How to Decipher Propaganda

Discourse studies is an interdisciplinary method used to unpack how we use language to organize and express ideas in the most convincing possible way, even up to the point of misleading our audience. To illustrate how useful Discourse Studies can be for getting a deeper understanding of the messages around us, I analyze the conservative watchdog group Campus Reform as an example. The following is adapted from a talk I gave at the annual conference of the Linguistic Society of America.

The study

For this study, I took a sample of stories from Campus Reform to analyze. A project of the Leadership Institute, Campus Reform’s mission statement says it is “a conservative watchdog to the nation’s higher education system.” Its homepage is designed like a news site, with featured stories and videos arranged into sections such as “Trending,” “Opinion and Analysis,” and “Editor’s Picks.” Founded in 1979 by its president Morton C. Blackwell, the Leadership Institute “recruits, trains, and places conservatives in government, politics, and the media” in order to “increase the number and effectiveness of conservative activists.” Political scientists McCarthy and Kamola argue that Campus Reform authors engage in “sensationalized surveillance,” the practice of searching out and spotlighting those who offend the conservative sensibilities of its readers, portraying their work in the most upsetting possible light, so that readers will be inspired to contact the subjects and their employers to try and influence them to impose sanctions.

In a report for the American Association of University Professors, Tiede et al. (2021) found that being targeted by a Campus Reform story has a tangible effect on instructors, especially young and underrepresented ones, triggering significant amounts of harassment and threats against them and even losing some of them their jobs for the crime of self-expression.

Knowing all of this, and since my research interests have come to revolve around how established, well-known figures wield phrases like “academic freedom” and “cancel culture” as weapons to silence those who might discredit the views on which they have built their careers, I wanted to take a magnifying glass to one of the organizations whose material is regularly linked by such figures. This was a preliminary study to find out whether any patterns would emerge in terms of the kinds of stories Campus Reform would put out in a given time period, how they used genre to create a sense of legitimacy, and what linguistic tools they used to accomplish their mission. I took snapshots of the home page from a few days in March 2021 and analyzed the text in all the stories they promoted on those days.

Thematic coding

One of the first things I do when I’m starting a Discourse Studies project is to read through the data and start marking when certain topics or phrases get repeated. The themes I found were almost exactly as I expected: stories highlighting a professor who said something leftist, highlighting student organizations or newspapers who said something leftist, schools bowing to leftist student demands, stories about cancel culture, and stories about antiracism or DEI efforts (diversity, equity, inclusion). I thought there would be more about Critical Race Theory, which is well-represented in political discourse during the time frame of the data, but Campus Reform was more interested in the broader concept of DEI.

A theme that asserted itself across all these topics was the use of news discourse to make this watchdog organization’s missives seem more like journalism.

The discourse of news

One of the first things that stood out to me was the use of discourses associated with the genre of “news.” There is a lot of material on the internet that is not news but does significant discursive work to look like news because of the credibility we associate with journalism. Look at any mainstream news website and you will see a particular visual language. At the top there will be a headline in bold, a large image, information about the author and when the story was published.

In the body of the story the paragraphs are short, sometimes just one sentence long, and between them there are links to related stories to keep the reader engaged.

Toward the end, a statement appears about the efforts the news organization has made to represent all perspectives in the story. At the end, there is a call to action designed to increase your visits to the site. The CNN story encourages you to sign up for updates on news concerning the topic of the story you have just finished:

And the Campus Reform article asks you to follow the author on social media by linking you to their author profile, which lists ways to do so.

