Big Structural Change—Jesus to Marx

Only in modernity can the rich tell themselves that it is wrong to pity the poor, that their own wealth alongside another’s poverty is simply justice in action.

There remains a culture of popular adoration and mystification around the extremely wealthy, but objection to the very existence of billionaires is now widespread. Such objections run the discursive range from anonymous internet users posting choppy-choppy guillotine memes to serious economic and historical works from scholars such as Thomas Piketty. According to one postmortem on the 2024 US presidential election, it is now simply obvious that “an engorged, predatory, and increasingly insane billionaire class, obsessed with eugenics and immortality” is among the major features of the US political landscape in the early 21st century. That money is power, that vast sums of money corrupt democratic elections in a variety of ways, that the laws that bind most people do not apply to billionaires, that in consequence extreme wealth generates a range of character defects, not to say actual moral monstrosity—these are fairly mainstream ideas, qualifying even as common sense.

These, or analogous positions, have always been central to the western tradition of political thought—so, at least, is the major claim of David Lay Williams in The Greatest of All Plagues. The organizing term of the book is pleonexia, a Greek word that translates as greed or avarice, signifying insatiable, infinite possessive desire (29-30). Each of the book’s seven chapters takes up a different canonical figure: Plato, Jesus, Hobbes, Rousseau, Smith, Mill, and Marx. Williams has chosen canonized authors because he wishes to demonstrate that, pace readers like “Steven Pinker, Tyler Cowen, and David Brooks” (5) or even Milton Friedman and Friedrich Hayek, these major figures argue “with striking consensus that excessive inequality threatens to divide communities, pit citizens against one another, undermine democratic legitimacy, and, in the most extreme cases, even foment revolution” (5). Concerns with and responses to wealth inequality, Williams writes, “are not ancillary to the Western tradition—they represent much of that tradition’s core.” (17)

The center of the book literally and conceptually is Rousseau, who was also the subject of Williams’s first monograph. Plato, Jesus, and Hobbes Williams examines with Rousseau’s own readings of them in mind. Smith, Mill, and Marx either neglect or pick up and develop in new directions Rousseau’s innovations. Although several important lines of argument emerge only from the whole of the book, each chapter stands on its own and could be read with profit by anyone interested in these thinkers. Most striking, looking at the whole, is not that the problem of economic inequality is so widely recognized, as that there have been so few plausible solutions offered to it.

In the first chapter Williams argues that alongside Plato’s famous elitism there is a clear, but usually in the scholarship underplayed, recognition of the destructive, corrupting nature of disparities of wealth. Plato appealed to the law codes of Solon and Lycurgus to warn his readers of the threat of “violent class based revolution” (21) that inequality poses.. In the Laws, the figure of the Stranger explains that justice means that laws “are laid down for the sake of what is common to the whole city” (35). Justice, this is to say, is “general rather than particular” (36)—here Plato anticipates Rousseau’s general will. Significant inequality of wealth necessarily generates laws that are partial—the wealthy use the power their wealth brings to make laws to their own benefit. The Stranger “detests both concentrated wealth and inequality as the origins of nothing less than “the greatest of all plagues” (Laws, 744d), which is social disharmony and civil war” (37).

In the thought experiment of a new society, founded from a position of total equality, we get a more concrete set of proposals. Each individual should have enough land to live without poverty, but no one should be allowed to accumulate more than about four times this much wealth (42). Plato’s Stranger mentions mechanisms for preventing excessive accumulation that include limits on inheritance, and marriages, as well as a ban on interest-bearing loans, on buying or selling land, even on the accumulation of precious metals (43-4). Williams is quick to say that Plato was no revolutionary, that abrupt change is destructive even if the end is a good one, and so that while some societies are too far gone into inequality for it, incremental reform toward equality should be the order of the day where possible.

