Is It a Coup?

It is bad, it is illegal, and it is a self-coup.

I study coups. I fielded the “is it a coup?” question in 2021 and have been fielding it now as well. I think it’s worth specifying how political science answers the question and what the implications are of a “yes” or a “no” answer. What we are seeing from the Trump administration is usually called a “self-coup” or autogolpe, which has a specific set of risks and possible responses within the state apparatus. Sometimes “is it a coup?” gets used as a stand-in for “is it bad and/or illegal?” I want to be clear that it is definitely bad and definitely illegal. What we want to know beyond that is what is happening, how does it succeed, and what can we do?

What is a coup?

A coup is an attack on the state (literally, in the French coup d’état). The state is a political organization with a “a claim to the monopoly of the legitimate use of physical force.” In this definition I want to highlight “legitimate” and “use of physical force.” These are equally important, but opposing, aspects of the state. For a state to be legitimate, people must believe it has the right to do what it does. In medieval monarchies, this belief was in the divine right of the king to rule over his subjects.* Today, it is usually the belief that the decisions of the state have their origins in the will of the people.

At the same time, the state uses force to back up its authority. Its existence is threatened if anyone fails to respect its legitimacy, so those who break laws are forcibly detained, made to pay fines, and even killed. This use of force is “legitimate” in that people generally agree the state has the right to do these things, and you would not, for example, expect a police officer to be accused of kidnapping after making an arrest.

When I say a coup is an attack on the state, I can go further to say that a coup is the use of force to take control of the state. It is the illegal removal of a leader by force or threat of force by those within the government. There are lots of ways to slice this definition, but the main ingredients are 1) removing a leader, 2) force, and 3) within the government (the last differentiates a coup from an armed rebellion). Compare to Powell and Thyne’s definition: “illegal and overt attempts by the military or other elites within the state apparatus to unseat the sitting executive.”

A coup, especially against a democratic government, is a blow to state legitimacy. For a state to have legitimacy, there needs to be some feeling among the people that their government is the “right” government. National militaries are often popular, so a coup can have some level of legitimacy ascribed after the fact (especially if the previous government had very little legitimacy, which is why coups against British client monarchies in 1952 in Egypt and in 1958 in Iraq were celebrated as “revolutions”). But who prevails in a coup has much more to do with who can bring the most force to bear than it does with who has the most legitimate claim to power.

This might not necessarily sound like what is going on in the United States right now. What is happening has a lot more in common with a “self-coup,” often referred to with the Spanish term autogolpe. A self-coup is when someone who is already the executive tries to dramatically increase their power at the expense of other government actors, also illegally. This distinction is not made just to be pedantic. The two acts have very different implications for the state and power.

A self-coup, especially one involving a democratically elected executive (President or Prime Minister), is a subtler attack on legitimacy. We generally agree that, for a democracy to work, it needs to have more than an elected dictator—there have to be meaningful restraints on the powers of even elected governments. A “democracy” with regular elections, but where only media sympathetic to the prime minister are allowed to operate, does not have fair elections.

Only if an executive chooses to challenge or ignore restraints on their power is this a step toward the elected dictator model. Presidential systems like ours are particularly vulnerable to this because the executive is in office for a set amount of time, and it can be exceedingly difficult to remove them before that time is up. If they violate the law, who will stop them? Each country has a different answer for who is “supposed” to stop them, but generally a constellation of other government actors (the legislature, courts, civil service, and, yes, law enforcement and military) should stand in the way. There are several ways that a confrontation between the executive and other parts of the government can be solved “legitimately,” within the laws of the country. Only if the executive keeps challenging, and keeps going beyond the law do we get into attempted self-coup territory. And here we still find that force is the last word in control of the state. When all options are exhausted, does the military obey the law or obey the president?

We can see this dynamic playing out in the self-coup of Tunisian president Kais Saied. In 2021, Saied invoked an emergency clause of the constitution and used it to close Parliament, fire the Prime Minister, and arrest his opponents. The military obeyed his orders to close the parliament, refusing to let parliamentarians into the building. This was the path of least resistance for the military, as in normal situations they should obey the orders of their superiors, all the way up to the President. But in this case, it was an illegal order, and the accession of the military cemented Saied’s self-coup. The illegitimate action could only come to fruition through its recognition by the users of force in the government.