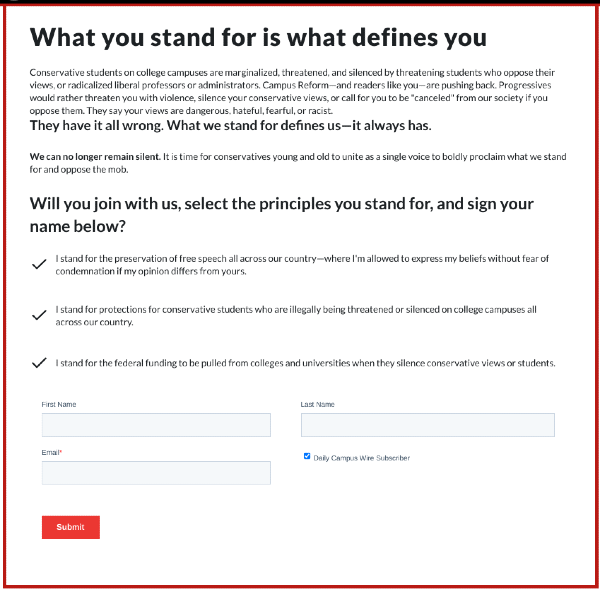

At the very bottom, all Campus Reform articles ask you to sign up for emails and sign their pledge, which affirms free speech as freedom from “condemnation,” reasserts that conservatives are being discriminated against on college campuses, and demands the defunding of public universities where Campus Reform believes conservatives are being silenced. This pledge looks like the newsletter sign-ups that appear at the bottom of many online news articles, and it does also sign you up for a newsletter, but the language in the pledge is closer to what would appear on activist organizing websites than on news sites.

Beyond the visual language of news, there are certain key words and phrases that remind you of other news you’ve seen before and thereby convey the sense that what you are reading now is another example of conventional news. For example, we are used to seeing words like “EXCLUSIVE,” “BREAKING,” and “REPORT” at the beginning of headlines. Subjects of stories are “reached for comment” and updates are promised as the story “develops.” All of these linguistic features are present in stories by Campus Reform, suggesting an effort to replicate the discourse of news. Incidentally, despite nearly a year having elapsed since this data was collected, none of the stories have been updated, even if new information has surfaced.

Even the grammar of news is recognizable. As readers, we have become used to the concept of “headlinese,” a topic of interest to linguists since the 1960s. In his 1967 paper, Halliday called it “economy grammar,” because when we consumed only print news, there were constraints imposed by the physical process of printing newspaper pages. Function words like “the” and “a” were discarded for space, creating an elliptical and telegraphic grammatical style that we still see today, even though the practical reasons for its development no longer obtain. It’s become convention.

The tool of “newsworthiness”

One of the main questions in the study of news is what stories make it to publication. The fact of a story’s publication implies to us that it is “newsworthy,” but what are the actual qualities that make something newsworthy? We tend to agree that something is worth being printed as a news story if it could impact us or people in our proximity, if it is timely, if it shows something about humanity, if it serves as an example of a developing trend, or if it involves notable people. In Teun van Dijk’s Racism and the Press, van Dijk argues that publications may take advantage of our assumptions about newsworthiness to take negative stories about individual members of a culturally maligned group and imply that they are representative of a larger pattern in society. As readers, we will see stories about professors doing something not particularly noteworthy, see all those discursive cues that what we are reading is news, and interpret it through a filter that assumes “newsworthiness.” The result is that readers will try to figure out how that story could be impactful, timely, or emblematic of a larger pattern. My data set included quite a few such stories, like this one:

Why would a panel on antiracism in which a positive statement is made about the Black Panther Party be news? The story just gives short quotes without much commentary, allowing the existence of the statements alone to speak for their newsworthiness. Someone who is sympathetic to popular antiracist thought such as the kind professed by Ibram X. Kendi might read this article as neutral, except for the fact that it is considered a story at all. That fact is what van Dijk had in mind when he described the effect of reporting non-newsworthy events.

Somewhere in the middle of the story is buried the context for the original statement about the Black Panther Party. The professor in question was specifically expressing respect for the “Free Breakfast for School Children'' program and how its success led the USDA to create a similar program nationwide. Why this merited headline treatment is again left to the interpretation of the reader, who must search for a reason. Stanley Cohen’s 2011 book Folk Devils and Moral Panics discusses the way popular press amplifies moral panic via “deviancy amplification”—each iteration of a story emphasizes misperceptions to reinforce the reader’s belief that serious deviance is taking place.

