Bluesky Won't Save Us

Like radiation, social media is invisible scientific effluence that leaves us both more knowledgeable and more ignorant of the causes of our own afflictions than ever

If you take nothing else from this essay, understand this: you should quit Twitter. Yesterday.

Contra the opinions of Twitter addicts desperately clinging to fantasies of engagement for ever-diminishing dopamine hits, Twitter is, as predicted, nothing like what it used to be and very, very far from whatever it could have been without the depredations of Elon Musk’s ideological perversion of the site’s very code.

As many have recently observed, the notionally-decentralised Bluesky has rapidly emerged as the microblogging platform for people looking to get eyeballs on their work—from journalism, to fine editorials like the one you’re now reading, to Etsy shops, to fanart pages, to Patreons, the clickthrough conversion rate is eyewatering (at least, in comparison to the current iteration of Twitter; take that relativism for what you will).

Twitter is failing as a news-dissemination platform. It is failing as a platform for helping freelancers get seen and get work. It is failing as a place fit for children and other living things. It is the personal fiefdom of a mercurially maniacal billionaire who seeks to destroy democracy itself in order to explore the final frontiers of being divorced. To be there is to merely add your cellular mass to its tumour. There is no activist, business, or personal reason that could possibly keep you there now.

So. Now that Alexandra Ocasio-Cortez, Flava Flav, and Black Twitter (now BlackSky) are on Bluesky, is all well? Surely you should join them. Leap up into the Sky; the air is fine.

Well, sort of. You should calibrate your expectations. And, frankly, so should Bluesky’s founders. You see, the massive influx that saw tens of millions of new users flood into Bluesky over just the past month also—to use a delectably Marxist term—sharpened the contradictions of the platform.

Largely because Bluesky is a platform that resolutely wishes it wasn’t. And that has profound implications for what its users want the platform to be, and what it can’t; in short, why it will not save us.

If you know anything about Bluesky beyond the surface level of “it’s like Twitter but not owned by Elon Musk, and therefore not overrun by Nazis and painfully unfunny people who paid 8 dollars a month in order to pretend their posts are interesting,” you’ve likely heard of the AT Protocol. This, in truth, is the point of Bluesky.

In many ways, it’s helpful to think of the Bluesky you know as a kind of elaborate tech demo for the AT Protocol, which is essentially a set of rules that governs the creation of a microblogging system—though it can be used for other applications as well. It’s a way of creating something you own with Bluesky’s bones—potentially like having your own website.

When you listen to Bluesky CEO Jay Graber excitedly talk about her protocol’s potential, she likes to say it’s “billionaire proof,” arguing that what happened to us erstwhile Twitter users can never happen to Bluesky, even if she sells out and lets some crypto billionaire buy the place. Why? Because you own your account, your posts, your network, the lot. You can do anything you like with it, moving it to a different piece of the protocol, some other instance of Bluesky that was never owned by the Bluesky company, but perhaps by you, or a friend, or someone you like or follow, and which can be federated with any other instance of Bluesky.

In this way, Bluesky is like a more accessible version of Mastodon: a necklace of servers, all independently owned and operated according to their own rules and with their own esoteric little tweaks to the source code that allow for bespoke mini-platforms—which can talk to each other, or not, depending on who’s running your little bit of the AT Protocol.

This is at the heart of Bluesky’s decentralised, anarchistic ethos. There are no hierarchies, there will be no total ownership. Instead, the users are in control, and it is their popular will that will decide everything: which of the user-directed “composable moderation” tools becomes most popular, which instances become the most influential and which become the most blocked, and even the ultimate shape of the protocol itself. Power to the posters.

The Bluesky you likely use if you’re reading this is the bsky.social instance, which, for all intents and purposes, is a Twitter-like platform. It’s where most of Bluesky’s vaunted 20 million-plus population skeets their days away. This is the heart of the tech demo, showing what the affordances of the AT Protocol allow you to do, from familiarly Twitterian functions like sharing or commenting, to the more overtly Blueskyish moderation functions that allow you to subscribe to lists and mute or hide posts or users with specific, user-generated tags on them.

But here’s the thing: it seems like most new users are content to stay on bsky.social. And they want Bluesky Social PBC to run it like a platform for which they’re responsible. There’s also a degree to which, so far as the average user is concerned, Bluesky’s decentralisation is greatly exaggerated—its very architecture means that while you notionally own your account and data, and can transport it across the protocol, unless you own your own personal data server as well, all of that is hosted on Bluesky Social PBC property.