The other problem with a self-coup is it is more difficult to inoculate a government against the possibility of an executive overreaching their authority. Milan Svolik has found that democracies “consolidate” against coups from the military after twenty years without one. After that period, they are much less likely to undergo a coup. There is no such drop-off for the risk of a self-coup (for Svolik, “incumbent takeover”).

So, what’s happening in the US?

To make a very, very long story short: People working for Elon Musk, who is technically working for President Donald Trump, have attempted to suspend large parts of the federal government, including a total closure of the U.S. Agency of International Development (USAID). They have also established a back door into the Treasury system that distributes funds and have possibly already used it to stop funds. They are trying to end the 14th amendment. They are firing people en masse from the civil service, including those they consider their political enemies, those who they suspect of promoting “diversity”, and anyone else, for any reason. They do not have the legal authority to do any of these things, and in many cases not even the security clearance to look at the things they are shutting down. There’s obviously more, but these are probably the most “coup-like” actions being taken.

This is clearly in the realm of self-coup rather than a coup displacing an executive. Musk seems relatively autonomous, but even his illegal power derives directly from Trump. Nothing Musk has done can prevent Trump from locking him out of all government buildings tomorrow. So, this is the illegal action, and if left standing it basically gives Trump an unoverridable veto over all legislation, including civil service protections, past and future. That is illegal and unconstitutional, so we have illegal and increasing power at the expense of others checked off.

What will anyone do about it?

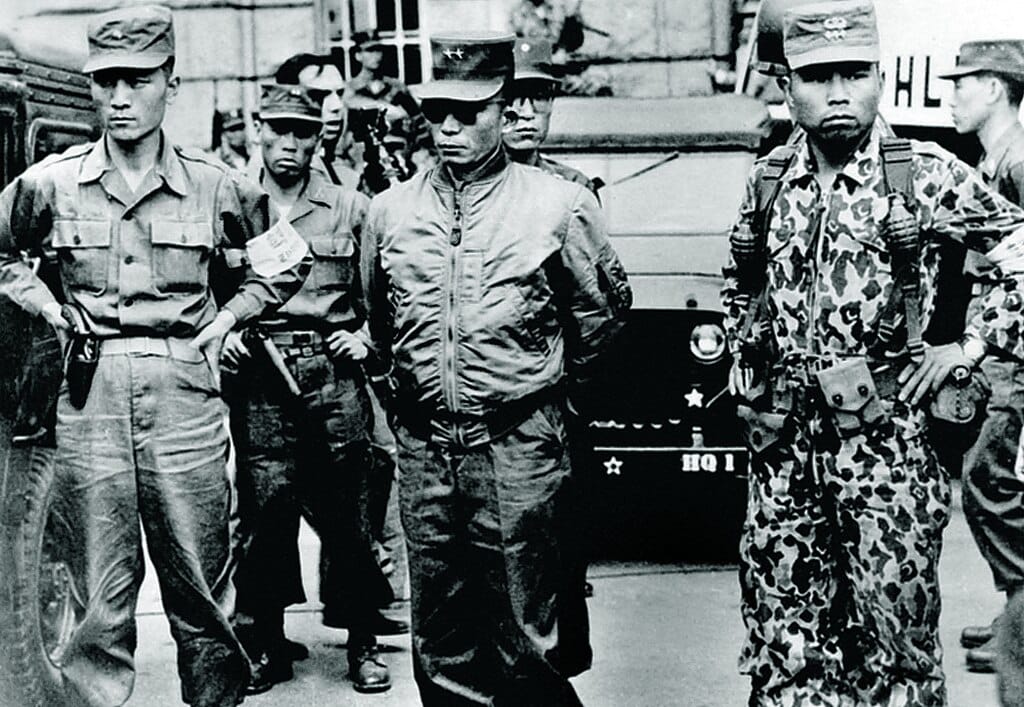

Even in a presidential system, we have built-in bodies to check the power of the executive. Unfortunately, Republicans control both houses of Congress, and the Republican party of Trump is not like the Republican party of Nixon: if there is a limit to the illegality they are willing to put up with from Trump, we have not yet seen it. Democrats in the Senate can make a stink and slow things down, but without Republican defectors they are limited to that. This is a big problem. Legislators tend to be the elected officials with the closest connections to their constituents and, therefore, the most legitimacy. It was quick action by the legislature, including members of the President’s own party, that beat back the self-coup attempt by South Korean president Yoon Suk Yeol.

