Inherent Vice: Can America Come Back From Who We’ve Become?

At the richest moment in world history, in an unparalleled time of comforts and luxuries, we have elected self-harm and self-pity.

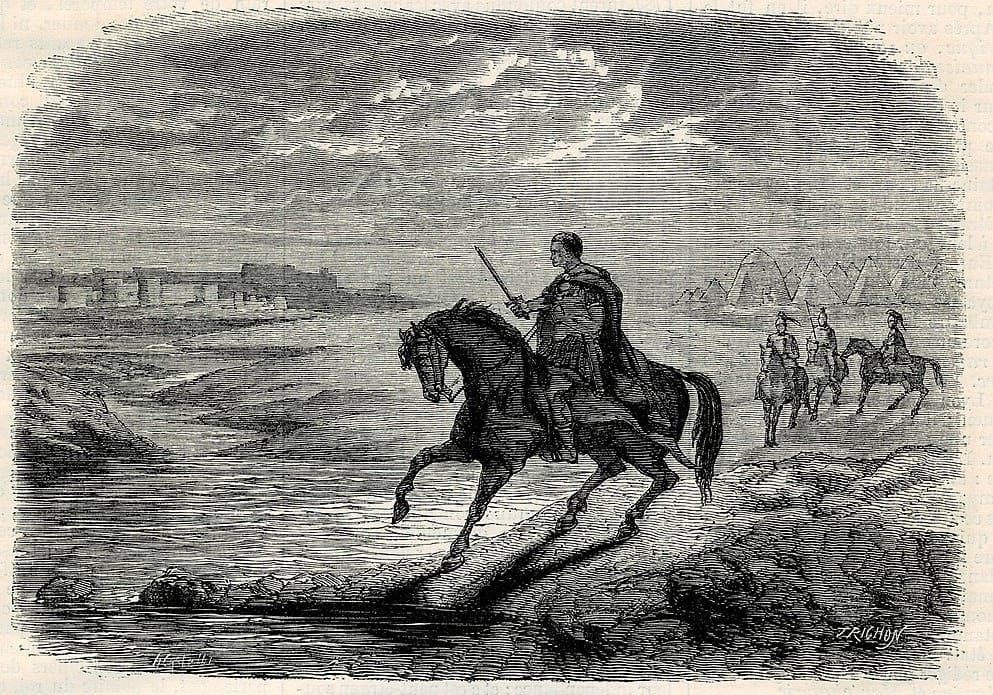

Scipio, when he looked upon [Carthage] as it was utterly perishing and in the last throes of its complete destruction, is said to have shed tears and wept openly for his enemies. After being wrapped in thought for long, and realizing that all cities, nations, and authorities must, like men, meet their doom; that this happened to Ilium, once a prosperous city, to the empires of Assyria, Media, and Persia, the greatest of their time, and to Macedonia itself, the brilliance of which was so recent, either deliberately or the verses escaping him, he said:

‘A day will come when sacred Troy shall perish, And Priam and his people shall be slain.’

And when Polybius speaking with freedom to him, for he was his teacher, asked him what he meant by the words, they say that without any attempt at concealment he named his own country, for which he feared when he reflected on the fate of all things human. Polybius actually heard him and recalls it in his history.

This extended quotation comes from the Greek historian Appian’s account of the Punic Wars, written in the 2nd century A.D. and depicts the Roman general Scipio Aemilianus’s reflections after conquering and destroying Carthage, Rome’s greatest adversary.

Rome’s empire would not collapse until the 5th century A.D., but the death of the republic was much nearer than Scipio Aemilianus might have thought and was thoroughly in the rear-view mirror when Appian wrote his history.

I’ve thought about this scene lately. I have been wondering if past generations should have wept watching the ecstatic celebrations as the Berlin Wall fell, knowing now how Americans would, with similar fervor, smash the windows of the nation’s Capitol and turn its hallowed halls into a latrine of despotic energies. Should we have wept as we tore down Nazi banners from European buildings or as we greeted American sailors and marines home from the far-flung Pacific, knowing now that an American president would threaten to invade our neighbors and deploy masked police to send migrants to rot in an El Salvadoran concentration camp?

