Existential Liberalism: James Baldwin and the Problem of Freedom

The burden of freedom has always been heavy, and Baldwin forces us to confront whether we are willing to bear it.

Freedom is among the most celebrated words in the American moral and political lexicon. But what if we always misunderstood it? Or, at least, what if we misunderstood that freedom is not just a gift, but a demand many refuse to bear?

James Baldwin understood this tension better than most. Years ago, as a graduate student at Yale University, I remember reading his words—sharp, unrelenting. I wasn’t ready to fully immerse myself in his writing; we can sometimes come to a thinker too soon, ill-prepared for what is on offer. But I do remember how his words struck me. They strike me now, just as fierce, just as true:

Freedom is hard to bear. It can be objected that I am speaking of political freedom in spiritual terms, but the political institutions of any nation are always menaced and are ultimately controlled by the spiritual state of that nation.

Baldwin’s insight is as urgent today as it was then. We live in a moment where democracy is in crisis—not just in its institutions, but in the character of its people. The burden of freedom has always been heavy, and Baldwin forces us to confront whether we are willing to bear it.

Baldwin was writing as World War II ended and the Cold War began. It was a time of self-congratulation, a moment when the United States styled itself as the moral center of a newly ordered world. But beneath that self-image, something was shifting.

The meaning of freedom was changing.

Earlier generations, particularly those influenced by the Social Gospel and Progressive movements of the late 19th and early 20th centuries, defined freedom as a moral and civic responsibility—a task of shaping character and preparing citizens to live democratic lives. But in the postwar period, freedom was increasingly defined negatively: freedom from external threats, state interference, and instability. Arthur Schlesinger’s The Vital Center of 1949 captured this shift: the Cold War transformed democracy into a bulwark against communism, making security its highest promise.

But this postwar shift coexisted with an older, regressive tradition. White supremacy had always been its own kind of security blanket for white Americans. Even as the progressive movement sought to regulate industry and expand democracy, for example, it remained bound by the racial exclusion of Jim Crow. As Thomas Leonard shows in his extraordinary text, Illiberal Reformers, progressives sought to help “the people,” but that category often excluded African Americans.

The fear of instability was not just geopolitical; it was racial. Even as liberal democracy claimed to champion freedom, whiteness remained a competing force, shielding white Americans from reckoning with the full implications of their professed values. Baldwin understood that this contradiction always haunted the nation’s democratic aspirations—freedom was celebrated in the abstract but denied in practice to those whose very presence threatened white supremacy.

This tension has not disappeared. Even today, political discourse is suffused with fears about instability—about who belongs, whose votes count, and whose freedom is seen as a disruption rather than an expansion of democracy. The very idea that democracy should be a site of struggle, rather than a settled inheritance for one group, remains deeply contested.

Samuel Moyn has recently lamented that postwar liberalism broke with an earlier aspirational version. But the persistence of racial inequality reveals a deeper truth: both versions were defined less by their ability to improve the citizenry and more by their efforts to shield some from the demands of freedom made by others.

Baldwin wrestled with this anxiety about freedom early on, particularly in Notes of a Native Son, a collection of essays written throughout the 1940s and 1950s. In it, he traced the workings of race—not just in America but also in Europe and, above all, in himself.

The Civil Rights Movement was underway, pressing the United States to honor its commitment to freedom. Race was everywhere etched into laws, governing interactions, determining destinies. Yet, for Baldwin, race was not just a social reality but a psychological one. In white Americans, it functioned as a spell, an incantation against deeper fears.

Race was meant to settle something in us, to act as a sign of permanence, a shield against the fundamental instability of identity itself. For if African Americans were inferior, as white Americans so often assumed, then whiteness could rest secure—fixed, stable, ordained. Baldwin exposed this preoccupation and with it laid bare the more important question: Who are we beyond the myths we have constructed?

Baldwin’s discussion of race is so central that it can obscure a more fundamental concern. “Every society,” he tells us in Nobody Knows My Name in 1961, “is really governed by hidden laws, by unspoken but profound assumptions on the part of the people.” These assumptions shape thought and action, functioning as unseen guides.

But rather than seeing racial inequality as the disease of modern American life, Baldwin saw it as a symptom of something else: the existential anxiety haunting modernity. He was clear about his task: “It is up to the American writer to find out what these laws and assumptions are.” Baldwin’s concern, then, was not just about race. It was about the way societies grasp for certainty where there is none, the way they impose fixed meanings to avoid the uncertainty of freedom. His most unsettling realization was that freedom was never a possession, never a settled condition, but always unfinished—an open demand that placed us inescapably in relation to others.

If this was true, then every attempt to fix identity was an effort to escape this burden. And so, rather than confront this weight, societies construct barriers—racial myths, national identities, moral fictions—to protect themselves from the abyss of the self. This was Baldwin’s insight in Notes of a Native Son—a vision of society bound together by myth, fear, and evasion.