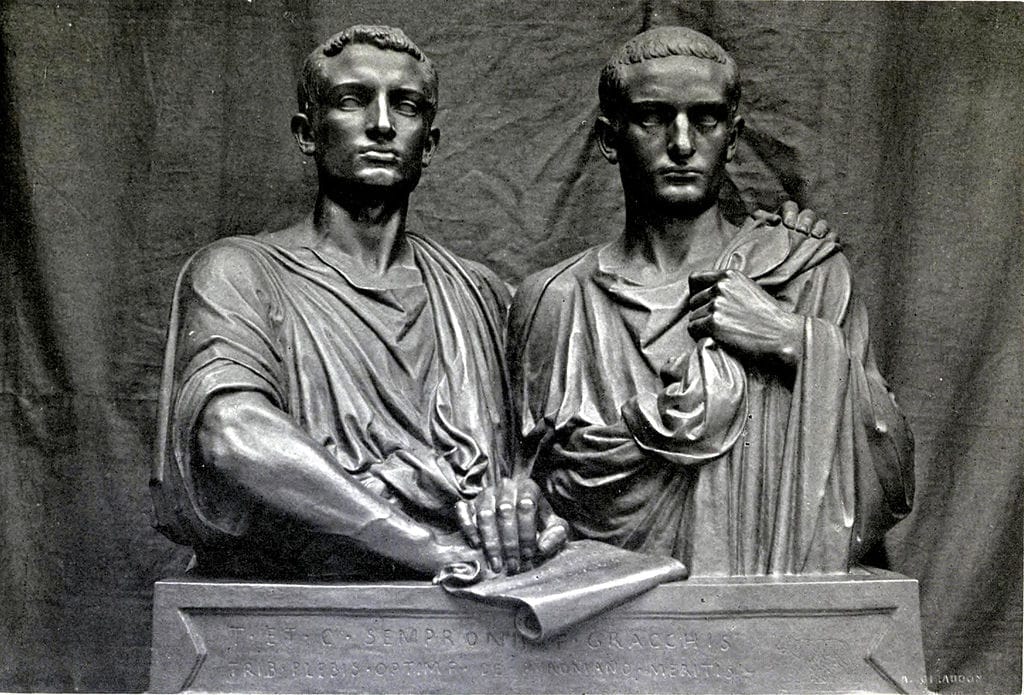

Williams acknowledges that Plato’s egalitarianism extended only to citizens, and left slaves and women out, although he argues that much of Plato’s program is independent of these restrictions (51). And, too, it is important for Williams that Plato, of all the figures included in the book, is the one born into the most illustrious family. Critics of wealth really can come from the wealthy classes (54). This is significant because one aim that seems to run through this book is to speak to the very wealthy themselves, to argue for the moral reform, as it were, of the wealthy. Plato, from a family claiming descent from a god, stands at the beginning of Williams’ tradition of anti-plutocratic theorizing.

Many of these themes return in later chapters. Each chapter begins with context, defined both materially and discursively, and then passes to a consideration of the major works of the author in question. The aim in every chapter is to “sketch the ambitions or highest goals of its respective thinkers” (67) and to argue that a critique of inequality is integral in every case. The chapter on Plato is followed by one on Jesus. Williams wishes not only to contextualize Jesus in historical Roman Palestine, and to make the (fairly straightforward) case that Jesus actively disparages wealth, but also to argue that the older Jewish laws about Sabbatical and Jubilee—regularly scheduled and divinely ordained debt forgiveness and property redistribution—are more literally adopted by Jesus than is typically admitted. The next chapter, on Hobbes, intends to show that for this figure so often made to stand at the very beginning of political modernity, inequality of wealth weakens the sovereign so that it becomes “fundamentally political, demanding political interventions” (134).

Rousseau, however, is the pivot of the book. Williams argues convincingly that a critique of economic inequality is fundamental to Rousseau’s “most significant constructive political concept—the general will” (137). Yet of all the figures in this book Rousseau seems the most deeply confused about the nature of the economic transformations surrounding him. It is not just that he dissented from the 18th century’s enthusiasm for the civilizing effects of commerce. Williams writes that “wealth is, for Rousseau, a zero-sum game. For one person to acquire massively superior wealth, others must surrender it” (144). Plato thought the same thing, but it ought to have been clear to Rousseau that by the middle of the 18th century this was no longer the case—as it was clear, for instance, to Mandeville.

At the same time, Rousseau was enormously foresighted in offering a critique of meritocracy as an excuse, a justification, for economic inequality. He was a keen critic of modernity as it was emerging, which for Williams (and many others) is marked by “the degree to which Europeans were freed from ascriptive status” (157). If one’s grandparents’ titles could no longer justify one’s yearly income, what could? Meritocracy. For Williams, the “analysis of the underlying moral psychology of inequality of meritocratic societies is one of Rousseau’s most novel and greatest insights” (157). Only in modernity can the rich tell themselves that it is wrong to pity the poor, that their own wealth alongside another’s poverty is simply justice in action.