Before Alaric and Odoaecer sacked Rome, it first descended from the ancient world’s most formidable republic into an increasingly tyrannical empire—even if it would reach its geographic, military, and financial heights as an imperial and not a republican state.

Caesar’s rise to tyrannical power was not the glorious ascent of some noble warrior to ultimate power, but a grasping, corrupt climb by a vicious opportunist, achieved through gangsterism, conspiracy, and intimidation. Caesar first secured a lock on power by allying with the vainglorious general Pompey and the unscrupulous business magnate Crassus. As co-consul, Caesar effectively neutered his fellow co-consul’s capacity to oppose him with threats of violence and mob appeal. Eventually, he would seize even greater power, leveraging bloody campaigns in Gaul and a populist instinct at home to position himself as dictator for life.

What Caesar and the figures like him down through the centuries represent is the undoing of republican norms by men whose wants know no end. Even as such men promise to break through the inefficiencies of representative government, their quest for power obliterates the system they claim to be saving.

We no longer have to ask if Trump is a Caesarian figure. His aspirations are clear. His malice for representative government and disdain for laws and customs are beyond question. He is other things, too—a brute, a fascist, a maniac.

But we put him here. And we did so this past November after he’d already shown us his fangs.

So there is no mystery to Trump this second time. His third campaign was his most brazenly fascistic of all. People will turn to all manner of saviors in times of crisis, but America, despite the pinch of inflation and troubles controlling illegal immigration, was not in a crisis. No, instead we turned to Donald Trump to fix much smaller problems, while choosing to overlook the 34 felony convictions he had accumulated since leaving office and the bloody self-coup he attempted only four years before.

As historian Edward J. Watts argues:

Above all else, the Roman Republic teaches the citizens of its modern descendants the incredible dangers that come along with condoning political obstruction and courting political violence. Roman history could not more clearly show that when citizens look away as their leaders engage in these corrosive behaviors, their republic is in mortal danger.

We have become all too willing to look away today. We accept dishonesty and rapaciousness in public life. We look away from uncomfortable facts and divert our attention with glowing screens and easy entertainment. We walk daily through a miasma of vitriol, ignorance, and petty politics. And, when a man who has shown us time and again who he is promised to make our lives a little easier, we put him back in power.

Not Good Enough

Donald Trump’s approval ratings have finally taken a dip. While the 45th and now 47th president has never enjoyed the honeymoon highs of his predecessors, he had been maintaining a relatively strong position for someone who spent a substantial part of his first term with an approval rating in the negative double-digits. That has started to crumble a bit now, but I find it hard to be sanguine about the situation. After all, a sizable minority of Americans are willing to support Trump. And just under 50 percent of voters opted to put him back into office only a few months ago.

According to former FiveThirtyEight guru G. Elliott Morris’s polling aggregate, Trump’s approval has gotten steadily worse, sitting at -8 as of the latest update. In other words, his position is quite weak but not disastrous. What I am l troubled by is the fact that, while disapproval is rising, a sizeable amount of Americans are still ok with what’s happening or even supportive of it. Take these recent figures form the New York Times/Siena poll: 66 percent of Americans see the Trump administration’s handling of things so far to be “chaotic,” 59 percent “scary,” and 42 percent “exciting.” It’s that last number I want to linger on.

Exciting? The Trump administration has so far pursued an immigration regime of pure horror—plainclothes ICE agents are picking up international students off the streets for their speech, detainees are being disappeared in defiance of judicial orders, and alleged gang members are being sent to a concentration camp in El Salvador without due process or any substantive evidence being publicly produced.

The administration barred the AP from the press pool in an effort to bend it to compliance, and they have used an anti-DEI campaign to attempt a takeover of some of the country’s most illustrious universities. The president has threatened to annex Canada and Greenland. Elsewhere, Trump has spit on the very idea of constitutional constraints and speculated repeatedly about seeking a third term.

Through all of this, and even as disapproval has risen, Trump still spent nearly all of his second first 100 days with his net approval slightly better than it was at the outset of his first term. And on individual issue questions, the disapproval ranges from resounding to tepid.