Inconsistent hyperlink practices

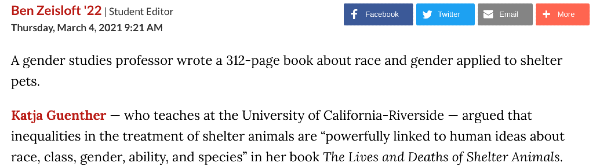

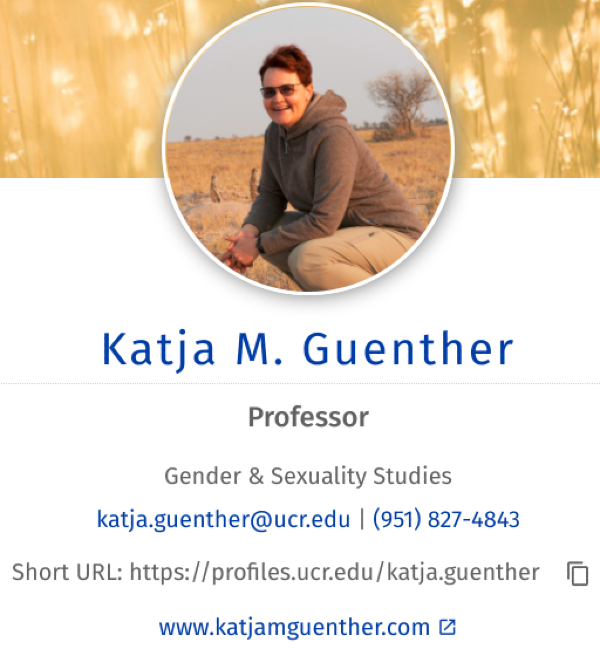

Another subtle way Campus Reform encourages the harassment of certain instructors and not others is the way they tend to handle the hyperlink in the sentence introducing that character. For example, in a story whose only purpose is to draw readers’ attention to a radical professor who thinks pet adoption trends might be socially mediated, the first time her name is mentioned, it is hyperlinked to her staff profile page, which includes multiple ways to contact her:

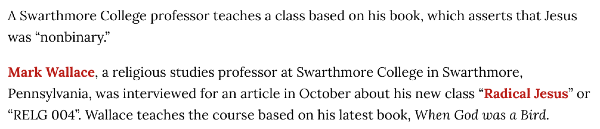

In the story about the professor who teaches about various treatments of Jesus in religious studies (which Campus Reform presents as simply teaching that Jesus was nonbinary), the hyperlink goes to his contact information as well.

This may seem unremarkable—why not link to a professor’s staff profile when discussing that person?—but when Campus Reform reports the words of a professor whose perspective more closely aligns with their own, the hyperlink attached to his name takes the reader to the Bing search results, which prioritizes shopping for his books.

In subtle ways, Campus Reform uses practices inconsistent with professional journalism such as the hyperlink issue, failure to provide updates where promised, and small linguistic cues to stance in order to function more like a conservative activist organizing group than like a journalistic endeavor.

Epistemic stance

In sociolinguistics, we use “stance” to refer to the ways we use our words, tone, and other paralinguistic features to indicate our own views. One of the ways we can do that is through words that convey epistemic stance. Imagine prefacing a proposition with “some people believe that X.” In doing so, you suggest that you’re not necessarily endorsing X; in fact, it might be a widely-believed myth. If you instead say, “It’s a widely-known fact that X,” you’ve now endorsed the factual basis of the proposition X. The difference between those utterances is one of epistemic stance.

Another useful thing to look at is verba dicendi, or the words that authors used to introduce the speech of their subjects. I found that professors positioned as left-wing or “woke” were most likely to “claim” or “explain” things, whereas professors or researchers who were ideologically aligned with Campus Reform were more likely to “tell,” “find,” or “reveal.” Similarly, when I looked at the noun phrases used to introduce those subjects, left-wing professors were often introduced with no title or a partial title, whereas right-of-center figures were given their full title and even added descriptors like “expert” or “leading.” This practice gives a strong sense of who Campus Reform thinks should be believed.

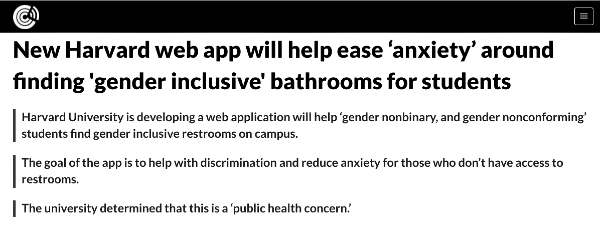

Another way Campus Reform showed a negative epistemic stance was through the use of scare quotes. The author of this story, for example, is using “anxiety” and “gender inclusive” in a way that indicates that they do not endorse the content.

Coddled leftist students

In the data set I examined, a stark pattern stood out in which the preferences and concerns of students positioned as left-wing were treated as frivolous, demanding, and ridiculous, and institutions were painted as bending to their whims. This is another type of stance, referred to as “affective stance,” in which the authors transmit their opinions of the people and propositions at hand. As an example, here is a detailed look at one story from the data set.

