In Defense of “Yard-Sign Libertarianism”

"No Human is Illegal" is an ideal we can appeal to, however imperfectly it is put into practice.

The most striking image to come out of the Republican National Convention was, for me, the photographs of mostly white crowds holding up signs that read “Mass Deportation Now”. These were not fringe protesters infiltrating the convention; the signs were how the mainstream of the Republican Party chose to present itself. They held them up proudly while Texas governor Greg Abbott spoke of putting “criminal illegal immigrants” behind bars and the crowd erupted into chants of “send them back.”

I’m no longer shocked by anything coming from the MAGA movement, but I felt the ugliness of this moment viscerally: the wholesale rejection of America as a welcoming beacon for immigrants looking to better their lives and live freely, replaced by enthusiasm for a militarized police state that will shut our borders and round up millions of peaceful people for jail, family separation, or deportation.

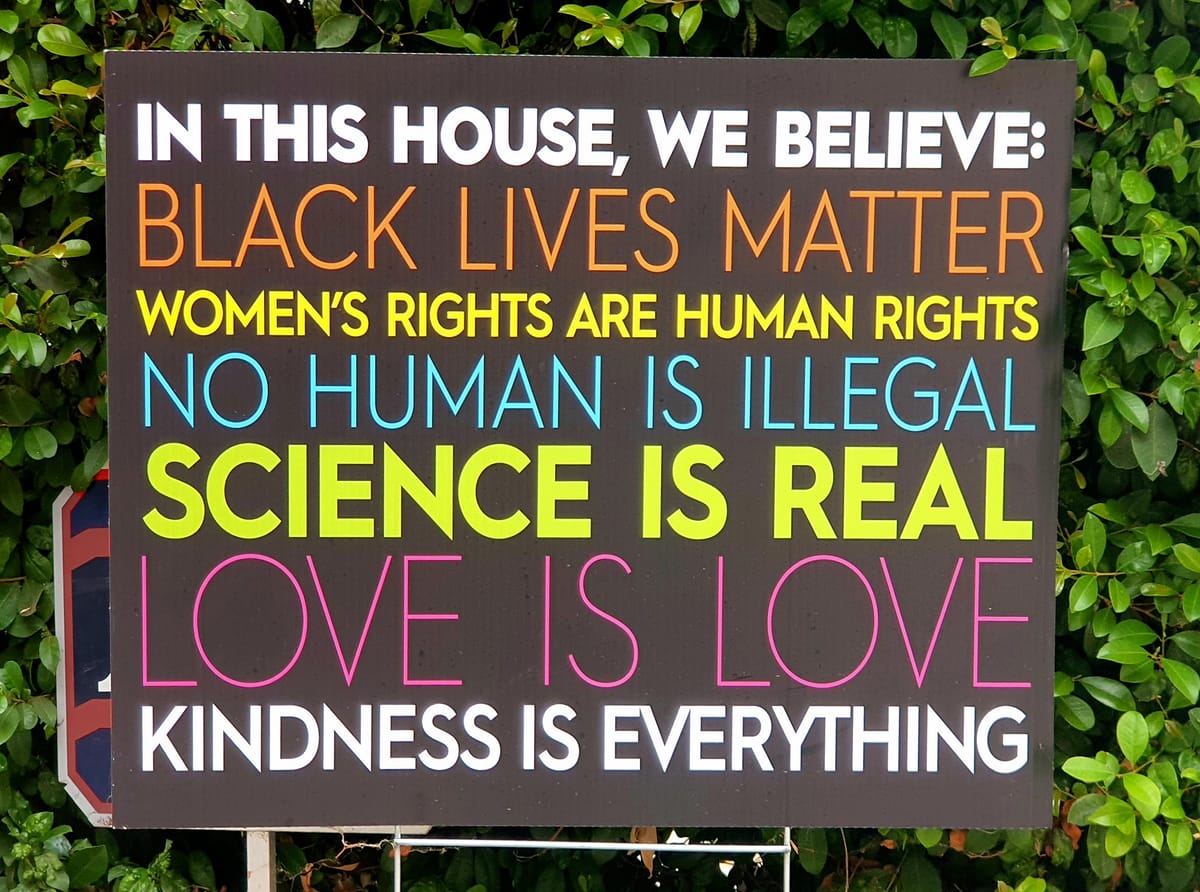

I thought of these signs again when I read Gene Healy’s response to my endorsement of the Harris-Walz ticket here at Liberal Currents. Healy, a friend and former colleague from my long-ago days working at the Cato Institute, criticized my take as an example of “yard-sign libertarianism,” his coinage for left-allied libertarianism, named after the “In this house we believe…” signs that have sprouted in the front yards of so many progressive households.

