Against the Slave Power: the Fugitive Liberalism of Frederick Douglass

Douglass elaborated a political theory from his experiences as a slave, where institutions were directed against people like him. He had to become attuned to the differential character of law as it applied to slaves and other outlaws.

… we the people, the people, the PEOPLE—we, the people, do ordain and establish this Constitution. There we stand on the main foundation. [Sources of Danger to the Republic, 1867]

Frederick Douglass is the liberal mind for our antiliberal times.

The remarkable life story of Frederick Douglass—escaped slave, abolitionist newspaperman and orator, advisor to presidents, and statesman—tends to eclipse the man’s own ideas. But his star-spangled résumé also featured the fact that he was an innovative political philosopher. His autobiographies are barely disguised political treatises more than they are memoirs. He omits almost any reflection on his intimate relationships, and every story he relates is a parable for some philosophical idea. His vast corpus of writing included essays and speeches explicitly on the nature and justification of government, the derivation of rights, the limits of the Constitution and democracy, and the philosophy of reform.

Douglass was a liberal, though liberals have oddly tended to leave him on the shelf—a glance through any history of liberalism almost invariably fails to even mention Douglass. Douglass’s individualism, his appeals to natural rights, his cosmopolitanism, and his beliefs in self-betterment and social improvement through commerce and industry all fit a basic liberal outlook. But it’s hard to pin him down to anything narrower than that.

What is distinctive about the political philosophy of Douglass—what sets him apart from other liberals—is his fugitivity. Douglass had an ambivalent relationship with the law and a willingness to think and act outside established institutions. Like any good liberal, Douglass advocated the rule of law and stable representative institutions. Liberals are comfortable theorizing about political institutions and constructing mythical origin stories to justify those institutions. Douglass, by contrast, elaborated a political theory from his experiences as a slave, where institutions were directed against him and people like him. He had to become attuned to the differential character of law as it applied to slaves and other outlaws—those outside the law.

The institutional breakdown prior to the Civil War and the extraconstitutional cataclysm of the Civil War itself gave Douglass reason to think about how liberal values could be applied in a revolutionary context of institutions in flux. A keen awareness of the militarily defeated but socially and politically unbroken spirit of slavery gave Douglass a no-bullshit attitude toward the fragility of liberal institutions. Douglass was attuned to how inequalities of wealth and political power and the ever-adaptive spirit of slavery represented ongoing threats to the republic and the flesh and blood people it comprised.

A fugitive liberal

Douglass embodied this fugitive rebelliousness against the established authority from his earliest memories as a slave boy. He recounts the “first decidedly anti-slavery lecture” he ever heard—Hugh Auld explaining to his wife Sophia the danger of teaching young Fred how to read. It would “unfit him to be a slave.” Douglass resolved to learn at all costs. This commitment to unfitting himself to slavery would extend to teaching his fellow slaves to read, an objective he would clandestinely pursue for the rest of his tenure in bondage.

Reading and teaching may feel like small stakes. The slave drivers would disagree, but Douglass’s fugitive philosophy would develop further when he found himself “pinched with hunger.” Stealing food from his master was justified easily enough as simply moving the master’s property from one bin to another, since his belly also belonged to Master Thomas. Douglass found that slaves are justified in stealing from society at large, and not just the necessaries of life, but gold and valuables.

It was necessary that the right to steal from others should be established; and this could only rest upon a wider range of generalization than that which supposed the right to steal from my master. It was some time before I arrived at this clear right. To give some idea of my train of reasoning, I will state the case as I laid it out in my mind. 'I am,' I thought, 'not only the slave of Master Thomas, but I am the slave of society at large. Society at large has bound itself, in form and in fact, to assist Master Thomas in robbing me of my rightful liberty, and of the just reward of my labor; therefore, whatever rights I have against Master Thomas I have equally against those confederated with him in robbing me of liberty. As society has marked me out as privileged plunder, on the principle of self-preservation, I am justified in plundering in turn. Since each slave belongs to all, all must therefore belong to each.' [Life and Times of Frederick Douglass (LTFD), 1892]

Emphases mine. Douglass does not dispassionately derive his conclusions from first premises. He seeks out this reasoning because necessity—the pinch of hunger—requires that he steal food. Yet he must justify his actions, both to himself and to an imagined other, and eventually to his readers. The right derived from his need is clear. Moreover, because it is not the singular slaveholder, but an ideology and elaborate political economy of the slave power that oppresses the slave, transgressive actions against the system of slave power itself and those individuals enabling and enacting the slave power.