Meanwhile, their relay server is what will hoover up info from the PDS and present it to you through the AppView (what you might think of as Bluesky’s API); all of that is owned by the company, and it needs to be as there a lot of functions that only the company can ever hope to perform at scale. As the technologist and co-author of ActivityPub Christine Lemmer-Webber puts it:

"There will always have to be a large corporation at the heart of Bluesky/ATProto, and the network will have to rely on that corporation to do the work of abuse mitigation, particularly in terms of illegal content and spam. This may be a good enough solution for Bluesky's purposes, but on the economics alone it's going to be a centralized system that relies on trusting centralized authorities." (Emphasis mine).

This, at last, brings us back to the contradictory expectations of Bluesky corporate and Bluesky’s users.

The problem with ‘Power to the Users’ as an ethos is that there are simply some things that users can’t do. Foremost among them is content moderation at the scale of millions of users.

As I predicted last year, leaning on community moderators and labellers on Bluesky was unsustainable; controversies and personal drama have already seen some of the earliest successes on the platform go down in flames. After all, how do you decide to trust a random user’s mod tools? And if a labeller has to have anonymous mods to protect them from harassment and pressure campaigns, how are they to be held accountable if something goes wrong? None of the tools available on a microblogging platform insulate any of these people from the terrible network effects of mobbing and drama-mongering—consider all the theatrics that surrounded the false-positives of the technologist Randi Harper’s GamerGate blocklist years ago on Twitter, then add to that a reduced barrier to entry for Bluesky, and you get some sense of the problem’s scale.

And it’s no coincidence that some of the worst battles faced by Bluesky corporate have stemmed from their desire to keep their hands off direct moderation—which Graber has, in the past, likened to “resolving all disputes at the level of the Supreme Court.” This is not strictly wrong, of course. There’s a real degree to which the users of a community should be empowered to take responsibility for the space and do their part. But, inescapably, platforms have to moderate—scholars like Tarleton Gillespie have gone so far as to argue moderation is an essential characteristic of platforms, after all.

Two controversies illustrate this plainly. The first is from the summer of 2023, when it became clear that Bluesky—which was still invite-only at the time—had no means of automatically filtering out usernames with slurs. Black Bluesky users drew attention to an account that literally had the n-word in its username, touching off a firestorm of criticism that caused the company to take a stronger and more proactive stand on controlling the platform.

The second controversy is ongoing. The blogger Jesse Singal, who is now best known as a provocateur and an activist against gender affirming care for transgender children, joined the platform. Discussing him in any critical way tends to court a firestorm from him and his fans, so it is enough to say that many others have written at length about the issues in his work. Many users—especially the site’s more prominent trans users—are arguing it’s a no-brainer for him to be permabanned from the platform. As of this writing, Bluesky finally addressed the matter with a thread from their Safety account, suggesting that Singal being temporarily banned twice was due to an error in Bluesky’s automated impersonation-detection systems, and that the company was not keen to moderate its users on the basis of anything they did off the platform. They conclude by reaffirming the source of the contradiction I’ve been describing here:

“Moderation decisions draw intense public scrutiny from many places. That’s why Bluesky's architecture is designed to enable communities to control their online spaces, independent of the company or its leadership.”

In short, you have the tools to moderate your own experience, use them, and stop haranguing us. In the immortal words of Fallout 4, everyone disliked that.

These moderation farragos illustrate that users want Bluesky to act like a platform and set a firm floor on what and whom will be allowed on bsky.social, not merely leave it to the currents of composable moderation and the whims of individuals. We can, yes, curate our own feeds. But, many users argue, we should treat this place like a platform and say some things/people should never be allowed— even if only as a statement of principle.

And curating feeds is work. It’s why volunteer moderators are praised as heroes (at least, before the inevitable drama shitstorm). As much as people like me complain about the deleterious effects of centralisation, the walled gardens are attractive because they offer people everything they need. Software that just works—much like the value proposition of, say, Apple OS as opposed to Linux.

So where do we go from here?

The Singal controversy matters in part because it touches on a larger issue with these sorts of social media platforms more generally. They have been radicalisation pipelines par excellence, in no small measure because credulous journalists and academics, who are too addicted to the platforms, get used to launder extremist ideas into the mainstream. Your average New York Times subscriber is not Extremely Online but is increasingly being fed opinions and ‘analysis’ from writers who are, and who find themselves increasingly angry at all the annoying people who spoonerise their names and troll them on platforms.

Trans people are a good example of this. Some small group of angry trans people harangues a journalist—rightly or wrongly—for being a bigot, and then this feeds a resentment that others like Jonathan Chait or Matt Yglesias give shape and form with plausible, lib-pleasing moderate language that, in turn, those Extremely Online journalists transcribe into the pages of respectable publications.

There are few ways of explaining the obsessiveness with which the mainstream press has published stories “critical” or “skeptical” of trans people without recourse to social media and how it makes us loom large in the minds of the terminally online, nor how that overemphasis has been adroitly exploited by provocateurs who’ve long dripped poison in the ears of epistemic movers and shakers. It’s not unreasonable to suspect that Twitter played a leading role in radicalising J.K. Rowling or Elon Musk against trans rights, for instance.

