stress similarities that exist in our own, American past.

Put simply: Kristi Noem made a 21st-century lynching postcard.

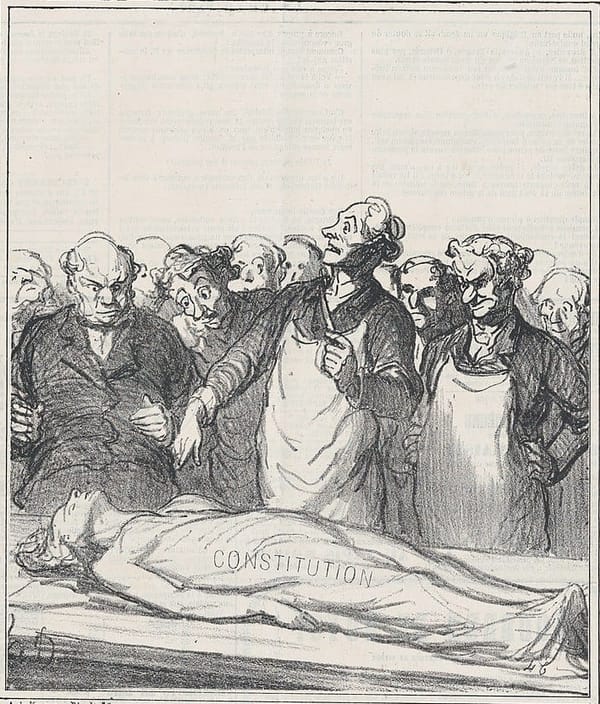

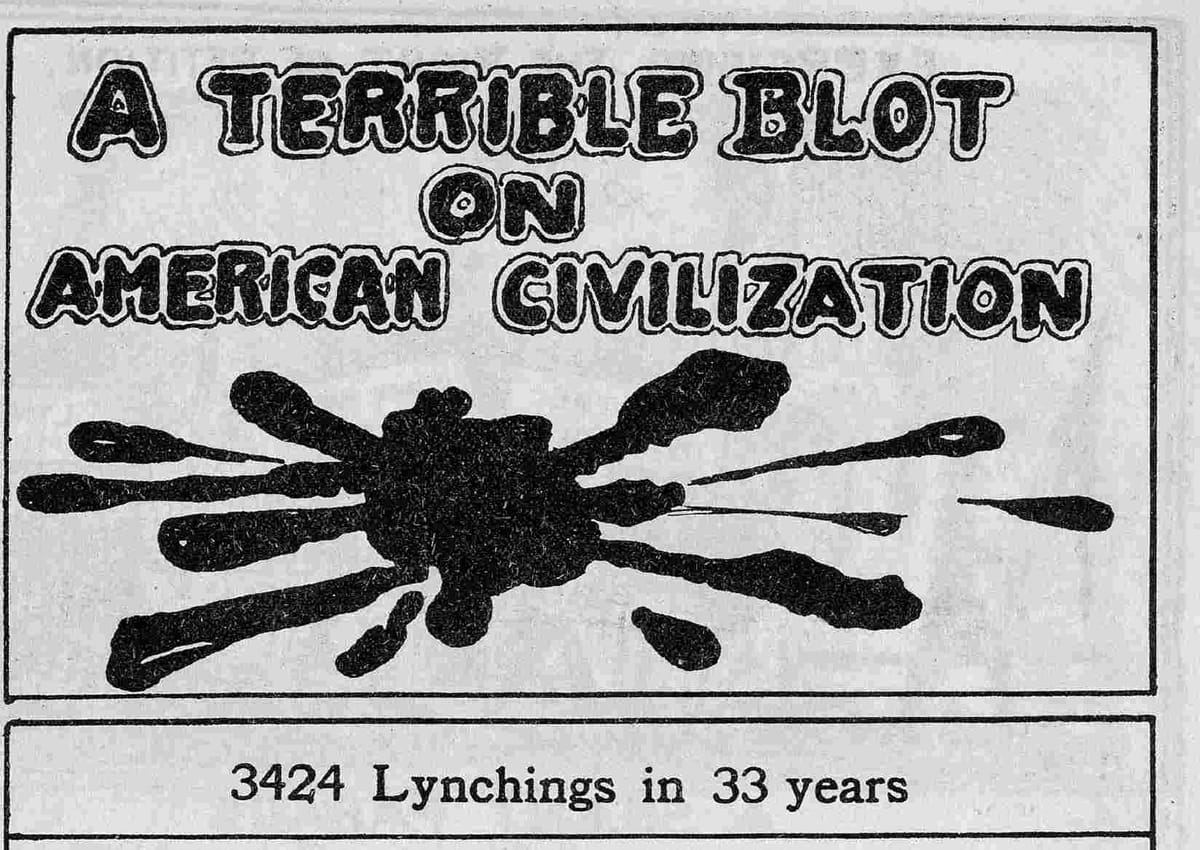

Lynching postcards are one of those pieces of American history that strip the bark off of anyone the first time they learn about it. Lynching itself—the ritualized practice of racial terror executions carried out against black Americans waged from the end of the Civil War until the mid-20th century—is a profound stain on our national history.

