An Exercise in Political Imagination: the Day Stephen Bright and Bryan Stevenson Debated William F. Buckley

Bright and Stevenson defended the abolition of capital punishment at a moment when political support for that movement reached its nadir.

As Americans contemplate whether and how to reverse War on Crime policies, it’s important to recognize that strategies of resistance were staked out decades ago. Moreover, the defense of liberal values and liberal institutions that proved most successful in this context had less of an abstract quality and more of a gritty, pragmatic character.

Those who lived through the 1990s saw not only record numbers of fellow citizens incarcerated—more than any other country in the world—but also a strong taste for harsh punishment—reflected in longer sentences and expanded use of the death penalty. Support for capital punishment actually dipped below 50% in the 1960s, but rocketed upward to 80% over the subsequent three decades as concerns about violent crime rose. Bipartisan support of aggressive anti-crime policies would soon lead Congress to enact the 1994 Crime Bill, a signature initiative of the Clinton administration, which expanded the death penalty, dangled grants for states to build more prisons, and popularized the “three strikes” approach to sentencing. Senator Joe Biden decried “predators on our streets” who are “beyond the pale” and must be taken “out of society.” Even then-Congressman Bernie Sanders, who warned that legislators were “dooming today tens of millions of young people to a future of bitterness, misery, hopelessness, drugs, crime, and violence” nevertheless voted in favor of the bill.

In courtrooms across the land, the fervor for swift, harsh justice led some prosecutors to cut corners and stack the deck in favor of the death penalty by artificially limiting the number of black people and women who served on juries. They would tell jurors to think of themselves as “soldiers” in the war on crime and describe black defendants using racially inflammatory terms. Judges facing reelection also gamed the system by appointing inexperienced and overmatched attorneys for people too poor to afford to hire their own. Through these and other techniques, an already unequal justice system became even more unequal.

The race to incarcerate made a new generation of advocates crucial to the survival of liberal institutions and values in the age of mass incarceration—including the ideal of adversary justice, racial equality, and the legitimacy of a democratic state, whose overriding goals are security and justice. After all, as the civil rights movement went mainstream, its leaders focused public attention on workplaces, restaurants, and hotels, and away from the criminal justice system. The problems with courtrooms and prisons always existed, but the failure of significant progress coupled with the ascendance of tough-on-crime public servants exacerbated those inequities and overwhelmed already burdened legal systems. Making headway against these ominous trend lines required not only that advocates take up the fight in states and counties where unequal and brutal justice was the most acute, but also that they discover new kinds of strategies and arguments.

Back in the Spring of 1994, Stephen Bright had just completed his first year of law teaching in New Haven. Bright, who was trained as a legal aid lawyer and public defender, had emerged as a fierce advocate for poor people on death row and leader of the Southern Center for Human Rights in Atlanta. He had been brought to the attention of Guido Calabresi, the Dean of Yale Law School, by former law clerks of Judge Skelly Wright. Skelly Wright’s family had affection for Yale because the university had given the judge an award for courage when his desegregation orders earned him enmity from neighbors and friends. To honor Wright, his clerks and spouse endowed a fellowship to bring public interest lawyers to inspire and teach law students. The first set of Skelly Wright Fellows was Marian Wright Edelman and Peter Edelman, longtime advocates of the poor; Bright was appointed the next Fellow. A rigorous pedagogy in the classroom and true stories of legal injustice in the Deep South made Bright an instant sensation. Through his teaching and mentoring, he sought to inspire the next generation of students to pursue social justice as a calling and if they did not, to at least devote a portion of their legal careers to defending poor people who desperately needed legal representation.

Graduating students asked him to give that year’s commencement address. After giving an electrifying send-off, Bright hustled down to New York City to appear on William F. Buckley’s television show, Firing Line. There, Bright reunited with Bryan Stevenson, who had recently left SCHR to establish a program that would offer legal services to people on Alabama’s death row, a precursor to Equal Justice Initiative. Stevenson himself was once a law student seeking a purpose. An internship spent at SCHR gave him a cause and his first job after graduation.