This parable captures a recurring theme of Douglass’s fugitive liberalism. Transgressive actions are morally authorized and sometimes even demanded by the manifest needs of people for “self-preservation,” in order to survive. But we must justify these actions and prepare some path to lawful relations between free and equal persons after the transgression.

Douglass continues,

The morality of free society could have no application to slave society. Slaveholders made it almost impossible for the slave to commit any crime, known either to the laws of God or to the laws of man. If he stole, he but took his own; if he killed his master, he only imitated the heroes of the revolution. Slaveholders I held to be individually and collectively responsible for all the evils which grew out of the horrid relation, and I believed they would be so held in the sight of God. [LTFD, 1892]

Douglass occupies a double position. Those who take decisive action against the slave power are like unto the heroes of the revolution. At the same time, this is a perversion of the morality of the free society. The slave power necessitates actions unbefitting free people.

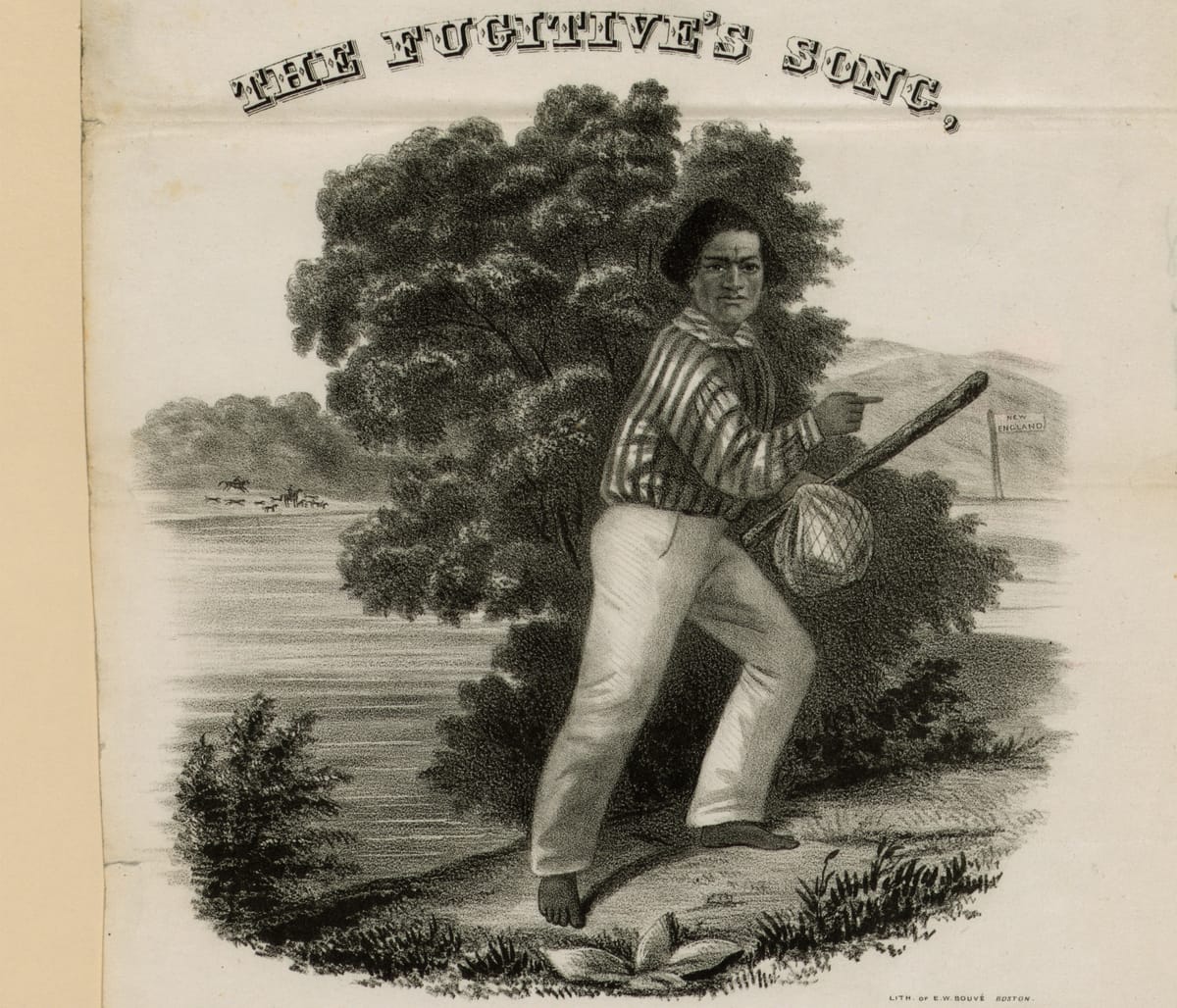

Douglass enacted these values as a fugitive ex-slave. Like many escaped slaves, Douglass lied and forged official documents in order to make his escape to the North, with the crucial assistance of Anna Murray, a free Black woman who would provide his travel fare and later marry Douglass. It’s worth pausing to emphasize the inherent fugitivity of the escaped slave. There were no legal pathways to the North, even in principle—no queue, no forms, no fees. Escaping from slavery was pure lawbreaking.

Once free in the North, Douglass had to live in anonymity or risk being kidnapped by slave catchers and returned to bondage in the South, against which he would have no legal recourse. When Douglass chose to reveal his identity in 1845 by publishing his Narrative of the Life of a Slave, he fled to the British Isles, where he would live in exile for 22 months and only return when some of his friends had pooled enough money to purchase his freedom from his former owner. The life of a freed slave was one of extreme legal precarity.

Just as he wanted to share the liberating power of the written word with fellow slaves, Douglass wanted to aid the escape of as many enslaved persons as possible and so he became involved in the Underground Railroad. On at least one occasion, this led Douglass to sheltering fugitive slaves who had killed agents of the state in their flight. After the Fugitive Slave Act of 1850, Douglass advocated deadly resistance against those who were authorized by the Act to capture and abscond with escaped slaves. “The only way to make the Fugitive Slave Law a dead letter is to make half a dozen or more dead kidnappers.”