So, if Bluesky remains a centralised platform, banning bad actors like Singal is one way to try and break the pipeline. But not completely. After all, before Musk’s takeover, Twitter had been banning some high-profile bad actors. It wasn’t enough. The scale of the platform was too massive. If Bluesky keeps growing, it too will microwave the brains of too many influential people, with consequences unpredictable in every way—save for the fact that they’ll not be terribly good for pluralism and democracy.

If Bluesky corporate’s dream of a decentralised protocol comes true, meanwhile, we might blunt some of the impact of this, breaking up the userbase and putting up walls and hurdles between different parts of the protocol until it resembles something more like Mastodon, or even just the Web itself. But then, that, of course, produces the risk of ATProto versions of Stormfront or Gab that no one can do anything about. Isolated hubs, yes, severed from much of the rest of the protocol, but still there and still radicalising people into committing harmful acts. After all, even KiwiFarms, the infamous stalking and harassment forum, was chased off most of the clearweb, but it still exists and still foments hatred.

We can hope that decentralisation is enough to forever cauterise the wound of disinformation and radicalisation, but it may just present us with a different flavour of the problem we already face. And that’s assuming we even get there. With each passing day I feel doubtful Bluesky will ever be able to be much more than a very effective Twitter clone. After all, that’s what most people seem to want it to be. While there are many private PDS owners, and many intrepid techies doing fun things with the protocol on their spare time, the modal use case appears, for now, to be using Bluesky’s bsky.social as a full-on Twitter replacement, where we are all doused by the same firehose at full blast.

Our best hope, then, is that Bluesky acts as a halfway house—most especially for politicians, journalists, academics, influencers, and other people who clearly spend way too much time online to their detriment. After all, it’s becoming clear that noted coup aficionado Yoon Suk Yeol was increasingly radicalised by watching too many right-wing YouTubers—some of whom he’s brought into his own government—to the point of becoming a conspiracy theorist who nearly torpedoed his own democracy.

Beyond that, Extremely Online journalists end up mistaking viral trends for the pulse of the nation—see last year’s fiasco about how TikTok teens were, supposedly, cheering on Osama bin Laden’s manifestos (which turned out to be based on a mere handful of TikToks). Or consider the burbling moral panic that’s cropped up about Luigi Mangione’s supposed popularity (polls tell a different story).

In each case, however, the controversies became all the more viral because of the undue attention heaped upon them by people with far larger platforms. One wonders if all the anxiety occasioned by the “is Bluesky a left-wing echo chamber?” pieces led Bluesky corporate to treat certain malefactors with kid gloves. Which makes the site more toxic and creates yet more sludge that gets slurped up into the mainstream press and institutions. In this way, excessive dependence on social media platforms creates an ugly feedback loop that can swallow our dreams whole.

Worse, however, is how the entire recent drama about moderation has driven some trans Bluesky users into the deepest pits of despair, which they then feed through doomscrolling their feeds. The exact truth of how Bluesky has handled what technologist Faine Greenwood calls L’Affaire Singal may not be known or knowable for months—but rumours have heaped upon rumours played through the vicious game of telephone only social media networks can proliferate at such speed, causing shadows to dance upon the minds of people already depressed by the larger political situation.

There was some hope—hope I may have played a role in spreading—that Bluesky was capable of being something different from what had gone before. That if it remained a centralised social media platform it could, in fact, be a good one. But, like a flash of lightning on a dark night, this latest moderation fiasco, with its thunderous echoes of the n-word saga from last year, has reminded people that platforms will always struggle to moderate, and, at a certain scale, will never be free of controversy or prejudice or bad faith manipulation attempts. It’s clear that Bluesky can do more—but the company’s desire to proliferate a protocol rather than administer than a centralised platform will always get in the way. And in this moment of profound despair and hopelessness about the future, it may be wrong to place our hopes in any kind of centralised platform to begin with. These are not the commanding heights of culture but perpetual motion machines of despair whose administration frequently serves to produce still more of the same.

If we are to develop resilience for the coming years, we will have to log off at least some of the time. Indeed, I’d go so far as to say that social media in its current form is so harmful as to merit a blanket ban—amidst all of the foolish piddling about age restrictions on social media, amidst the panic over Chinese control over zoomer-beloved TikTok, we are neglecting the fact that the middle-aged and elderly are the ones whose social media addictions have truly wrought havoc on our democracies, after all. Why not treat social media like pollution, smoking, or (the way we used to treat) gambling? Like radiation, social media’s algorithms and network effects are invisible scientific effluence that leaves us both more knowledgeable and more ignorant of the causes of our own afflictions than ever; in turn, this leads to deepening distrust in the experts who are blamed for producing them—in the precise manner that scholars like Ulrich Beck warned about. Cue the doom spiral we’ve all been living in.