The two men didn’t rehearse what they would say in advance. But their televised reunion allowed them to lay down pragmatic arguments drawn from their courtroom experiences and build on each other’s rhetorical contributions. The occasion “was a rare prime time opportunity to talk about the death penalty,” Stevenson later recalled to me in an interview. “We wanted to talk about the human face of the death penalty, the day-to-day racism, the abuse of power.” The approach from this long-forgotten moment would foreshadow the gritty tactics utilized by advocates around the country to incrementally—and successfully—chip away at legal and moral support for capital punishment. In shining a light on deeper structural flaws in the criminal justice system, these arguments also laid the groundwork for others to pick up the mantle of legal change to tackle the unjust treatment of people charge with non-capital offenses.

The debate begins

On May 24, 1994, Michael Kinsley, former editor of The New Republic, kicked off the debate at Bard College. William F. Buckley, Jr., former New York City Mayor Ed Koch, Georgia Assistant Attorney General Susan Boleyn, and Walter Berns, a Georgetown professor, assembled to make the case in favor of capital punishment. The opposing case would be presented by Bright, Stevenson, Ira Glasser, Executive Director for the ACLU, and Leon Botstein, President of Bard College.

A liberal gadfly, Kinsley framed the issue cheekily: “One of the things that makes us special, at least, among the advanced democracies of the world, is the death penalty.” The ultimate penalty “was abolished long ago in all the countries of Europe” and recently in the former Soviet Union and South Africa, he observed, “but in the United States, the pace of execution only increases.” He directed attention to that year’s crime bill, which added “dozens of new death penalty offenses” and enjoyed “strong support of both parties in Congress and of President Clinton.” Introducing the speakers, Kinsey said, “If Mr. Buckley had his way, there would be capital punishment for blocking his limousine in traffic, or raising taxes, or even for being a Democrat.” About Koch, Kinsley said that as Mayor, “he was unable to send anyone to death, but I suspect he would have liked to.”

This was brilliant political theater, but more important, it captured the swirling politics on crime and justice. Buckley set the tone for the pro-death penalty side, doubling down on “America’s enthusiasm for execution.” The people favored capital punishment, he said, and in a democracy, the majority’s preferences should have its way. Thus, Buckley’s scorn was reserved not for the bloodthirsty, but for the defense lawyers and activists responsible for “fiercely frustrat[ing]” retributivist sentiment. In doing so, he tried to turn liberals’ penchant for fairness on its head. Buckley was thrilled that Congress was considering bills to restrict a prisoner’s access to the courts, saying that death penalty opponents were being “hoist by their own petard” for making “effective justice impossible.” He derided defense lawyers’ efforts to keep their clients alive as “a waste of time,” resulting in “the frustration of the democratic process.” In other words, for someone like Buckley, court-created and enforced procedural rules advanced by do-gooders were anti-democratic. Buckley believed that the average citizen wanted to see more executions rather than fewer.

As captain of the opposition, the ACLU’s Glasser went next. He made two points: there was no proof that the death penalty deterred homicide or lowered crime rates; and it was morally impossible to distinguish between the vast majority of killers who were spared the death penalty and the 2% who were sentenced to die.

Koch, who exemplified the political consensus of the day, even in New York City, similarly argued, “We are fighting a war against crime and I’m willing to take on that obligation, even though someone innocent might be executed.” America was under siege, he asserted: “people can’t use the streets, the subways. Throughout the country they are petrified.”

Susan Boleyn, an 18-year veteran of Georgia’s death penalty unit, then spoke. Boleyn had gone against Bright and Stevenson on a number of cases, and she relished the chance to take them on again. “As far as I’m concerned,” she said, “the debate today should be over whether the death penalty we have is appropriately administered.” Boleyn took umbrage at the “presumption” that Southern states were still racist. “I’d like to tell you that it’s not 1950 anymore.”