Douglass was a friend and confidante of John Brown, who would lead the raid on the federal armory at Harpers Ferry in 1859 that ultimately sparked the Civil War. Douglass refused to join Brown on the raid, and advised against its execution, but Douglass also kept Brown’s confidence, was forced to flee the country for his complicity, and would for the rest of his life sing Brown’s praises as an American hero.

This brief recounting of these events of Douglass’s life shows Douglass was no stranger to violence, including violent resistance against the state. But Douglass would offer his radical counsel to the state as well as against it. Douglass criticized Lincoln for placating the South and demanded the emancipation and arming of the enslaved population to fight against the slavers. Though a fierce critic of Lincoln during the early, reticent stages of the Northern campaign, Douglass would go on to defend Lincoln’s wisdom. Notably, Douglass’s fugitive relation to the law could extend to those in positions of authority when they were willing and in a position to strike a blow against the slave power. Douglass exalts Lincoln for being willing to do what was necessary—in spite of strict adherence to norms and procedures—to save the republic.

We appealed, to be sure—we pointed out through our principles the right way—but we were powerless, and we saw no help till the man, Lincoln, appeared on the theater of action and extended his honest hand to save the republic. No; we owe nothing to our form of government for our preservation as a nation—nothing whatever—nothing to its checks, nor to its balances, nor to its wise division of powers and duties. It was an honest president backed up by intelligent and loyal people—men, high minded men that constitute the state, who regarded society as superior to its forms, the spirit as above the letter—men as more than country, and as superior to the Constitution. They resolved to save the country with the Constitution if they could, but at any rate to save the country. To this we owe our present safety as a nation. [Sources of Danger to the Republic, 1867]

Emphases mine. At the root of Douglass’s fugitive philosophy is his observation that, at the end of the day, it is up to the individual to act. Republican government cannot survive without moral individuals doing what is necessary to uphold republican principles. No constitution or system of government sustains itself by force of words or reason. It is always up to individuals to do the right thing. In a political crisis where rogue parties are determined to ignore norms and laws and resort to violence, the form of government and the delineated functions and powers of institutions may be powerless to repel them. In an extraconstitutional situation where the Constitution has already been ignored or overridden, the Constitution itself offers no guidance for returning to a constitutional context.