Per G. Elliott Morris, Americans massively oppose deporting undocumented immigrants who have lived here for at least 10 years or who have children born in the U.S, at -37 and -36 points respectively. But deporting U.S. citizens convicted of crimes is only underwater by 14 points—in my view, an astonishingly weak negative considering the proposition of deporting American citizens. Holding immigrants indefinitely in detention centers sits at -4. You could say, “See! These moves are unpopular!” I find that insufficient.

I want to put forward a simple proposition: a country where such an administration and such behavior is only a little underwater is a deeply broken one. A country where over 40 percent of respondents could call what’s happening “exciting” is one where the animal instincts that undergird fascist politics are at the gates. A country that could re-elect him in the face of all he had already done and all he was threatening to do has shown a moral fickleness that ought to concern us moving forward. Trump is unpopular once more, and many of his policies don’t command broad support from the public, but I contend that he and his policies are not unpopular enough. This raises an existential question: is our civic virtue so spent that we cannot rescue the republic from the sewer it has fallen into?

That’s where the real rub comes. Because if we as a country are primarily moved by economic and personal financial pain, that suggests we do not mind so much if tyranny creeps into our system so long as we are prosperous. But liberal democracy can’t be sustained by prosperity alone, and it is not meant to deliver prosperity only. And if a few years are enough for us to forget an attempted coup and a mismanaged pandemic, we simply aren’t willing to give our democracy the attention it deserves. We are treating the most precious of things like an afterthought.

The entire enterprise of a free, fair, and open society depends on its citizens holding to higher principles and being willing to put those principles on the line. It demands that they not look the other way when individuals with such clear moral deficits as Trump promise quick solutions and easy riches. Scholars and observers of republican societies have made this point from ancient times to the present. A republic is only as good as its citizens.

Adamsian virtue, American vice

John Adams and John Quincy Adams, our nation’s first father-and-son presidents, spent considerable time contemplating the demise of Rome, both its republican government and its civic virtues.

They also wrestled intensely with the inherent vices of popular government.

Authors Nancy Isenberg and Andrew Burstein observe that both John and John Quincy “voiced what few politicians ever speak aloud: a conviction that the people are not always right, can be misled, and will arrive at conclusions with insufficient information.”

As John Adams wrote to his son in 1795, “It must ever be remembered that the mob is a part of the people, and I begin to fear the most influential part. The mob has established every monarchy on earth. The mob has ultimately overthrown every free republic.”

Both men encountered, in their time, the perils of demagoguery and populism to a republican government. John Quincy would see his presidency ended after one term with the rise of Andrew Jackson, a man whose prejudices and intemperate style the second Adams reviled.

As he defended himself against the Jacksonian assault, the sixth president declared:

The great object of civil government is the improvement of the condition of those who are parties to the social compact. Roads and canals are among the most important means of improvement, but moral, political, and intellectual improvement are duties assigned by the author existence.

What both John and John Quincy understood in their granitelike New England intellects was the fundamental frailty of human nature. At their most optimistic, they viewed the American project as a great endeavor in fashioning a people worthy of popular government and refined by the blessings of liberty. At their grimmest, they feared the total descent of the United States into tyranny at the hands of mob rule and the desolate instincts of demagogues and slavers.

But Americans right now seem to take our riches for granted and to approach liberty as merely a question of maximizing personal pleasure. At the richest moment in world history, in an unparalleled time of comforts and luxuries, we have elected self-harm and self-pity.

When people say MAGA’s success is good because they are now free to use the r-slur again; when a comedian like Andrew Schulz says what they like about Trump is that he sleeps around and doesn’t tell them what to do; when Americans can’t be bothered to pay enough attention to Trump to see the danger but can while away hours a day on TikTok and YouTube, that is a society in moral freefall. And it’s one where freedom is not an open door to mutual edification but rather a hall pass for personal gratification.

Liars’ republic

Jimmy Carter’s 1976 pledge was simple: I will never lie to you.

Carter’s one-term presidency is often portrayed as tragic, felled by OPEC and the Iranian Hostage Crisis. But the greatest tragedy of Carter’s national campaign is that his pledge to restore honesty to our politics proved quixotic. America’s elected officials only proved more dishonest in the decades to come, and the American people themselves came to be more morally accepting of lying as a habit of both public and private individuals.