But shifting the terms of the debate from universal moral arguments or majoritarian ones to how the death penalty was actually implemented opened the door to fresh arguments. It allowed opponents to respond by teaching viewers why so many poor people and racial minorities wound up on death row. Under the debate rules, Stevenson was given the chance to question Boleyn. “It’s not the 1950s,” Stevenson replied, but studies showed that if a defendant is black and the victim is white, “you’re 22 times more likely to get the death penalty.” Stevenson was referring to McCleskey v. Kemp, a 5-4 decision in which the Supreme Court rejected an equal protection claim by a death row prisoner. Confronted by stark racial disparities revealed in the Baldus Study of Georgia’s capital punishment practices, five justices found nothing wrong with the study. Nevertheless, they took the extraordinary step of insulating the legal system from structural racism allegations.

According to Stevenson, these racial disparities existed because white people were still mostly in charge of the justice system. “There are still no elected district attorneys who are black in the State of Georgia,” he observed. “What has changed between 1950 and 1994 that allows you to support or assert that the death penalty is being applied fairly now?”

Boleyn was not satisfied. She noted that there were more white people than black people on Georgia’s death row overall. “But how did that prove that race is not a factor?” Stevenson wondered. He presented a different figure: “The bottom line is that only 27% of the population of Georgia is black, yet 75% of the people that have been executed in that state are African American.” “Do you want an answer to your question, or are you wanting to tell me your statistics?” Boleyn sniffed. Stevenson shot back, “I want an honest answer.”

When it was his turn at the lectern, Bright hammered away with his own evidence. “Even though 65% of the victims of crimes are African Americans” in Georgia, “16 of the 18 executions, I’m talking about people who have been buried… have been cases with white victims,” Bright thundered. In doing so, he found a way to dramatize a central finding of the Baldus study in the McCleskey case the justices had ignored: prosecutors were much more interested in protecting white lives and white property.

Boleyn shook her head. “That does not show discrimination.” “It doesn’t? Is it a coincidence?” Bright’s face was etched in disbelief.

Boleyn gave the numbers an individualistic spin: “No. The fact is this is calling people accountable for the crimes they commit in particular circumstances.” It merely showed people were being held “accountable for the crimes they commit in particular circumstances.” She didn’t think patterns of enforcement were relevant, only individual situations.

But “why are only black people held accountable when they kill white people?” Bright wondered aloud. At that point, Bright had Boleyn back peddling. He pointed to fresh statistical evidence beyond the Baldus Study that the state could not be trusted to run murder trials fairly. “Do you think we can take into account that prosecutors in Georgia strike all the African Americans from juries?” he asked. “Have you read Horton v. Zant out of the 11th Circuit?” Bright asked. In that case handled by Bright and a cooperating attorney, federal judges overturned a black man’s death sentence because the prosecutor “used 94% of his jury strikes against black people” over the course of his career.

Bright stood up and approached the podium. “I do think that the issue before us is how the death penalty works in practice,” he began. “I practice in the death belt states of the South—those states with about 16% of our nation’s population, that are responsible for 90% of all the people who’ve been executed in this country. And the evidence is undeniable that the death penalty is a result of race, poverty, politics, and the passions of the moment.”

Beyond highlighting the role of prosecutorial discretion, which could be easily abused, he also emphasized structural conditions: how insufficient resources for the poor meant “we impose the death penalty not for committing the worst crime... We impose the death penalty for having the worst lawyer appointed to your case.” Applause broke out spontaneously. When it subsided, he went on to explain that indigent people are routinely appointed “lawyers that nobody up here, nobody on your side would have represent them in a minor traffic matter—lawyers that Mr. Buckley and Mr. Koch wouldn’t have drive their limousine.”

Bright offered illustrations from his own cases: “Judy Haney[’s] lawyer was so drunk he had to be sent to jail in the middle of a trial!” He said “there’s case after case like that” with people “represented by lawyers who are underpaid, who are incompetent, and who are doing this work because there’s nothing else they can do.” In just a few moments, Bright had crystallized a litany of structural complaints about the justice system.

