It's Not the One Percent. It's Your Neighbors.

The rentier economy that has a stranglehold on American quality of life includes a lot more than one percent of the population.

A spectre is haunting America: the spectre of Bad Vibes. People don't like how the economy is working, or at least they say they don't. We live in an era of unprecedented material prosperity, but this is accompanied by deep-seated popular discontent with the overall shape of the economy. Arguably the first great irruption of this discontent was 2011's Occupy Wall Street. This anger at big banks, big corporations, big billionaires, the inherent unfairness of the current economic situation would prove to be far more durable than brief-lived Occupy proper. Bernie Sanders' 2016 and 2020 presidential bids continued to channel this discontent—and, some argue, so do Trump and Trumpism.

So what's wrong, and how do we fix it? How do we restructure the American economy to work for Americans? Occupy provided one enduring answer. Occupy was a chaotic and leaderless movement, but their slogan was clear enough: "We are the 99%." The slogan provides an evocative diagnosis of what ails America. We are a land of tremendous material productivity and prosperity, but that wealth is being hoarded by a tiny minority. The one percent use their wealth and power to warp government and the economy in their favor, channeling our hard-earned wealth into their already obscene profits. The problem is inequality, and the answer is redistribution: punish the bad guys, reappropriate their hoarded wealth, and redistribute it to the exploited masses.

Why is housing so expensive? Corporations are buying up all the houses and keeping them empty and pocketing the profits while ordinary Americans go homeless. Why is the Earth warming? Just one hundred corporations are pumping out 71% of all global carbon emissions while ordinary Americans are stuck living with the hurricanes and wildfires and droughts. Why is our public transit falling apart? Greedy corporations have starved our cities of money and given themselves a tax cut.

The 99v1 story is compelling. But it is not the only picture of what ails us on offer in the contemporary political scene. According to this other picture, our problem is not inequality per se: it's rents. A rent, in the economists' peculiar language, is income earned not from real production but from mere scarcity. A given person's income might be quite extraordinary, but not unearned. Taylor Swift's ongoing Eras Tour has already grossed more than one billion dollars, but that money has been generated by delivering a product that is, clearly enough, highly desirable, and in an overall marketplace (music generally, live music specifically) that is relatively competitive.

By contrast, after the first oil shock in 1973-1974, the Organization of Petroleum Exporting Countries (OPEC) discovered that they had substantial cartel power over worldwide oil prices. In the coming decades, they would repeatedly restrict the total supply of oil in order to drive up its price. And since there's only so much oil in the ground in only so many specific places, there wasn't much anyone could do to compete with them by entering the market and undercutting them. A substantial fraction of their profits were rents: over and above the use-value of the oil they produced, there was the value they could extract from the world simply by having no competitors.

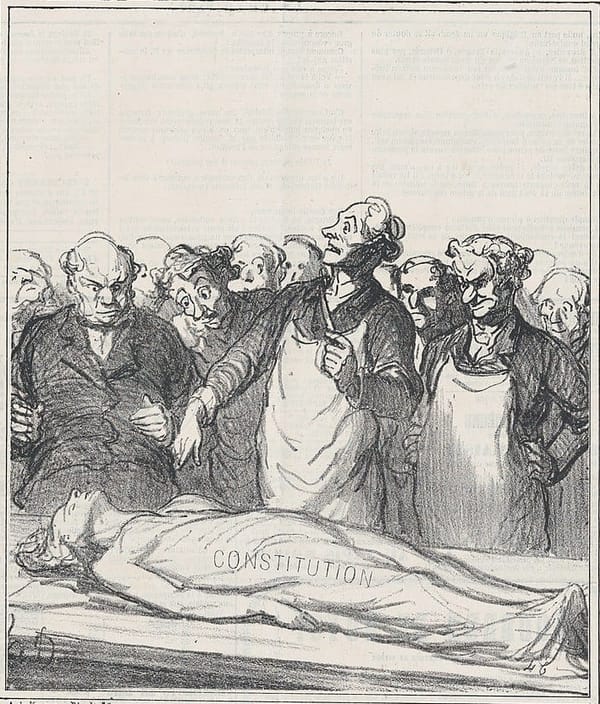

The exact econometric definition of rents and how to measure them, especially when a given income stream partly involves real production and partly involves mere scarcity, is a technical question that need not concern us here. Under all these definitions, a central feature of rents is that scarcity allows for extraction. Sometimes this scarcity is "natural" scarcity, as in the case of OPEC above—relative scarcity of some finite natural resource. In other cases, the scarcity is artificial, as in the case of the guild monopolies that pervaded ancien regime France—or the protectionist regulations responsible for the baby formula crisis that gripped America in 2022.

Artificial scarcity occurs when the power of law and the state is used to deliberately restrict the supply of some good or service. Although these laws are often brought about by pressure from the rentiers who profit from them, this is not always the case: artificial supply restrictions can be brought about by other means, such as the aesthetic concern with maintaining the image of the belle epoque that dominates Parisian planning.

According to this alternative picture, the idea of the rentier economy, the core economic problem of our times isn't inequality per se: it's artificial scarcity. Pouring more money into a sector that is already dominated by rentiers won't get more goods to more people. All that money will just wind up in the pockets of the rentiers without increasing supply, because the supply is artificially restricted—that's the whole point. Spending more money on oil wouldn't buy you more oil if OPEC decided there wasn't going to be more oil—it just put more money into the pockets of Gulf monarchs. (I simplify: spending more money would get you more oil; it just also meant that someone else got less.) What was needed was more sources of energy.