Douglass reminds us that the Constitution doesn’t exist for its own sake. The purpose of government, our laws, our Constitution, is to serve flesh and blood human beings. Lincoln and his allies sought to save the United States within the Constitution if at all possible, but they resolved to save the nation by going around the Constitution if necessary.

Lincoln and his allies were in the theater of action. They were the ones situated to act, to steer the mass of citizens and resources to oppose the threat facing the nation that was rent asunder. By “theater of action,” Douglass distinguishes Lincoln and his government from the millions of Americans who could express their values, vote one way or another, and engage in individual acts of humanity and resistance, but who ultimately were at the mercy of powers and events outside their control.

Finally, Douglass speaks of Lincoln’s “honest hand.” Lincoln may have had to seize extraconstitutional power to save the country, but that doesn’t mean anything goes. Douglass’s fugitivity is always liberal. It is always bound by the spirit of law and humanity, and only authorized when peaceful and legal options have failed. Resorting to violence or seizing power for vicious reasons must always be condemned.

The spirit of slavery

Douglass was thus not a fire-breathing radical by disposition. The radical measures he advocated always aimed at creating or returning to a state of freedom, equality, and social order. He resisted any temptation for revenge or violence beyond what was necessary for liberal order. In his famous conflict with the slavebreaker Edward Covey, Douglass tells his readers that he fought defensively, and avoided striking any crippling blows. In one of the greatest political disappointments of his late life—and what would be seen by later generations as the end of Reconstruction—the Supreme Court effectively nullified the Fourteenth Amendment and the Civil Rights Act of 1875. Though Douglass saw this as a calamity that left Black people in the United States naked and defenseless, he still saw the potential for peaceful reform, and resisted calling for violent action against the “autocratic” Supreme Court.

Liberals crave clear rules for when to “break glass in case of constitutional crisis,” but such crises are always novel, and by definition spread outside known political terrain. There be dragons. Douglass couldn’t offer hard and fast rules, but he offered a model of forbearance—resisting radical measures as long as possible—with constant appeal to constitutional principles, and an invitation to return to constitutional relations.

Throughout his autobiographies, Douglass humanizes whites and even slave-owners, first the neighborhood children who were too young to grasp why Douglass was different from them and was fated for slavery. Douglass had an evident affection for his mistress, Sophie Auld, who began teaching him how to read out of her good nature, before Hugh Auld imposed the spirit of slavery on their otherwise natural human relationship. Later in life, after the war, Douglass recounted visiting a now elderly Thomas Auld. Even this man, who had presumed to own Douglass and subject him to slavery, was given the benefit of Douglass’s orientation toward a future of peace and equality.

[N]ow that slavery was destroyed, and the slave and the master stood upon equal ground, I was not only willing to meet him, but was very glad to do so... He was to me no longer a slaveholder either in fact or in spirit, and I regarded him as I did myself, a victim of the circumstances of birth, education, law, and custom. [LTFD, 1892]

Douglass’s great enemy was not any person, but the system and spirit of slavery. Though slavery itself was destroyed by the Civil War, Douglass believed the spirit of slavery persisted, and would take generations to fully defeat. "Though the rebellion is dead, though slavery is dead, both the rebellion and slavery have left behind influences which will remain with us, it may be, for generations to come." This spirit of slavery is the systemic racism that critical race theorists and other racial justice activists have brought to our attention, the systematic and persistent social, economic, and political disadvantages thrust upon Black people in America. The slave power—the political faction that implicitly or explicitly acts to preserve systematic Black disadvantage and the domination of a white elite—persists to the present day.

The MAGA movement of Donald Trump represents the slave power in its most acute contemporary form. In the second part of this essay on fugitive liberalism, I will explore how Douglass’s ideas might be applied in our own time of antidemocratic authoritarianism, outlaw communities, and constitutional crisis.