That leaves us with the courts, the civil service, and law enforcement. Here the story is more optimistic. Courts have paused some of these orders and are escalating when they feel they are being ignored. Civil servants are bringing more suits, using the laws intended to protect them from exactly this kind of political purge. The FBI has indicated that it will not roll over and be purged.

But, one million online commenters cry out, what if Trump (or Musk) ignores all of that and does what he wants? That’s when we move from the realm of legitimate power to use of force. Specifically, though, that is where we must ask: where does legitimacy lie according to the people who use force? If a judge orders an action to cease and the executive refuses, who gets to call the police? Who do the police listen to? If people don’t leave their positions, who makes them? I think that at least Musk thinks that computer infrastructure is the new use of force, and what he’s doing in the code will put him in charge. But as XKCD illustrated, there is no substitute. Who the guys with guns listen to is always the last line in state politics.

That doesn’t mean it’s a good thing if the FBI or even the military has to step in here! I study the coup trap, the finding that coups tend to lead to more coups. One thing that drives the coup trap is that, once there is a crisis, you can’t quite make people forget that the military plays this role—especially the people in the military who played the role. I think, though, about something Jamelle Bouie said about prosecuting Trump during the Biden administration: “So now we’re in a place where we have lots of bad options. And I think the least bad option is a prosecution, because at least that communicates the essential message that presidents are not above the law, that the law applies to president as well, even when they’re out of office.” We are facing even worse options now (partially because Merrick Garland did not follow Bouie’s advice). We must try to aim for the best of them.

To that end, I’m going to list the potential resolutions from best to worst:

- Courts rule that everything is illegal. Trump backs down, blames Musk, fires him. This has the least damage to the legitimacy of the law, as it preserves the power of the courts to say whether the executive is enforcing the law.

- Courts rule that everything is illegal. Trump refuses to back down, civilian law enforcement intervenes against him. This could play out in any number of ways, but would likely involve federal law enforcement following court orders to halt illegal activity. This would likely be messy, as the administration might continue to fight to get their own people into law enforcement bodies to end any resistance. Depoliticizing the Departments of Justice and Homeland Security afterward would be extremely difficult.

- Courts rule that everything is illegal. Trump refuses to back down, military intervenes against him. This would end the U.S. military’s long history of neutrality in politics (with a couple notable exceptions), and so even in defeating the self-coup could leave us more vulnerable to future military interventions in civilian politics.

- Courts rule that everything is legal. Peaceful self-coup succeeds. This would drastically strengthen the President compared to all other actors in the government. It is impossible to predict all the possible effects of this, but at the very least elections for president would now mean an all-or-nothing battle to control the federal government. This would incentivize political violence and election fraud.

- Courts rule that everything is illegal. Military and/or civilian law enforcement intervene on Trump’s behalf. Violent self-coup succeeds. This is essentially what happened in the Tunisian case above. What makes this worse than the peaceful success is that the military in this case is also politicized on behalf of the government in power. This makes free elections in the future even less likely.

- Courts rule that everything is illegal. Military and/or civilian law enforcement divide and fight themselves. Civil war breaks out. This is the least likely, but by far worst possible outcome. We see in Sudan the devastation that can be caused by a coup turning into a civil war. It is unlikely because, absent prior politicization, military officers tend to prioritize unity over any political goal.

There are obviously middle points in between some of these. Courts work slowly but can be creative in how they make sure their rulings are enforced, and of course some arrogations of power might be ruled legal and others illegal, but I feel like this gives an idea of what we’re looking at.

In the meantime, popular pressure—visibility in the streets, calling legislators, talking to media, and even (sigh) posting—tells the actors involved what side the people are on. We are the ultimate source of legitimacy. Those in a position to stop this may or may not feel some abstract obligation to “the law.” You want to remind them of their obligation to the people. Express your opposition, however you can.

Verdict: Self coup, in-progress, success still unknown

*This is a simplification. Please forgive me, medievalists!

Featured image is from the May 16 Coup in South Korea