But many Americans are often surprised to learn that, as the decades of early amateur photography unfolded, whole communities would gather to pose and have their picture taken with the bodies of the victims. And these photos were frequently turned into postcards, purchased as keepsakes and also sent across the country as letters to loved ones and distant relations.

As historian Terry Anne Scott says in Christine Turner’s documentary short film Lynching Postcards; Token of a Great Day, “A postcard allows us to relive an experience. It also allows us to disseminate an experience. People use social media today to show other people what they are doing in their everyday life: ‘Look what I draw pleasure from.’ Lynching postcards were used in the same way.”

This capacity to spread the images produced at the scenes of racial terrorism were valued for their sentimental and celebratory values, as well as their usefulness as tools for communication and intimidation. Participants could claim the honor of a front-row seat, convey a sense of experience to the absent, and signal just what sort of violence their town was willing to mete out.

To quote historian Yohuru Williams from the documentary: “Lynching postcards [were] traded widely…One could be a celebrity if captured in a lynching photograph.”

Today, social media lets us send images everywhere instantly. And the Trump administration, MAGA, and the wider far right have seen the power of posting—text, yes, but especially image—content that evokes excitement among their allies at the same time as it produces disgust and fear in their opponents. All of this contributes to the virality of an image.

Just this past week, social media lit up with users using AI to “Ghiblify” pictures, rendering all sorts of photos in the warm, friendly shapes associated with anime films like “My Neighbor Totoro” and “Kiki’s Delivery Service.” MAGA also got in on the action, posting a Ghiblified photo of a woman in tears being cuffed by an ICE agent.

Lynching postcards were so popular and widely spread that the U.S. government banned sending them through the mail via an amendment to the Comstock Act in 1908. But as scholars like Linda Kim have noted, this did not actually stop the spread and even mailing of lynching postcards. Moreover, no national anti-lynching law existed, and it wouldn’t until 2022.

Many participants in these lynchings turned out in fine attire and even smiled for the camera. Noem posed in front of the cell with her hair curled, a diamond ring on her finger, and a watch reportedly worth up to $65,000.00 on her wrist. In her video, Noem is playing the part of an influencer as much as a government official. It feels like something with all the trappings of Instagram sponsored content, but it is a message of state propaganda with a backdrop of fascistic violence and injustice.

I’ll make the comparison to postcards again. The reason people in these lynching images could become famous is precisely because their faces were unobscured. As Williams notes, “The reason those people are unmasked is that there’s no fear they’ll be prosecuted for their actions… It is terrorism in its clearest expression. And in some of the most infamous lynchings…it’s also an example of the complicity of state and local government.”

Due process does not exist for the people locked in the El Salvador prison. But there is also no fear that Kristi Noem will be investigated for a media stunt in which she flew to another country to stand in front of El Salvadoran inmates, despite the fact that we know very little about the identities of the Venezuelans deported to this prison by DHS. It’s a sleight of hand meant to imply no difference between gang members arrested in El Salvador and the people we renditioned to this hellscape without anything resembling justice. And it still entails the abuse of prisoners, who were carefully posed for a PR video by an American official gleefully violating the Geneva Conventions.

I really don’t want to be glib about this comparison. Lynching has a long, wretched history in the United States. And its central role has been about the control, abuse, and degradation of black bodies and thus black life. But lynching was also used to terrorize people of Mexican heritage, as well as Asian-Americans and Native Americans, in the American southwest and west. Some of these, too, were photographed.

The echoes of dehumanization, terrorism, fetishization of bodies, celebratory violence, and virality are clear. And they are important because they are American echoes.

It’s not a local sheriff or mayor or even a governor. This is the United States government, at the highest levels, reveling in its abuse of immigrants, flexing its willingness to dispense humiliation and apply violence, and sending a clear message it will defy our country’s laws and judges when it pleases. Kristi Noem is there, wrist glittering and hair curled, to show us their dehumanized bodies and remind us that protections do not exist for the type of people this administration deems undesirable.

As both Jonathan V. Last and others at The Bulwark have stressed repeatedly, we know that there will be no investigation of Noem or anyone else in this administration. There will be no accountability—at least, not if they can help it. But the video, with Noem front-and-center, is already everywhere. For people like me, it’s a source of rage and despair—a viscerally upsetting image of deeply cruel behavior. But for others, it is a source of delight.

When Kristi Noem says “we will hunt you down,” there’s no question that she also means, if I can put some words in her mouth, “and arrest you, deny you of due process, and ship you to another country for you to be abused and humiliated. We won’t even bother to check if we have the right people because that’s not what this is really about. It’s about subjugating and terrorizing people we don’t like on behalf of those we do. And we will do it all because we can, because we take pleasure in it, and because it delights those who are with us.”

That’s what lynching postcards were for. And that’s what Kristi Noem produced.

Featured image is A terrible blot on American civilization, by District of Columbia anti-lynching committee