Society is held together by our need; we bind it together with legend, myth, coercion, fearing that without it we will be hurled into that void, within which, like the earth before the Word was spoken, the foundations of society are hidden. From this void—ourselves—it is the function of society to protect us; but it is only this void, our unknown selves, demanding, forever, a new act of creation, which can save us—‘from the evil that is in the world.’ With the same motion, at the same time, it is this toward which we endlessly struggle and from which, endlessly, we struggle to escape.

Baldwin’s language is striking here. The void he describes is not external—it is within us. It is the part of ourselves we spend a lifetime refusing to face. We all have felt it—the ongoing pursuit to have one’s identity, relationship, job, nation make one feel truly at home in the world. It is freedom’s beauty and tragedy—the power to create the world we inhabit, and the demand that we bear witness to the inadequacies of our creations to settle our longing for security.

If Baldwin was a defender of liberalism, it was a liberalism haunted by its contradictions. His was an ethic of restlessness, a vision of freedom that refused sovereignty, bound not to control but to the fragile and terrifying work of being responsible for one another.

The United States, he thought, must forever hold two ideas which otherwise seem in opposition. “The first idea was acceptance, the acceptance, totally without rancor, of life as it is, and men as they are in the light of this idea, it goes without saying that injustice is a commonplace.” He was not naïve about the cruelty of power; he could be a realist about the persistence of racism. “But this did not mean that one could be complacent, for the second idea was of equal power: that one must never, in one’s own life, accept these injustices as commonplace but must fight them with all one’s strength.”

Baldwin understood that our myths are seductive. They allow Americans to imagine the past as settled, as though racial history was an unfortunate and anomalous chapter rather than an ongoing struggle. They sustain the illusion that democracy is self-perpetuating rather than fragile. Our myths invite the thought that history is creative and redemptive.

These myths also offer a reassuring but dangerous fiction: that freedom is about mastery rather than vulnerability, about dominance rather than interdependence.

But Baldwin understood that this was an illusion. Avoiding the past is one thing; denying its consequences over time is another. No work of his made this point more powerfully than The Fire Next Time from 1963. Black people needed to resist the entrapment of American life—the temptation to allow whiteness to define the terms of their anger. This was his critique of the Nation of Islam: as Baldwin saw it, the Nation of Islam merely reversed white America’s racial myths rather than dismantling them.

He understood, however, where power resided in American life, and so he reserved his most thorough criticism for white America. White individuals, he insisted, needed to forsake whiteness. We all must relinquish the ways our identities hinder our flourishing during this brief journey through life:

Perhaps the whole root of our trouble, the human trouble, is that we will sacrifice all the beauty of our lives, will imprison ourselves in totems, taboos, crosses, blood sacrifices, steeples, mosques, races, armies, flags, nations, in order to deny the fact of death, which is the only fact we have. It seems to me that one ought to rejoice in the fact of death– ought to decide, indeed, to earn one’s death by confronting with passion the conundrum of life. One is responsible to life: It is the small beacon in that terrifying darkness from which we come and to which we shall return. One must negotiate this passage as nobly as possible, for the sake of those who are coming after us.

We should all sit with this passage and let it swirl around our minds as we work through each word. The myths Baldwin describes still shape us—whether in the demand for sanitized history (e.g. “Make America Great Again”), in the resurgence of nationalist identity, or in the moral evasions that allow institutions to pretend that history has no hold on the present. These myths still function as shields against the truth that democracy requires both memory and struggle if it seeks to be responsive to the citizenry.

Rather than focusing on myths that divide and separate us, Baldwin thought we should commit ourselves to something nobler: how to live more humanely in relation to others now and through what we leave to the future. Our identities—all of them—are only as good as they put us in touch with others. If they obstruct our ability to see the humanity in others, we should be prepared to let them die off. A healthy liberal democracy, then, teaches us how to be free. But being free means learning how to let portions of ourselves go, as we grow in our humanity.

I know, and Baldwin knew this is hard. His realism was never too far behind. Myths, once constructed, have a way of hanging on; they become the albatross around our necks. They become almost impossible to abandon. A nation that clings to symbols of its own virtue buries the truth beneath rituals of denial. Those rituals show themselves in real time.

By the time Baldwin published No Name in the Street in 1972, the Civil Rights Movement had changed. Yes, there were victories—landmark legislation and expanded political rights—but the losses were profound. Medgar Evers, Malcolm X, and Martin Luther King Jr. were dead.

King’s death, perhaps above all else, cut to Baldwin’s soul. “I did not want to weep for Martin, tears seemed futile. I may also have been afraid, and I could not have been the only one, that if I began to weep I would not be able to stop.” King represented, for Baldwin, the power of moral uprightness in the face of white supremacy and the radical insistence that America live up to its democratic promise. His commitment to nonviolence was not just a tactic but an ethic—a refusal to surrender to the logic of domination, even as he exposed its cruelty. And King held his vision together in his legal-institutional appeal and call to transform the heart. As he put it in 1966: “our goal is to create a beloved community and this will require a qualitative change in our souls as well as a quantitative change in our lives.” In King, Baldwin saw America’s future and in his murder, he saw America’s betrayal.

