If Reinhold Niebuhr Could Speak to Us Today, What Would He Say?

Democratic values must be actively cultivated and defended, or they will be captured and deformed.

About two years ago, after wrapping up a major book project, I found myself staring at my bookshelf, looking for new directions. I reached for John Dewey’s works, hoping to revisit 20th-century debates about the meaning and vitality of liberalism. Dewey’s aspirational vision of democracy and his faith in reason and education as transformative forces once felt illuminating. Turning back to him seemed wise in these politically unsettling times. As I began to read, Dewey’s words now felt strangely hollow as democracy itself bent under the weight of emergent authoritarianism. Yes, Biden was president, but Trump was coming for the office once again. Dewey’s words and philosophical vision didn’t feel wrong, exactly. Just passé for this moment.

As my eyes scanned the shelf, they settled on another figure: Reinhold Niebuhr. If Dewey was the champion of democratic hope, Niebuhr was its hard-nosed realist. They weren’t precisely philosophical opposites—each seemed to misjudge the other. But their focus and emphasis were different. Unlike Dewey, Niebuhr’s words seemed alive to history—especially in a time when the forces of cynicism and power-worship found new energy through Donald Trump.

Philosophical traditions aren’t just dusty relics. They shape how we see the world. They shape how we think about freedom, equality, and justice. And in times of crisis—when big things are at stake—they help us figure out what’s worth fighting for. Niebuhr understood that power is both necessary and dangerous, that moral clarity is often forged in the tension between high ideals and grim realities. And as I returned to his work, I found myself wondering: If Reinhold Niebuhr could speak to us today, what would he say?

Moral Man and Immoral Society: the limits of moral suasion

Niebuhr had been writing for some time before Moral Man and Immoral Society, but this was the book that drew me in—the one that felt like the right place to start. Originally published in 1932, Moral Man and Immoral Society is a foundational work in political realism, examining the tension between individual morality and collective power. In it, Niebuhr pushed back against two dominant strands of reformist thought: the Social Gospel, which envisioned moral progress as a natural extension of Christian ethics, and the progressive movement, which placed faith in democratic institutions and rational deliberation as engines of social improvement. Both, he believed, underestimated the depth of human self-interest and the structural entrenchment of power. He likewise dismissed Marxist expectations of a proletarian revolution emerging from the depths of the Great Depression. All such approaches offered a vision of salvation that Niebuhr found unrealistic and dangerously misleading.

Moral Man and Immoral Society was conceived in the shadow of economic devastation and global uncertainty. The Great Depression had shattered the liberal faith in market-driven progress, and the rise of totalitarian regimes in Europe was beginning to reshape the geopolitical landscape. The democratic order, already fragile, was under pressure from forces willing to exploit instability for power. It was precisely in that moment—when democratic institutions felt vulnerable—that Niebuhr issued his stark warning: neither moral reasoning nor procedural safeguards alone could hold back the tide of self-interest and power politics.

Nearly a century later, we face similar patterns of democratic erosion, economic anxiety, and the re-emergence of authoritarian tendencies under Trump’s leadership. For Niebuhr, figures like Trump are not anomalies but inevitable products of political life, where power is seductive and often wielded without moral restraint. Leaders, he argued, are rarely immune to the temptations of self-interest, and when unchecked, their ambitions can corrode democratic institutions from within.

Niebuhr establishes a realism worth attending to, emphasizing the inescapable role of power in political life. He argues that while individuals may act with a degree of morality in their personal lives, collective entities—whether nations, economic classes, or racial groups—operate with a different logic, one shaped primarily by self-interest rather than moral considerations.

Niebuhr’s key insight is that moral and rational suasion alone cannot resolve social injustice. We have seen this in real-time: despite Trump’s overt attacks on democratic institutions, too many political leaders have placed faith in procedural norms or conversational appeal, believing that the system and its norms will hold. But as Niebuhr warned, politics is not governed by pure reason or the fact of institutions—it is shaped by power, conflict, and belief. As he put it: “Contending factions in a social struggle require morale; and morale is created by the right dogmas, symbols and emotionally potent oversimplifications.” And Trump’s appeal has always been far more visceral, designed not to persuade but to solidify grievance into a political identity.