Buckley interrupted Bright’s momentum. The two men now squared off. Though they both hailed from the South and had ties to Yale, they could not be more different. Buckley, born a Virginian, had been raised in Connecticut and retained an aristocratic air as he disdained the liberalism associated with his undergraduate institution. Bright, the Kentuckian who had never set foot on Yale’s campus until his death penalty work earned him entry to its hallowed halls, maintained his working-class sensibility. One man emphasized the need for social order; the other, the demands of equal justice.

“Do I understand, Professor Bright, that what you’re saying is that the better your lawyer, the better chance you have of getting the guilty guy out? If that’s correct, shouldn’t this be a campaign … to reduce the manipulations that the lawyers can work?”

Bright answered that “these are very complicated cases” and when Buckley needed help with his taxes “you get a tax lawyer to help you.” But poor people facing trial “don’t get to call up Skadden Arps.” Buckley shifted gears: If someone is guilty, “I don’t care about the composition of the jury.” But Bright exploited Buckley’s error. “There’s something to be said for the integrity of the system and the process.”

Buckley interjected: “You are a professor of law. Raise hell about bad lawyers.” Bright was quick with his retort: “That’s exactly what I do, Mr. Buckley, every day.” More laughter.

Although Bright was trying to improve the standards for lawyering through his teaching and advocacy, he also appreciated that to make any headway in improving legal services around the country required reaching citizens who for years had been told to think only about incapacitation and retribution over fairness and equality. As if he were addressing a national jury, Bright explained that deciding guilt or innocence was only the first step in a criminal case. After a conviction, “you get into questions about the person, their life, and background” to determine the appropriate punishment. He referred again to Haney, “who had been battered and abused by her husband for 15 years, and her children had been battered and abused.” None of that was presented because the lawyer was intoxicated, and “she’s waiting to be executed on Alabama’s death row right now.” He said that this “is the reality of the death penalty in this country.”

Finally, it came Buckley’s time to sit in the hot seat. Peppering him with questions, Bright sought to illustrate the fallible nature of human judgment in order to shake the retributivist’s confidence in even the question of guilt/innocence. He said that in the last year four people had been released from death row, “one Mr. Stevenson represented, who had been on there eight years.” Another had been on death row for 11 years before being exonerated.

Buckley tried to muddy the waters: “But you’re assuming they are innocent. I don’t necessarily assume they’re innocent.” Yet Bright held the line: “Well, they were proven to be innocent. Bryan’s client, for example, was at a fish fry when the murder took place in another county, Mr. Buckley. That’s as innocent as you can get.”

“The number of guilty people who get sprung wouldn’t fit in Madison Square Garden,” Buckley retorted testily. Bright pressed forward: “I’m talking about innocent people… if there had not been DNA technology, he would have been executed.”

Overconfident but underprepared to tackle legal details, Buckley’s gambit backfired. He was effective making quips. But his languid style had not shown lawyers to be used car salesmen. To the contrary, he allowed Bright’s side to illustrate that competent representation preserved the legitimacy of the justice system. If you were ever in serious trouble with the law, and everyone abandoned you, you’d want Bright or Stevenson to stand beside you.

The possibility of abolition

In the second hour, Bright reclaimed the podium. Proponents of capital punishment had their chance to pelt him with questions. Boleyn tried to bait him into saying that he believed nearly every lawyer out there was incompetent, but Bright avoided the gotcha-moment by returning to the structural conditions of indigent defense. “When lawyers are being paid in these cases an hourly rate that’s less than the overhead that it costs to keep their office open,” he observed. “You can’t get anybody to do those cases for that kind of money.” The audience was being exposed to the political economy of injustice. It was not every day that moral debate over punishment practices could delve deeply into the problems of discretion and judgment, geographic variations, and financing of public programs—yet still be riveting for listeners. “Next time you need a lawyer … try to hire a lawyer for $ 2 an hour,” Bright said, underscoring that in America the amount of money a person had still dictated the quality of justice he would likely receive.