Living in Portland, Oregon, I’m no stranger to the ubiquity of these signs, nor to the various ways that progressives often fail to live up to the ideals they express. But considering the opposition, being grouped in with people who advertise their beliefs that “Black Lives Matter” and “No Human is Illegal”—two sentiments that libertarians should have no problem endorsing—doesn’t strike me as such a bad thing. And looking at the current state of the libertarian movement, I could certainly be in worse company.

Healy, to be clear, is not one of those libertarians who have gone all in on right-wing culture war grievances and denigrating immigrants. We agree on Trump’s unfitness for the presidency; he wrote in support of impeaching Trump and disqualifying him from future office following the events of January 6, and laments that significant parts of the libertarian movement have gone “full, barking #MAGA.” We’re also both well aware that neither Harris nor the Democratic party come close to perfectly embodying libertarian ideals. Where we disagree is on what stance libertarians should take toward this year’s Democratic ticket.

“More a ‘vibe shift’ than a competing ideological framework,” Healy says of yard-sign libertarianism, “the new orientation tends to privilege style over substance and presupposes that ‘left-wing cultural sensibilities [are] an essential part of the libertarian package.’” Ultimately, says Healy, this risks repeating the mistakes that fusionist libertarians have often made with regard to Republicans: allowing cheap talk about opposing big government to give cover to the numerous abuses Republicans enact whenever they’re in power. Better to remain clear-eyed and aloof than to allow team affiliation to cloud one’s vision. Healy writes:

I’m not sure how I ended up becoming a ‘professional libertarian.’ Quite plausibly, I should have done something else with my life. But looking back on what drew me down this path, I think it was a congenital affinity for ‘the first principle of libertarian social analysis’: skepticism toward power. Instead of joining a team, I liked the idea of (loosely) affiliating with people who didn’t care about politics and thought you should call things as you see them, without fear or favor. That is why I have zero interest in any version of libertarianism that reduces itself to an anti-Trump lifestyle brand.

There are a few threads to this critique and it’s worth disentangling them. One is about candidates’ prospective policies and how we should evaluate them. Another is about affect: if libertarians are going to support a major party candidate, should they do so with enthusiasm or distaste? A third is the implicit assumption that taking sides in one particular election impairs our ability to think critically as a policy analyst or political theorist.

That assumption is not unique to libertarians, and one should always be wary that team loyalty or self-congratulation may bias our thinking. If there is one lesson of the Trump era, it’s that team affiliation can lead one to excuse appalling things. One could say the same of, say, liberal complacence about drone strikes during the Obama administration. Abandoning standards for unprincipled loyalty to a candidate is a fast track to torching credibility and becoming a partisan hack. See, for example, the present-day Heritage Foundation.

But it’s also just not the case that enthusiastically supporting one candidate in a one election must put one firmly on their team in all contexts. Reasonable people are capable of holding multiple perspectives at once, approaching their role as voter differently than their role as, say, a libertarian policy analyst. It’s entirely possible to enthusiastically support Harris in the voting booth while retaining one’s intellectual independence to “call things as you see them” in blog posts and op-eds.

This brings us back to the question of affect. Healy doesn’t object per se to making a case for libertarians to vote defensively for a lesser evil. “But,” he writes, “as a libertarian, I can’t fathom approaching the task with genuine enthusiasm for either major-party choice—especially this year. The case for being a ‘double hater’ has never been so easily made.”

What irked Healy about my own endorsement was less the suggestion that libertarians should vote for Harris than that they should do so enthusiastically. For what it’s worth, I’m also perfectly fine with libertarians deciding to vote for Harris begrudgingly, if only to prevent Trump from returning to office. My libertarian case for Biden in 2020 was essentially such a lesser evil argument, predicated on Trump’s very unlibertarian first term, his inability to govern in a crisis, and the worry that he would seek to undermine the election. If that form of argument is more your cup of tea, you can pretty much substitute Harris’s name for Biden’s in my 2020 piece and come to the same conclusion.