The scare quotes indicating the author’s epistemic stance give the reader a hint about how legitimate they perceive the UMich Students of Color Liberation Front to be. The organization submitted a list of several demands, but the headline lists only a demand about hummus and Israel trips, and the hummus is the header image. The letter actually does not mention Sabra (or any other hummus brand), nor does it demand an end to Israel trips, but it does contain many other demands, including protections for student free speech rights and requests to update pedagogy and curricula in specific ways, citing significant research and experts.

The fact that Campus Reform is assuming their readers will want to hear about the goofy student group angry about hummus (as opposed to the concerned students who are asking for more balanced teaching and free speech protections) conveys an affective stance that student groups interested in social justice are hysterical, authoritarian, and unintelligent, and that their problems are insignificant.

Campus Reform asked for comment from a university spokesperson and received a response affirming that the university is meeting with SOCLF to understand their concerns and maintain an ongoing discussion about how to address them—this response is provided without commentary. Newsworthiness suggests that this is a noteworthy response or emblematic of a pattern that should be of concern to the reader. This story is joined by quite a few others in which the mere fact that a university administration gave any attention at all to progressive student concerns was treated as a problem.

In the story, Campus Reform takes advantage of metonymy, using “the demands to remove Sabra hummus, end Israel trips, and eliminate cooperation with ICE” as if it were a complete synonym for the demand letter. Putting aside that the first two demands do not appear in the letter at all, the third one doesn’t appear until page 8 of the document, as it is only one of many policy changes the organization considers beneficial to the students of color on the UMich campus. These three demands, while not remotely representative of the whole of the document, stand in for the document throughout the story.

The hummus and Israel trip demands—were they real—would fit into a left-right split on attitudes toward the Israeli-Palestinian conflict. Though ICE is the least popular federal agency in the U.S., there is a large split along partisan lines. Campus Reform may be relying on that partisanship to predict that their readers will be pro-ICE and will consider the SOCLF’s concerns about supporting the Israeli government and jeopardizing undocumented students’ safety to be unreasonable.

Persecuted conservative students

At the same time that leftist students are being treated as frivolous, demanding, and coddled by their institutions, Campus Reform also produces stories that present conservative students as oppressed. One type of persecuted-conservatives story is one that repeats the conclusions of reports produced by libertarian or conservative think tanks, which give the impression that conservative students are under attack.

The first “study” was actually a non-peer-reviewed report produced by a think tank called the “Center for the Study of Partisanship and Ideology,” whose founder and president is Richard Hanania, a former Columbia fellow who has been criticized for racist statements. The report is written by Eric Kaufmann, a professor of Politics at the University of London. His most recent book, Whiteshift: Populism, Immigration, and the future of White Majorities, blames the rise of populism in Europe and North America not on white nationalism and anti-progressive backlash, but on the “anti-white ideology of the cultural left” and recommends appeasing far-right concerns about racial replacement, a conclusion that is not supported by the empirical findings in the book and has caused him to be criticized as an ideological reactionary. Kaufmann’s primary brand over the last few years is finding new ways to justify the reactionary (sometimes branded as “classical liberal”, for better or worse) belief that academia is a leftist indoctrination machine, intolerant of any other perspectives. It is therefore no surprise that right-wing organizations tend to fund these projects.

The second study was at least an actual study, but the headline gives the impression that it found bias in the behavior or attitudes of biology professors. It is not a study of biology professors, but a survey of Christian biology students who felt discriminated against. The first author of this paper, with others, acknowledges in this and another study that Christians are more likely to perceive that their group will be discriminated against than professors are to actually discriminate. Negative feelings of instructors tend to be limited only to the most fundamentalist varieties of Christianity, but they do exist.

Another type of “conservative victims of discrimination” story will focus on a single student who felt discriminated against for conservative views.

Anecdotal stories of anti-conservative discrimination were characteristically low-stakes: in this case, a student lost some points on a single essay, which she got back when she asked her professor to review the assignment. The student had written an essay about the New Black Panther Party (NBPP), which is described by the Southern Poverty Law Center as violent, anti-semitic and anti-white. The teaching assistant, whose definition of “racism” differed from that of the professor, mistakenly assigned the grade according to their own definition, which limits the concept to exclusively systemic racism.