Yet Niebuhr was making a deeper point: even at its best, politics—democratic or not—can never serve as a vehicle for ultimate social salvation. Still, that does not mean resignation. The struggle for radical transformation remains necessary. Perfect justice, what Niebuhr often viewed as the great illusion, would forever elude our grasp, and yet we can’t help but make perfect justice our quest all the same. As he says:

It is a very valuable illusion for the moment; for justice cannot be approximated if the hope of its perfect realization does not generate a sublime madness in the soul. Nothing but such madness will do battle with malignant power and ‘spiritual wickedness in high places.’

He understood that while power must be confronted with power, a society incapable of aspiring beyond itself—driven only by self-interest—was doomed to reproduce its injustices indefinitely. Niebuhr’s realism, then, served as an antidote to naive optimism, even as he insisted that aspirational politics must not fall away. Social change demands both the hard pragmatism of power and the restless pursuit of ideals beyond immediate reach.

The Children of Light and the Children of Darkness: democracy’s fragility

The belief that democracy can sustain itself without an explicit contest for power is an illusion—one Niebuhr sought to dispel in his later reflections. If Moral Man and Immoral Society diagnosed the moral shortcomings of political life as such, The Children of Light and the Children of Darkness sought to chart a way forward in democratic politics. Written in the aftermath of World War II and amid the dawn of the Cold War, Niebuhr’s work grappled with the fragile survival of democratic institutions following fascism’s near-total victory in Europe. The world faced the task of rebuilding war-torn nations and ensuring that democracy remained resilient in the face of external and internal threats. At a moment when authoritarian regimes had proven their ability to harness mass support, Niebuhr’s insights were particularly urgent. His concerns feel no less pressing today, as democratic institutions struggle to withstand the pressures of nationalism, racial resentment, and cynical power grabs.

In The Children of Light and the Children of Darkness, Niebuhr elaborates on his understanding of democracy, rejecting both utopian optimism and cynical despair. Instead, he argues that democracy is the best form of government precisely because it takes human nature seriously. Democracy, he contends, is built on the paradoxical assumption that while human beings are prone to selfishness, they also possess the capacity for self-transcendence.

“Children of light” and “children of darkness” are shorthand terms for Niebuhr, representing political orientations that he claims inform and shape political actors. In Niebuhr’s view, the children of light are those who believe democratic progress is an inescapable development, supported by democratic means. This idea has taken many forms in American political thought, and one of its most recent expressions is found in the contemporary Democratic Party’s commitment to pluralism.

The 2024 presidential election made this perfectly clear. For many Democrats, pluralism wasn’t just an ideal—it was their game plan. Democrats assumed that demographic changes, coupled with the declining acceptability of explicit racism, meant that victory for a multiracial coalition was not just possible but inevitable. This assumption shaped Kamala Harris’s campaign: not that racism had vanished, but that it had become a politically manageable factor—too marginal to prevent the rise of a diverse coalition. The assumption was that the arc of American democracy naturally bent toward justice, that demographics were destiny, and that the very structure of democracy made a reactionary politics of exclusion unsustainable.

Niebuhr, however, was deeply skeptical of any vision of politics that rested on inevitability. While he was not immune to the idea that individuals and societies could strive for something beyond themselves, he knew that democratic progress was never simply a function of time—it required the contestation of power. He understood something that many of today’s Democrats fail to grasp: history does not bend toward justice on its own. Without a counterforce that actively channels the anxieties and aspirations of the public, the forces of reaction do not fade—they regroup, recalibrate, and return with greater force.

Today, Niebuhr’s warnings about forces that regroup and endanger democracy feel eerily prescient. Trump’s return to power represents the persistence of authoritarian tendencies within American life and the failure of democratic institutions to check these forces adequately. Trump’s rise was not the product of economic anxiety or cultural grievance alone, but their toxic fusion—where fears of economic decline were weaponized into racial resentments, and democracy itself was hijacked as an instrument for exclusionary power. As Niebuhr warned, democratic institutions are both the cause and consequence of cultural pluralism. Yet, their openness can also be manipulated to restore what he calls a “primitive unity,” one that suppresses difference through coercion. Trump’s current use of executive orders and the unchecked workings of the Department of Government Efficiency are only the beginning of a broader system of coercion under his administration.