The ideas that shaped Baldwin’s earlier works remained, but the tone shifted. If Notes of a Native Son had begun with betrayal and ended in the human desire to imagine society otherwise, No Name in the Street reversed the order. Baldwin still believed in human possibility, but he had seen too much to ignore the cruelty of American life.

Most people are not, in action, worth very much; and yet, every human being is an unprecedented miracle. One tries to treat them as the miracles they are, while trying to protect oneself against the disasters they’ve become.

Yes people are miracles and in that lies possibility, but disaster is likely to follow. “Perhaps,” he mused, “one can no longer live if one allows hope to die. But it is also hard to see what one sees. One sees that most human beings are wretched, and, in one way or another, become wicked because they are so wretched.”

As in Notes of a Native Son, the issue was how to be clear-eyed about our wretchedness while still fighting for our transformation. Can we accept the first while remaining passionately committed to the second as our moment requires?

Baldwin’s work does not give us an easy answer. He does not offer a path forward, a policy fix, or a simple moral. He does something harder: He forces us to confront what we are. He asks us to consider whether we are willing to bear the weight of freedom or retreat into illusions that demand nothing of us.

This is why Baldwin remains so unsettling. He understood something that few are willing to admit: the past is never truly past, and the choice to evade it is always present.

And here we are again, confronted with a choice at a time that feels far more momentous and darker. The United States faces another reckoning with itself. Illiberal politics is here, but the voice of liberalism is now actively suppressed. History is being policed, free speech is under attack, and resistance itself is being criminalized. All this signals a similar crisis Baldwin diagnosed, but qualitatively worse. For in Baldwin’s time there was the attempt, even if deformed, to speak in the name of liberalism. Today, the highest office in the land expresses open disdain for liberalism and the power of the people.

Are we willing to bear the weight of freedom and confront the unknowable darkness this moment presents? Or will we once again retreat into myths that offer a false sense of security at the expense of justice?

What Baldwin leaves us with is not an answer, but an unrelenting question: Are we willing to bear it?

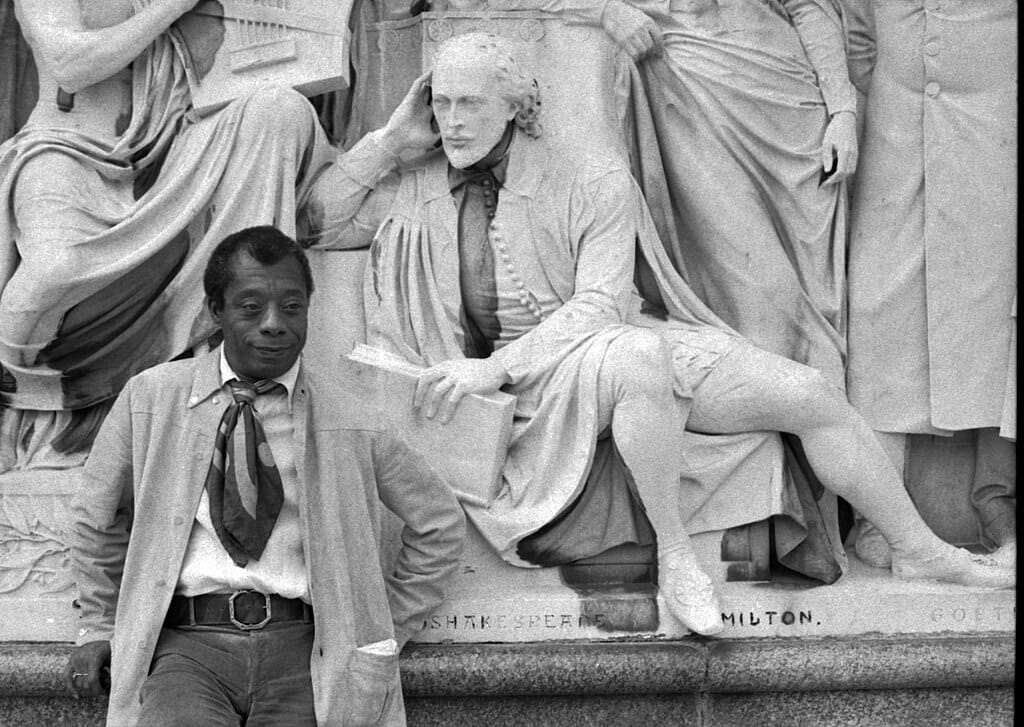

Featured image is James Baldwin on the Albert Memorial with statue of Shakespeare, by Allan Warren