Since the issue had already resolved itself immediately and the conservative student did not actually suffer a lower grade for her view that the NBPP was racist, the story about her was necessarily quite short. Appended to the end of it is this unrelated anecdote from a student at the same school:

This is the extent of the story on Ricco, whose claims were not investigated or questioned by Campus Reform, nor were any details provided to substantiate his claim that his low grade was the result of his conservative beliefs rather than poor scholarship or a failure to meet the requirements of the assignment.

There is also a notable discrepancy between the story’s headline, which mentions “Black Panther”, and the story itself, which was about the New Black Panther Party. The NBPP was founded by people who had not been affiliated with the original Black Panthers, and has been denounced by surviving Black Panther members. The omission of the word “New” from the headline contributes to a pattern of painting any positive sentiment toward the Black Panthers as wrong and worth alerting the public to.

A third type of story that contributes to the overall sense that conservative students are discriminated against is the radical professor trope. In these stories, the only content is a description of a left-wing statement or program being run by an instructor, student group, or institution. The BYU professor who “paid respect” to the Black Panthers’ breakfast program is one such story. These radical professors are portrayed as at once strong and weak: they have a concerning amount of power, but their efforts are laughable, unfounded, and unpopular. This headline helpfully demonstrates both at once: we should be worried about the “plot” and the “strategy” of these professors, we should be alarmed by the violence of “smashing,” but also we should laugh at how silly it is to worry about pancake syrup.

We can see this tendency in the quotes given by Campus Reform allies as well. In a story about the Stanford College Republicans not having their letter published in the student newspaper, the SCR student representative both describes what happened as representing a “concerning trend” in which students approve of “stifling any and all healthy debate and civil dialogue” but also makes sure to point out that it’s a radical fringe perspective, and that they actually have the support of “Stanford students on the right and center-left.”

Academic freedom, viewpoint diversity, and cancel culture

The majority of stories in this data set revolved around these themes. As I have discussed above (and in my other articles for Liberal Currents), the concept of academic freedom has been twisted and manipulated to punish progressive self-expression and elevate the profiles of those who advocate for conservative values. One way to achieve this is to publish misleading and cherry-picked data that suggests that the only “safe” opinion to hold on campus is a narrow band of far-left views. In environments such as these reports describe, viewpoint diversity is impossible due to left intolerance, and the various consequences of violating the left-wing orthodoxy that threatens academic freedom are described as cancel culture.

The term “to cancel” originally meant to dump someone or stop being their friend, but the more recent meaning comes from Black Twitter, and is defined by Media Studies Assistant Professor Meredith D. Clark in her paper as “an expression of agency, a choice to withdraw one’s attention from someone or something whose values, (in)action, or speech are so offensive, one no longer wishes to grace them with their presence, time, and money.” Clark points out that the diffuse and imprecise application of “cancel culture” to any criticism of elites and institutions represents insecurity on the part of those institutions that there is no longer one public sphere of discourse which they can control, and their panic that the words and desires of previously silenced groups can now be disseminated in one of the many public outlets that now exist in the digital age. Rather than admit that the moral panic around “cancel culture” is an attempt by elites to protect their own status, they invent ways to sell it to the public as a real threat to the average person by compiling cherry-picked lists of low-stakes, often consequence-free “attacks” such as the one compiled by the Foundation for Individual Rights in Education. I discussed several of the issues with that database in my article on Peter Boghossian.

This diffuse and inconsistent application of “cancel culture” is clear when we list the various events that are described in Campus Reform stories as examples thereof:

- A student newspaper rejecting a letter from Campus Republicans replying to an article that points out ways a student group has violated campus policy without consequences (also known as “leftist fascism”)

- A professor on paid leave while being investigated after calling reparations “bullshit” on Twitter (the article)

- Students asking their school to stop playing a minstrel song at football games (the article)

- Football players leaving the field when their school insists on playing the minstrel song (but not when wealthy donors threatened to stop giving money if the school complied; this is saving the song from cancel culture)

- People being afraid to “get insulted and expose [sic] in the public square,” according to the Premier of Quebec

- The rise of “certain social science theories,” also according to the Premier

- An “intellectual matrix from American universities” and “certain social science theories entirely imported from the United States,” according to Emmanuel Macron

- “Anglo-Saxon traditions,” also according to Macron

- A trend of “unacceptable silencing and censoring,” according to the UK Education Minister

- “American academic ideologies” (in the header of the same article)

- Student activists writing a list of demands including reviewing how Palestine is taught, protecting the free speech rights of students, banning ICE agents from campus

A worrying number of the things being called “cancel culture”—a phenomenon which is supposed to be synonymous with silencing people—are actually examples of self-expression. Examples of students writing letters, football players seeking some control over what song they are introduced with, and the bare existence of “American academic ideologies” or “certain social science theories” (reasonably interpretable as being a reference to Critical Race Theory or Identity/Area Studies) show how the concept of cancel culture does not even require that speech be subtracted. The wrong kind of speech can still be called cancel culture.