Back and forth, the participants jockeyed for advantage. Tough-on-crime rhetoric, with its emphasis on victims’ rights and oversized fears of violence, remained dominant. And things would get worse before they got better with the enactment of the 1994 Crime Bill, which expanded use of the death penalty, incentivized longer sentences, and funded the construction of more prisons. On April 19, 1995, Timothy McVeigh would bomb a federal building in Oklahoma City. That act of terror would drive Americans’ support for capital punishment to its highest peaks in the modern period. It would take another two decades before citizens and elected officials began to actively reconsider the wisdom of War on Crime policies.

Support for capital punishment eventually returned to what it had been in the early 1970s. More citizens understand the flaws of the justice system. When the people of Virginia abolished the death penalty in 2021, for example, Governor Northam explained that “the system doesn’t work the same for everyone.” One of the sponsors of the bill said that the death penalty is “immoral, racially biased, ineffective, and costly.”

Back in the 1990s, foreseeing the possibility of abolition required enormous political imagination. So much work still had to be done. Even so, on that day in May Bright and Stevenson had accomplished their objective. “Anybody could talk about deterrence and retribution, and everyone could go home comfortably,” Stevenson reflected. But talking honestly about human error and asymmetrical resources “complicates how you situate yourself.” What had been revealed as “the ugly face of the death penalty” on national television proved to be an effective counter to “the theory of it.” Advocates for the poor and proponents of criminal justice reform would need the tenacity they displayed and the potent arguments they unleashed to advance the cause of human dignity.

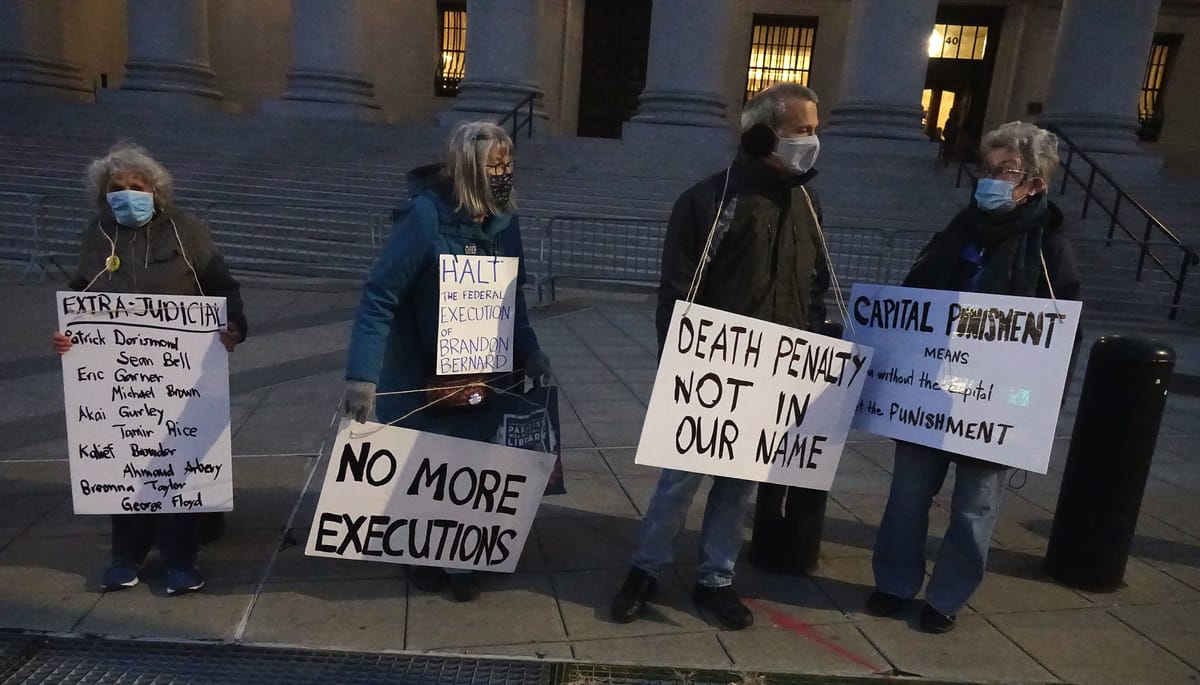

Featured image is Brandon Bernard Vigil, by Felton Davis