Rousseau’s contemporary Smith was much more attuned to the commercial society emerging from feudalism—as Williams repeatedly calls it—and while he did worry about excessive inequality, he could not bring himself to offer any positive program against it. Smith had a much stronger sense of the benefits to society at large of the emulation and striving to which inequality gave rise. He also believed that the market itself could correct what was most bad in it (188). For the poor, aside from economic growth, he counseled mainly education, moral and practical, but also the vigorous and consistent application of law (192-93). Smith’s awareness of the dangers of enormous fortunes for both political and moral life is never really matched to systematic solutions. He in any case found “the dangers of poverty…still more alarming” (199) than those of excessive wealth. Smith comes closest of any of the figures in the book to defending the “sufficientarian” position against which Williams frames his argument, but even he is radically more concerned with the moral corruptions attendant on massive accumulations of wealth than are many modern writers.

The final two chapters deal with two figures who, like Smith, put political economy at the center of their worldview, finding the development and accumulation of material wealth to be among the most important features of the modern world. Near contemporaries, John Stuart Mill and Karl Marx nonetheless had rather different ideas about the significance of inequality. Mill wrote among the most widely read textbooks of political economy of the 19th century, and stands metonymically for liberalism (perhaps excessively so). He tended later in his life toward socialism, and Williams reads him with real sympathy. Mill emerges here very much as the ideologue of the middle classes. Extreme poverty is bad, to be sure, because it is incompatible with moral life altogether. The genuinely impoverished are the natural enemies of society, for Mill as for Hobbes, and if the law must nonetheless continue to punish them they can hardly be blamed for attacking a world in which they have no stake. The very rich, born into idleness, are equally immoral, or rather amoral, “spoiled children” who for different reasons than the poor are unable to control their impulses. Williams quotes Mill: “inequalities of wealth…have as pernicious an effect on those whom they seem to benefit, as upon those on whom they apparently press hardest” (217)—there is the quintessence of a certain kind of liberal moralizing.

Yet Williams also presents a more interesting Mill, drawing in part on Helen McCabe’s work to emphasize the theme of fraternity. Perhaps not explicitly referring to Plato, Rousseau, and Smith, but “certainly resembl[ing] them,” is a Mill for whom “economic inequality undermines the kind of moral community that characterizes healthy societies” (220). Mill recognizes very clearly that “money is power, and the most efficient way to exercise that power is to…shape legislation” (221). It is thus in the realm also of legislation that democratic equality can best combat plutocracy. Despite Mill’s famous flexibility regarding suffrage—the very poor ought not vote, and the well-educated should have more votes—he did, with Tocqueville and many others, see a link between political democracy and economic equality. The legislation and social programs he envisioned are not all equally compelling in the 21st century. Certainly his enthusiasm for the moral education of the poor has a paternalistic ring to it (the poor are poor in part because they can’t stop having babies). He is certainly the only figure in the book to have been arrested for distributing information about birth control (239)!

Running throughout the chapter on Mill—as throughout Mill’s body of work—is the classic conundrum of “radical” political economy: people are free to choose to organize society differently than it is organized at present, but also they must be coerced, pushed, into doing so. For this reason, education plays a key role for Mill. That is where moral autonomy can be fostered, where an ethos of public-spiritedness can be taught. Mill understands of course that other institutions must change—estate taxes, for instance, to undermine the generational accumulation of wealth—but nonetheless for him education is key, partly because one can insist on the conditions for it, among them a reduction of extreme poverty.

Perhaps most remarkable is Mill’s formulation of “the stationary state,” which is a thought experiment or extrapolation about a post-growth world. The idea comes in response to the Smithian imaginary of eternal growth, but also out of Mill’s belief that, ultimately, the point of being human is self-development beyond mere material gain. For Mill, “the energies of mankind should be kept in employment by the struggle for riches, as they were formerly by the struggle of war, until the better minds succeed in educating the others into better things”—but those better things are indeed the goal (251).

There is a Malthusian element here and, as Williams emphasizes, an environmental one. Mill imagines a world totally covered over with either dense cities or industrial-scale agriculture, and is disgusted. For Mill, there is a sharp difference between backward and advanced economies, as there is between the barbarous and the civilized. The former are caught in material and historical necessity, the latter have a chance at self-direction. In advanced economies “distribution” remains in the hands of human institutions and therefore human decision-making. In the stationary state, society would be so organized as to interrupt pleonexia, both at the social and the individual level. Education and other social pressures would discourage if not eliminate competition over material wealth, but also law would mean that a person could never inherit or be given more than a certain amount of money, “the amount sufficient to constitute a moderate independence” (252). This is by no means a classless society, but Mill imagines that the working class will be “well-paid and affluent,” that there will be “no enormous fortunes,” and that many more people than at present can live without toil over “mechanical details, to cultivate freely the graces of life” (253). Here we find again Plato’s vision of a world in which, material needs met and limited socially, the virtues may be practiced. It is, we are tempted to say, the paradise of social democracy.