Niebuhr’s relevance in the Age of Trump

Niebuhr would have recognized Trump as an embodiment of the “children of darkness,” a leader who wields power without regard for justice. Yet in today’s political climate, such descriptions may seem overly stark, as if they reduce his influence to mere villainy rather than addressing the forces that sustain it. These forces—economic uncertainty, racial anxieties, and the manipulation of public grievance—have been central to his rise and his ability to reshape the political landscape.

His presidency, particularly in its second term, is marked by a radical erosion of democratic norms, an embrace of cruelty as a political tool, and a disdain for accountability. Instead of confronting economic hardship directly, Trump exploits it, redirecting frustration into cultural resentment and turning marginalized communities into convenient targets. His messaging finds fertile ground in a media landscape dominated by outrage and division. As Niebuhr noted:

The peril of disharmony from such variety is always so great and the pride of a dominant group within any community is so imperious, that some effort is always made to preserve a coerced unity, even after the forces of history have elaborated multifarious forms of culture.

The struggle over diversity is as old as America itself. As President, Trump taps into anxieties about the browning of America to fuel a resurgence of white supremacy. He uses this fear to reshape the meaning of law, targeting educational institutions for so-called 'reverse racism'—claiming that Black and Brown students are given an unfair advantage over white students.

But the law is just one tool. The deeper battle is cultural. Across all federally recognized or federally funded institutions, his goal is to erase an ethos that once encouraged awareness of racial and gender exclusion. He aims to reframe racial and gender affirmative policies as an assault on freedom and equality. This is the political playbook: take progress and make it feel like oppression. Tell white conservative men that every gain for others is a loss for them. This isn’t just political maneuvering—it’s the ideological heart of Trumpism. And it works because power, left unchecked, is always liable to bend toward domination.

If Moral Man and Immoral Society teaches us that justice requires the mobilization of countervailing power, then The Children of Light and the Children of Darkness reminds us that democratic values must be actively cultivated and defended, or they will be captured and deformed. Trump’s presidency thrives on exhaustion and despair; it depends on people surrendering to cynicism because resistance and fighting seem to mark the failures rather than the beginnings of democratic politics. Niebuhr offers a different vision—one that acknowledges the depth of the crisis but refuses to give in to nihilism and does so because democratic politics is about fighting for better forms of life.

Criticizing Trump and the Republican Party does not necessitate naivety regarding the failures of the Democratic Party. The Democrats have not consistently prioritized the economically disinherited—a class that transcends race—in their pursuits. This, of course, stems partly from their own closeness to an economic oligarchic class. However, the Democratic Party is less cruel and vicious precisely because it allows for criticism of its organizing and power usage. It is the very role of criticism in a democracy that President Trump is swiftly attempting to undermine or demonize.

The task ahead: power and moral clarity

Niebuhr’s insights suggest that the task ahead is twofold. First, a concerted effort must be made to build and sustain movements capable of challenging authoritarian power. This requires political organization, strategic resistance, and an acknowledgment that conflict is inevitable. This means that Kamala Harris would do well to come out of the shadows and stop performing the rituals of American-style democratic politics, where the loser retreats into relative obscurity. Unusual times require that we put rituals aside and stand for what we believe in even amid defeat.

Second, there must be a renewed commitment to articulating and defending democratic ideals. Democracy is not self-sustaining; it must be continually reasserted in the face of those who seek to undermine it. This must be done by tying the violation of democratic ideals to the lives of everyday citizens. The stories of illegitimately fired federal workers, of the anxiety plaguing children suspected of being “illegals,” and of the instability produced in the lives of ordinary Americans must be pushed into the foreground. What ties their stories together, even when affected by different agencies of the American government, is that they all result from the cruelty of the existing administration.