But I also think, perhaps more moderately, that Ian Bogost is right: whether we like it or not, we are looking at a twilight of social media hegemony. The model is simply burning itself out. Bogost himself regards Bluesky’s newfound popularity as a relapse more than a renaissance; I agree. If Bluesky does any good, it’ll be as a sort of methadone for Twitter. Put simply: staring at the doomscroll isn’t good for anyone, but it’s especially dangerous for people with power and influence. Perhaps such a harm-reduction approach is more compassionate than an outright ban, weaning overly online journalists and celebrities off of the more dangerous stuff, steadily unplugging them from the Necronomicon of networks no mortal was meant to stare into.

And eventually, those people who needed it all so much will simply log off more often. For longer.

We might all know some peace then.

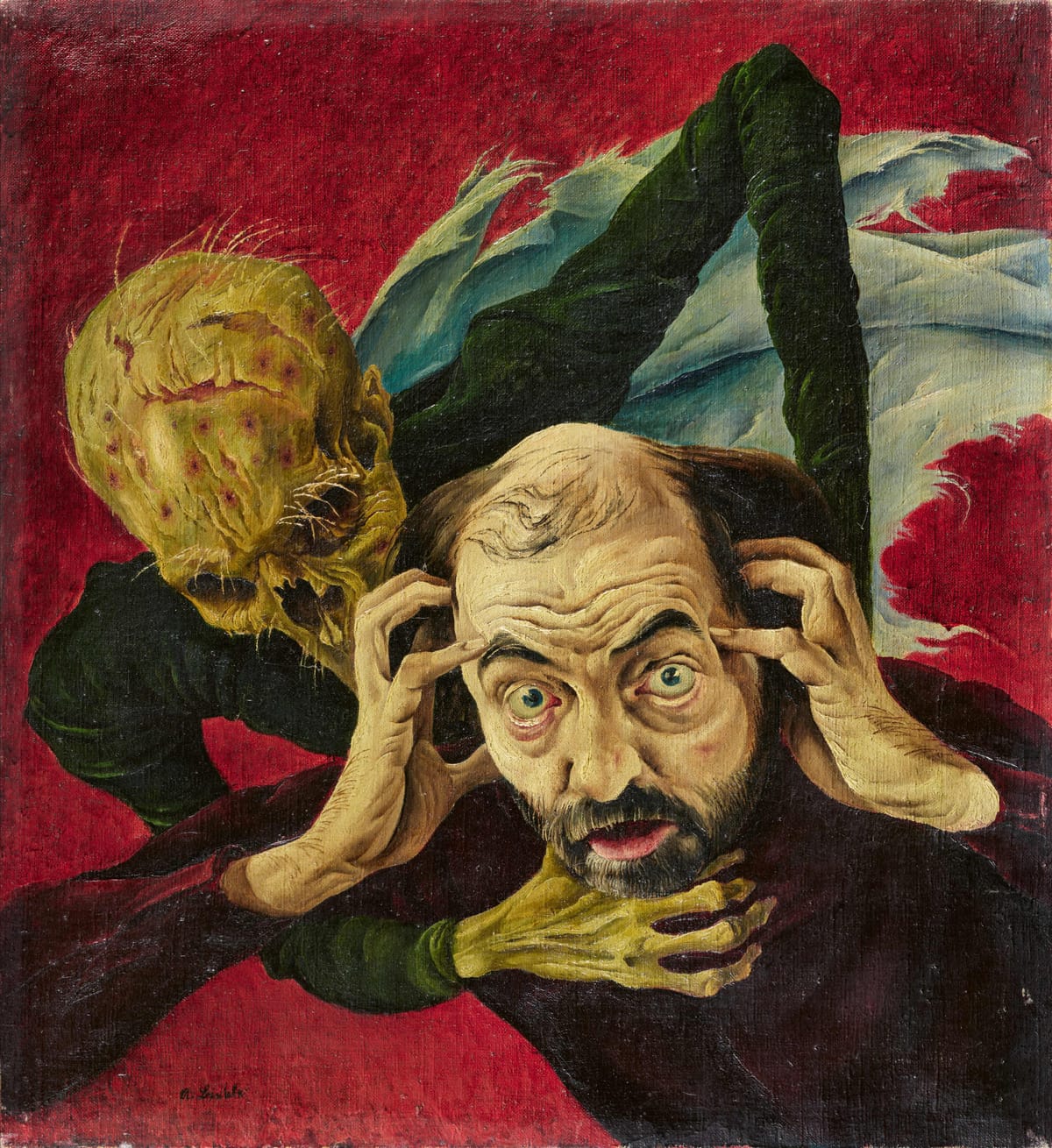

Featured image is Lot 29, by Albert Birkle