Curiously, the story of a professor being fired for referring to Mike Pence as a demon on Twitter—reporting of which originated on Campus Reform and was disseminated throughout conservative media—did not qualify as “cancel culture” even though her termination took place after pressure from Campus Reform readers and the county’s state representative, and even though she won a lawsuit against her college for wrongful termination.

Events or concepts that qualify as a violation of academic freedom, according to the stories in this data set:

- Everything in the “cancel culture” list, including “cancel culture” itself

- Professors having views that challenge conservative ideas about race, gender, class, disability

- From the CSPI study:

- Some academics saying they wouldn’t hire a Trump supporter or a Brexit supporter

- Most academics not wanting to have lunch with someone who has bigoted views about trans women

- Only “most” academics not supporting “cancellation” of academics who publicly state things like that diversity is bad, women and minorities are low performers, or “empire” is positive

- Trump/Brexit supporting academics not feeling comfortable telling a colleague about their support

- Conservative students feeling their politics don’t fit academia

- Most academics (in certain disciplines) being left or center-left in their politics

- Students’ perceptions that Christians will be discriminated against in biology

- Students no longer being forced to contribute money to anti-LGBT+ clubs that also happen to be religious

- A student losing points on an essay, then getting the points back after she complained

- A student saying he is seen as a nazi and a racist for expressing unspecified conservative beliefs in class, losing points for supporting the second amendment in a research paper

- An academic journal adding an optional space for submitting authors to explain how they contribute to inclusion and diversity in their field

After listing the types of events that are called cancel culture or threats to academic freedom, I looked for patterns in the lexical items that accompanied the actions of the people deemed responsible for these offenses. Many of the examples listed may not seem terribly urgent, but the language used in the stories tends to exaggerate the peril conservative students face. The authors use words like “plot,” “attack,” “fascism,” “authoritarianism,” and “discrimination” to give a sense of urgency to the stories so that readers will feel moved by a sense of impending danger to take action.

Conclusion

In a time when those who wish to curb the freedoms of our educators are couching their wishes in “transparency” to hide the mechanisms of censorship, watchdog organizations like Campus Reform play a significant part in enabling those efforts. Across the United States, laws are being passed that prohibit teaching Critical Race Theory, books and educators are being removed on suspicion of sneaking it into classrooms, discussion of LGBTQ+ experiences is forbidden from even being broached in some schools, books about the Holocaust are being removed from curricula ostensibly because of mild cursing and nudity, and those at the forefront of such moral panics are using the momentum to reduce the prevalence of public education. Students are also coming forward to discuss the ways their academic progress has been diverted and even halted by sexual harassment, abuse, and institutional indifference, as well as the way abusive professors use their status to cut off avenues of support for their victims.

At the same time, a significant number of well-funded think tanks are creating more and more reports and sharing low-stakes or false anecdotes that give the impression that universities are intolerant of any viewpoints or research that do not align with a far-left ideology, and these reports and anecdotes are shared by people from the extreme right to the center-left. The belief that left-wing bias in universities poses a real threat that we need to confront is not uncommon, but data just doesn’t support it. The unmaking of the public university continues apace, and it is being helped along by high-power academics and others who are able to weaponize the prestige and apparent trustworthiness of academics and journalists.

What my analysis does—and the reason I do discourse analysis on issues of academic freedom and cancel culture—is show the specific, subtle ways that propagandists don the trappings of journalism and research in order to mimic the discursive features we are used to from those genres while not doing the required work and due diligence that manifest their rightful authority. Campus Reform may look like a journalistic project that happens to have a mission, but it is more like an activist action list wearing journalism’s clothing. The more credence we give such projects, the easier it is for them to accomplish their project of destroying the public perception of higher education.