I did not anticipate just how illuminating Niebuhr would be—especially at a time when the Democratic Party is not so much lost as struggling to understand that whatever path it takes must be anchored in the realities of power. Meanwhile, the Republican Party is successfully fusing power with a vision, however regressive, wielding it as a coherent and winning strategy. The echoes of fascism are not just in Trump’s rhetoric but in the very logic of his movement: the belief that democracy’s fractures should be exploited, deepened, and ultimately 'resolved' through racial, cultural, and economic homogeneity. As I return to Niebuhr’s work, I keep thinking: Are we ready to hear what he would tell us? And if we are, what are we going to do about it?

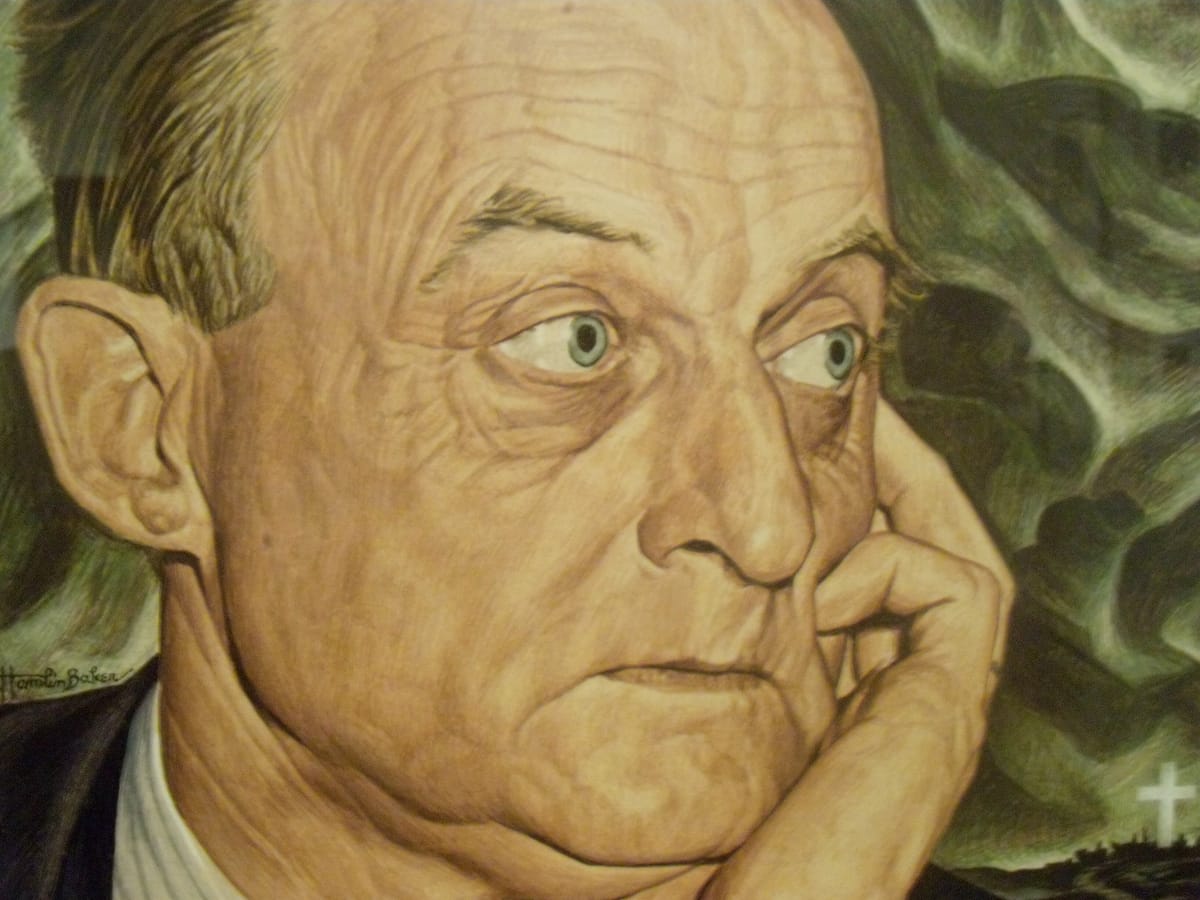

Featured image is portrait of Reinhold Niebuhr, by Ernest Hamlin Baker