In 2016, as Trump made his first successful bid for the White House, 64 percent of Americans said they believed lying to be “sometimes justified,” compared with 42 percent only a decade earlier. In the same poll, 20 percent of men said lying to their spouse about an affair is “sometimes or often” ok to do.

Scholars and fact-checkers alike have come to see lying as an epidemic in our politics. That’s the exact way that PolitiFact founder Bill Adair has described the crisis. Adair does put a greater weight of responsibility on Republicans, particularly the rise of Newt Gingrich in the 1990s, but he also stresses that Americans themselves don’t punish lying: “People are like, ‘yeah they’re lying, there they go again.’”

This is basically a distillation of the credibility gap, in which voters assume a level of habitual dishonesty from a politician or class of individuals. That electorate sees lying as inherent to politics and so doesn’t necessarily heavily punish individual lairs, including President Trump, poses a serious incentives problem. But it’s also a mortal danger to our political system because it represents a kind of immunocompromise. As former Representative Martin T. Meehan has written:

Those are good reasons to steer clear of deception, but lying on a grand scale by public leaders is even more alarming because it has the power to pervert public policy and even end lives. This is the point I made when I took on the tobacco industry as a member of Congress in the 1990s…the industry’s disinformation campaign took a massive toll. Public understanding was muddied, regulation was delayed, and many people got sick or died because of the industry’s desperate and deceitful tactics.

But Trump and his MAGA ilk aren’t merely prolific liars. They’re conspiracy entrepreneurs and malicious demagogues willing to go so far as to endanger their targets and opponents with defamatory attacks well beyond what was normal a decade ago. And the public is willing to internalize these lies and wield them against one another.

It matters, yes, that elites are misleading the people. But Americans are also more prepared to believe the worst about one another thanks to polarization. As such, we live in a golden age of conspiracy theories, with QAnon and The Big Lie driving a mob into the Capitol and anti-vaccine beliefs killing our neighbors and children. Yet dangerous conspiracy theories are not just pathogens tearing their way through a helpless public. Susceptibility to conspiratorial thinking is driven by complex factors like personality and life experiences, including trauma. Still, human agency matters, too. We have to participate in the adoption and spread of conspiracy theories.

The same is true of Trump and MAGA’s massive stream of lies that have so battered our republic. Yes, people are being lied to. Yes, our information environment is a Chernobyl-level disaster zone. But it’s also true that there is a market for these lies and the hatred’s that underpin them. There are people who want to hear and to believe the narratives that are offered up across right-wing media. And, of course, there are opportunists adding their own fuel to the fire in the hopes of enriching themselves.

We are all we’ve got

I have spent the bulk of this essay putting the American people through rather rough treatment. Now, I’d like to offer a salve.

Americans can choose a different fate. Our historical destiny is not written, and I believe wholeheartedly that the characters of nations and individuals are not fixed.

To quote Sarah Longwell, “It’s never too late to do the right thing.” Or, to quote Bill Clinton, “There is nothing that is wrong with America that cannot be cured by what is right with America.”

The fall of civilizations is only ever told from the point of view of history. We only get to live our lives in the all-too-narrow present.

We can come together and improve our condition. This will require individual efforts on all our parts, but it also demands a Putnam-esque resurgence in our civic participation. We have to know our neighbors and pull out the best from each other whenever and however we can. That’s the edifying, refining core of a free and popular government.

And we have to choose in the small, intimate moments of our lives those things that feed virtue: empathy, knowledge, curiosity, steadfastness. So putting down the phone or turning off the tv isn’t just a question of information or sleep hygiene, but of national order. Joining a cause or club is not just a matter of personal fitness, but of America’s vitality.

To close, I’ll let the elder Adams speak:

The only foundation of a free Constitution is pure virtue, and if this cannot be inspired into our people in a greater measure than they have it now, they may change their rulers and the forms of government, but they will not obtain a lasting liberty. They will only exchange tyrants and tyrannies.

Support Opposition Media

Featured image is César prêt à traverser le Rubicon