Williams’s final chapter integrates Marx into his story of pleonexia and political theory. His is a republican Marx, and the chapter engages explicitly with William Clare Roberts’s Marx’s Inferno. As with Jesus and Rousseau, few will be surprised to hear that Marx was opposed to extreme disparities of wealth. Any casual reader of Marx knows he is capable of extraordinary venom regarding the many moral failures of bourgeois society. A slightly more than casual reader understands that for Marx the inequality inherent to capitalism, pushing society into two ever more sharply divided classes, does not depend on any one particular person’s greed. Marx wrote both as a polemicist about individual moral failures and as a scientist describing the dynamic of capital at a level no more dependent on individual ethical lives than is the process of evolution.

Williams is right to insist on the moral dimension of Marx’s work, and the suggestion that Marx’s analysis of capital as a social process fits into the history of pleonexia Williams has been writing is an interesting one. It does sometimes feel that he is trying to have his cake and eat it too. For Marx, “bourgeois pleonexia is the animating force of capitalism” (284), but so too is capitalism a social system in which pleonexia appears simply as rational behavior—Williams quotes Marx: “what appears in the miser as the mania of an individual is in the capitalist the effect of a social mechanism in which he is merely a cog” (290). Plato, too, had spoken of pleonexia as a compulsion, a form of unfreedom on the part of the one driven to accumulate, who becomes a slave—what really does that compulsion have to do with the “cog” that the capitalist must be? With Mill we get a contradiction of sorts between social structure and individual moral capacity, but this is just the kind of problem that Marx sees as wrongly posed.

It is not so much that Marx’s originality—pace Williams—lies in seeing class antagonism as the solution to excessive wealth accumulation. Put in that way we might look back perfectly well to Machiavelli. Rather, for Marx, revolutionary transformation will abolish the conditions of social compulsion that make pleonexia other than a personal moral failing. This is a more radical change even than the flood that Plato’s Stranger imagines as a beginning for an egalitarian society. For Mill, we as human beings can choose to transform our institutions into the stationary state. Can we, for Marx, make such a choice? Will that world not, rather, be thrust upon us by mutations in the means of production, heightening the contradictions of our legal order until it breaks apart and frees essentially social wealth from private appropriation? One might argue that Marx shows that "inequality" is an inadequate expression of what is happening here, that pleonexia in modernity at least has another proper name—capitalism. Political theory would then be subordinate to the analysis of the dynamic of capitalism and its effects—the hard limits it places on individual action, the shape it gives to political subjectivities, to any conceivable analysis of moral psychology, and so on.

Leaving aside the sufficiency of that Marxist response, let me end with a few observations. The first is that this book really is centrally concerned with the tradition of political theory as such. It is after all a book about economic inequality that resolutely avoids economics or economic history—nor is it a book about money as such, its peculiar ability both to free and to ensnare, its double nature as commodity and means of exchange, its ghostly life as a concrete abstraction. What emerges from The Greatest of All Plagues is that stark inequalities of wealth, just because they are also great inequalities of power, threaten political community as such—first through the legal order of the political society, fractured by the power of the rich to make their own law, and then through the psychologically and even epistemically distorting effects of this disparity. In every case, from Plato through Jesus and John Stuart Mill, the challenge has been to figure out how rules can be made to apply in any meaningful way to the poor and the rich alike—perhaps in the kingdom of heaven, perhaps in the stationary state. And this is a challenge that the figures in this book mostly do not meet. The anti-plutocratic techniques on offer in The Greatest of All Plagues are surprisingly thin.

Never in the past, as far as I know, has moral suasion, or a demonstration of the psychological damage attendant on massive wealth, had any significant capacity to limit its accumulation. It may be worth thinking about the pathologies and blinders attendant on wealth and power, and the history of such reflections is of scholarly interest. Yet in the 21st century this is thematized again and again in popular media. Ours remains a democratic world at least in that even the hyper-wealthy can and do make asses of themselves on the internet like everyone else. The moral psychology, or its failure, on which Williams spends significant time, is on display every day. The anti-plutocratic vernacular is widely spoken already.

What then is the role of political theory, specifically? The history of political ideas, or political theory pursued historically, may help us in the present by considering the concrete forms that anti-plutocratic power may take. Does one strengthen the Hobbesian sovereign? Or will the gnawing effects of market competition, properly established, do the trick? Perhaps a class-based political party aiming to conquer state power and use it to expropriate the expropriators? Perhaps there is a constitutional arrangement, one that might focus on a democratization of money itself? The solutions that Williams seems to favor all pass through the nation-state and its laws, but his book as a whole suggests that it is just the capacity of such a state to act that is thrown into question by extreme wealth.