So there are two pictures of what ails us. One is associated with a resurgent progressive movement, one with the "abundance agenda" of the "neoliberals." Which is more accurate? Let's consider a specific policy area—and since this is a Samantha Hancox-Li essay, you already know that area is "housing." The 99v1 picture tells us that we already have enough housing. But it is being hoarded by a small group of villains—corporations, developers, the ultrarich. First step: punish the bad guys, reappropriate their hoarded wealth. Some options:

A vacancy tax, to soak the rich and their empty vacation homes and investment properties. A ban on corporations owning single-family homes, or perhaps a general ban on anyone owning more than a few units of housing. A tax on luxury construction, to provide for permanently affordable housing. Second step: use the "windfalls" from these moves to provide money to the downtrodden many to purchase that which they have been denied: a subsidy for first-time homebuyers, or a subsidy for first-time homebuyers, or perhaps a subsidy for first-time homebuyers.

We don't particularly need to tell just-so stories about how these programs work in theory. They've been tried in various places, and we can simply look at the evidence. In 2023, the California Dream program provided $300 million in downpayment assistance to first-time homebuyers. That fund was depleted in 11 days by 2,564 recipients, disproportionately recipients in the Sacramento area (that is to say, those who were connected to legislative staff and therefore knew the program was coming). But one can hardly blame them: after all, they immediately turned around and handed all that money over to someone else—people who already owned housing in a state famous for lacking it. It did not spur some construction boom in California. It just changed which people won this particular round of musical chairs. California is estimated to have a housing shortage of between three and four million units. A cash transfer of even $300 million, even if it had translated perfectly into new construction, is a drop in the bucket of what's needed. In practice all it's done is inject $300 million into an already overheated housing market—to the benefit of existing homeowners and their lucrative land rents, of course.

According to the rentier economy analysis, the problem with housing is not that there are vast tracts of empty apartments being hoarded by the ultrarich. The problem is that the supply of housing has been artificially restricted—by zoning codes, by deliberately sabotaged fire codes, by malfunctioning environmental laws—to the point where we simply do not build enough housing in the most desirable areas. This has the simple effect of magnifying the rents of ownership. An empty lot in my neighborhood sold for $13,500 in 1996 (about $26,800 in today's dollars). Today that lot is listed for $155,000. It is just an empty lot—no improvements whatsoever have been made to it, much less $128,200 worth. That radical increase in equity is a rent: the price of mere scarcity, the price of the strangulation of housing in my neighborhood by decades of anti-development lawmaking.

The housing example reveals something core to the rentier economy: the beneficiaries of artificial scarcity are not always some tiny distant minority. It's not megacorporations and the megarich but your friends and neighbors, your parents and relatives, the 65% of Americans who own their own home and expect the equity value of that real estate to increase, forever, guaranteed, faster than inflation or wages.

I don't want to discount the dangers of concentrated wealth; I don't want to discount the threat of plutocratic control. But a fixation on populist grievance can lead policy down some bad blind alleys, and turn policy away from actually doing something about our worst crises. As longtime activist and Occupy leader Jonathan Smucker admits, the power of the 99v1 slogan was that different groups could project different meanings onto it. We see this clearly enough today, as right-wing reactionaries rail against (((elites))) "stealing our country." The most important function of the 99v1 slogan is to "focus attention on the real villains"—which is to say, absolve you. It's not your car that's producing carbon—it's corporations. It's not your NIMBYism that's driving up the price of housing—it's corporations. The real villain is far away and very different from you. Fixing things won't require you to accept any changes in your world, just to take some stuff from those villains far away. We can fix everything, for free.

Here's the real secret: we don't live in the world of the ancien regime, where 90% of the population had net zero wealth. We live in a middle class society, with a median household income of $74,580 and assets of $166,900. And the thing about rents is that they flow to a lot more than one percent of the population. It's not just the megarich, the billionaires with yachts for their yachts. It's "don't call me a millionaire" millionaire homeowners, it's doctors, it's car dealers, it's cosmetologists. In America we have built ourselves our very own License Raj, and a great many Americans think they benefit from their own little slice of it—even as everyone else's little slices are cutting them to pieces.

The rentier economy analysis shows us why the 99v1 programs are not merely failures, but exacerbate the problems. Mostly what happens is they funnel all that money into rentiers' pockets and change nothing. Indeed, the fact that these demand-subsidy schemes tend to be so carefully targeted at specific products—"here's a pile of cash but only for buying housing"—itself suggests that they are intended to benefit rentiers. But this is an ill-considered populism that only exacerbates the underlying problems and leads voters to seek more radical solutions.

The rentier economy is the concept that will allow us to fix our ailing economy without snake-oil populism. Breaking down the rentier economy means breaking down all these little protectionisms—while credibly promising that we can each give up our little fief and still be safe and secure and prosperous. This means aggressive, broad-based welfare programs, like the child tax credit, like universal health care, like social housing. This means a future in which every American's baseline material security is guaranteed not through rents extracted from a stagnant economy but public services built on the basis of a free, flourishing, fast-growing economy.

Featured image is Sylvan Terrace Rowhouses, by CaptJayRuffins