But I do believe there’s a more genuinely positive case to be made for Harris and Walz. I outlined some of this in my earlier article, particularly their advantages on drug policy, immigration, and abortion. Following the Democratic National Convention, I think one can plausibly add YIMBY housing approaches to the list. It’s premature to conclude this will translate to actual policy, but it’s promising that ideas related to removing government barriers to production are taking hold among at least some elites in the Democratic party. To be a little more concrete, I’m persuaded by Robert Saldin and Steven Teles’s argument that there is fertile ground for an “abundance faction” to have an impact in Democratic politics. They write:

The table is set for just such a faction to emerge. But it won’t appear out of thin air. It will require deliberate action in the form of organizing, mobilizing, and engaging at both the elite and mass levels. Advocates of Abundance will need to pursue their agenda with the same kind of concerted effort that the MAGA movement and the democratic socialists have been willing to undertake. To borrow a slogan from the left, Abundance advocates will need to educate, agitate, organize.

None of this is a fait accompli; the future of Democratic economic policy is contestable and it could spin-off in more destructive directions. Yet contributing to the success of such a faction strikes me as a more productive use of libertarians’ political efforts than insisting on standing apart or, worse, aligning with the MAGA right, which has replaced even nominal support for economic liberalism with demands for deporting immigrants and imposing high tariffs. (As Josh Barro helpfully notes in a post about Harris’s vague proposal for an anti-price gouging law, “Trump has some economic ideas that are just as violative of Econ 101 as price controls, and that are a lot more likely to actually become public policy if he wins.”)

In his original post about yard-sign libertarianism and allegedly vibes-based analysis, Healy writes, “‘Politics isn’t about policy’ for most people, but it should be for libertarians.” I’m happy to make the policy case for Harris, though this framing is generally the wrong one for this election. When one candidate is committed to overturning the result if he loses, and has attempted such a coup before, debating the importance of, say, marginal tax rates is rather beside the point. Trump is so uniquely malevolent to the constitutional order that policy considerations become secondary. Making politics more about policy is yet another reason to root for a Harris victory: excising Trump is not a sufficient condition for renormalizing the Republican party, but it is a necessary one.

Yet even setting Trump’s dictatorial ambitions aside, it’s a mistake to dismiss “yard-sign libertarianism” as mere cultural affiliation. Publicly expressed sentiments do tell you something about what kinds of policies people are open to. Those of us who support radically liberalized immigration should be under no illusion that policy under Harris won’t continue to be ruefully inhumane, since that is the normal state of US immigration policy. But when trying to make progress on the issue, I expect to have more success with people displaying those “No Human Is Illegal” signs than the ones demanding “Mass Deportation Now.” The former presents an ideal that we can appeal to, however imperfectly it’s put into practice; the latter expresses eagerness to make things so much worse.

The baseline expectation for libertarians is that many of our ideas will be unpopular and that the state will be gratuitously cruel. That is not going to change overnight, but it’s no excuse for indifference to the outcome of the 2024 election. Faced with the real danger of an actual authoritarian in American politics, I am amazed by so many libertarians’ inability to rise to the occasion and proclaim their willingness to do the bare minimum to defeat him, namely voting for Kamala Harris.

Grit your teeth while you cast that vote, if you must. But I’ll also say to my fellow libertarians, you don’t have to be so damn dour all the time. No matter who takes office in 2025, I am sure they will give us plenty to complain about. But it will be far better to make those complaints about a normal Democrat than about Donald Trump. The right attitude toward this election, as expressed by another of my libertarian friends and former Cato colleagues, is to say, “I can’t wait to hold Kamala Harris’s feet to the fire and call out her every misstep as POTUS.”

Your vote is not a declaration of allegiance or an expression of your whole ideology. It is merely a recognition that one candidate presents some opportunities for progress, while the other is the most significant threat to liberty in recent history and a genuine evil to American democracy. That’s ample reason to vote enthusiastically for Harris and to celebrate her victory with your progressive neighbors, even if you find their yard signs annoying, at least for a few hours on election night. And then get back to working for a freer world.

Featured image is Yard Signs, by Slices of Light